This story is published in collaboration with Belt Magazine.

On a warm morning in July of 2020, FBI agents and local sheriff’s deputies converged on a farmhouse just outside the tiny town of Glenford in central Ohio. They led away a blue-eyed man wearing a gray Carhartt T-shirt and baggy jeans. He was heavy around the middle, clean-shaven, with closely shorn white hair. His name was Larry Householder, insurance man, gentleman farmer, and the powerful leader of a Republican supermajority in the Ohio House of Representatives.

Federal prosecutors brought Householder before a judge and laid out their findings. Their investigation suggested the politician had orchestrated a grand conspiracy in which three electric utilities — FirstEnergy, its former subsidiary Energy Harbor, and American Electric Power — gave Householder a $60 million slush fund to help get like-minded politicians into the Ohio legislature. In exchange, Householder helped steer billions of dollars in subsidies their way.

As Householder left the courthouse, his head bowed, the yellow straps of an N95 mask cutting into the back of his neck, a gaggle of reporters thrust microphones toward his face.

“Do you have anything to say to the people?” one journalist asked.

“Not at this time,” Householder mumbled.

It was a rare moment of silence for Householder. He was known as a talker, when knocking on doors in a camouflage hat and bulky sweatshirt while campaigning, or presiding in a tailored blue suit from the speaker’s thronelike marble dais in the Ohio House Chamber. You couldn’t shut the guy up.

Over the course of three years, Householder had taken money from energy companies and transformed it into power. (Most of it, anyway. He kept some for himself, including $100,000 to pay for his house in Florida, according to an indictment filed by the U.S. Department of Justice.) The money built an army of state representatives that elevated him to speaker of the statehouse and supported his legislative agenda. It also paved the way for the passage of a law in 2019, House Bill 6, “widely recognized as the worst energy policy in the country,” according to Leah Stokes, an environmental political scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

House Bill 6 nearly halved the renewable power that utilities were required to buy, eliminated energy efficiency laws, handed a billion dollars to the state’s two nuclear power plants, and spent even more money to keep coal plants burning. A recent report from Gabel Associates, an energy consulting firm, suggests the law will cost Ohioans $2 billion in excess utility bills and $7 billion in health care costs stemming from pollution over nine years.

When both opponents and backers of House Bill 6 are asked about this scandal, they tend to talk about nuclear power. To opponents, it was a “nuclear bailout.” To backers, it was a sort of state-level “Clean Air Act,” meant to keep Ohio’s two nuclear plants from closing, thereby preserving the state’s largest source of zero-emissions energy. But nuclear power was mostly a red herring that utilities used to distract from the real thrust of the law: keeping obsolete coal plants and coal mines profitable.

“House Bill 6 was really a coal bailout wrapped in a clean energy and nuclear argument,” said Stokes, who wrote about the episode in her book, Short Circuiting Energy Policy.

Over the course of four years, FBI investigators tapped phones, recruited informants, and traced the movement of money between Householder and utilities. Grist obtained the FBI’s findings in court documents. Along with interviews and accounts published by Ohio newspapers, we’ve used this information ahead of the start of Householder’s trial to build out a narrative of the brazen attempt by utilities to buy legislation. The story has all the details of a potboiler — hidden recorders, damning conversations, a suicide, bribes, dirty politicians, and corrupt companies that financed it all. But it also presents an unusually vivid picture of the larger trend of fossil fuel companies using every trick they can to keep milking money from their investments in dirty energy — tiptoeing right up to legal boundaries and sometimes stepping over them.

Ever since the 1870s, when Standard Oil monopolized the petroleum industry, big companies dealing in fossil fuels have tried to bend the political process to their will. Now, there’s more temptation than ever: State legislatures are increasing regulation of dirty fuels in the interest of taking on climate change, while falling prices for wind and solar undercut their market. The pressure is greatest on utilities that have recently sunk millions into dirty power plants. “For regulated utilities, profits are determined by how much political influence you wield,” said Dave Anderson, communications and policy manager of the nonprofit watchdog organization Energy and Policy Institute, which has been digging up the details of this case for years. “It’s really just all about the money and driving as much profit as they can for their shareholders.”

As it becomes clear that clean energy poses an existential threat to fossil fuels, utilities that bet on the insignificance of renewables are launching counterattacks to maintain their dwindling turf.

“There’s a clear pattern,” Stokes said. “Utilities are rolling back climate policy, and they are charging ratepayers to do it.”

In 2008, Ohio passed its first renewable energy law, mandating the construction of wind turbines and solar panels while creating programs to help residents and businesses insulate their homes and upgrade their appliances. Few saw any reason to oppose the measure — it came after a parade of states passed their own renewable electricity standards, beginning in the late 1990s. And both conservatives and liberals liked the idea of homegrown clean energy creating jobs and protecting the environment. In Ohio, the bill passed both houses with nearly unanimous support. But then the legislation started working. Turbines and solar panels sprouted, producing electricity that crowded out the energy from old power plants, cutting into utility profits.

“You saw the utilities and the fossil fuel industry catching wind of how quickly they could lose their stranglehold on the energy system,” said Anderson.

So Ohio’s fossil fuel industry, represented by utilities like Akron-based FirstEnergy and coal giant Murray Energy, began flooding the statehouse with money. Bill Seitz, a Republican state senator, voted for the clean energy bill in 2008. But around the same time, energy corporations donated $120,000 to his reelection campaign. He began working closely with them to roll back the law — and he wasn’t the only one. In 2014, the Ohio legislature passed a bill, sponsored by Seitz, gutting the renewable mandate. It threw red tape at wind energy projects, with a budget rider requiring bigger buffer zones around turbines than the state requires for fracking or coal mining.

Two years later, the utility FirstEnergy, one of the largest investor-owned utilities in America, took it a step further, emboldened by its recent legislative victory.

FirstEnergy was struggling. The utility’s power plant-owning subsidiary — FirstEnergy Solutions (later renamed Energy Harbor) — was deep in debt, and its old coal and nuclear plants were no longer providing reliable profits as renewables and cheap natural gas brought down the price of electricity. Executives needed cash to restructure that debt, and if they could get the public to provide it, they would be legends. But every bailout they’d tried to engineer had died in the legislature, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission had shot down an agreement that would have subsidized its nuclear and coal plants.

So FirstEnergy shifted its pitch, claiming its two nuclear plants were in danger of closing permanently. Other states were starting to pay nuclear plants extra for producing carbon-free electricity, and if Ohio failed to do the same, or provide some other sort of “legislative solution,” the company warned, the plants would close. Ohioans risked losing their $10 billion investment in nuclear power, the utility argued, along with thousands of jobs and 15 percent of the state’s electricity generation.

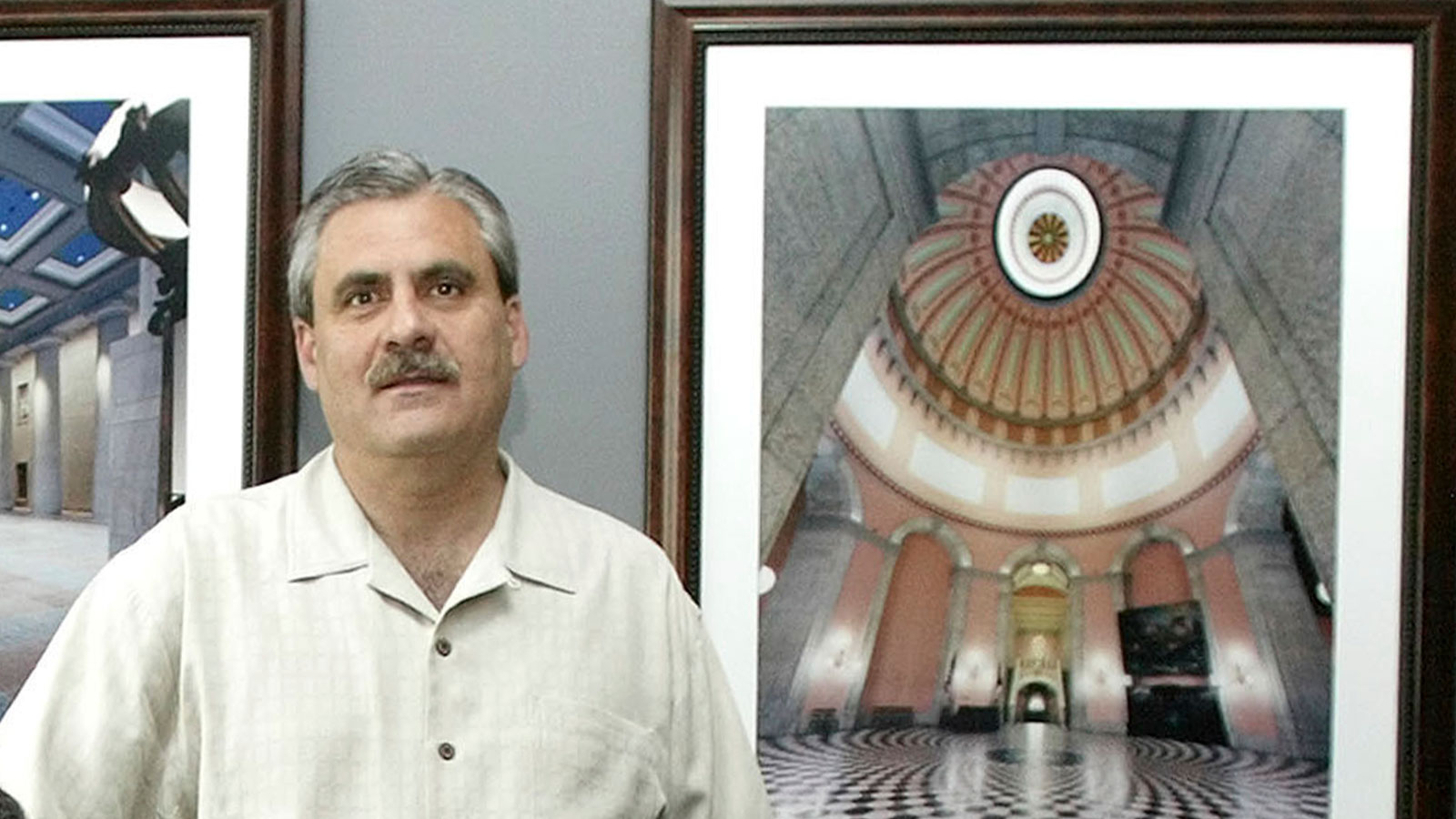

Around this same time, back in the small town of Glenford, Larry Householder was formulating his own comeback story. He represented central Ohio, what used to be coal country before the mines closed. A decade earlier, Householder had stepped down from his position as Ohio Speaker of the House and left politics after the media reported that the FBI was investigating corruption allegations against him. But nothing came of those charges, and in October 2016 he and his aide, Jeff Longstreth, mapped out an ambitious strategy: Not only would Householder run for office again, but he would also recruit candidates all over the state and provide the money to help them win their campaigns. That way he could walk into the House not as a single representative, but as the leader of a gang.

The timing was perfect. FirstEnergy and its subsidiaries needed a rainmaker in the legislature to secure a bailout, and Larry Householder needed a deep-pocketed patron.

Householder made a triumphant return to the statehouse, winning his assembly race in November 2016. A few months later, FirstEnergy began wiring hundreds of thousands of dollars to a “dark money” organization called Generation Now that Householder’s team set up in Delaware. It was just one of a constellation of front groups that sprung up to lobby for a utility bailout. The technical term for a dark money group is a 501(c)(4), a form of nonprofit that can spend money in politics without revealing anything about where that money comes from. As another member of Householder’s team, Neil Clark, a lobbyist who liked to call himself the “Prince of Darkness,” said in a conversation that investigators covertly recorded: “It’s a secret, a (c)(4) is secret. Nobody knows the money goes into the speaker’s account — it is controlled by his people, one of his people, and it’s not recorded.”

In the lead-up to the 2018 elections, FirstEnergy wired about $2 million to Householder’s dark money accounts, which then went to pay anywhere from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands of dollars for approximately 21 campaigns around the state. Most of these candidates won their elections. Every single one of them voted to make Householder the Ohio Speaker of the House. After a decade away, he was back in power — and this time he had a band of loyal supporters behind him.

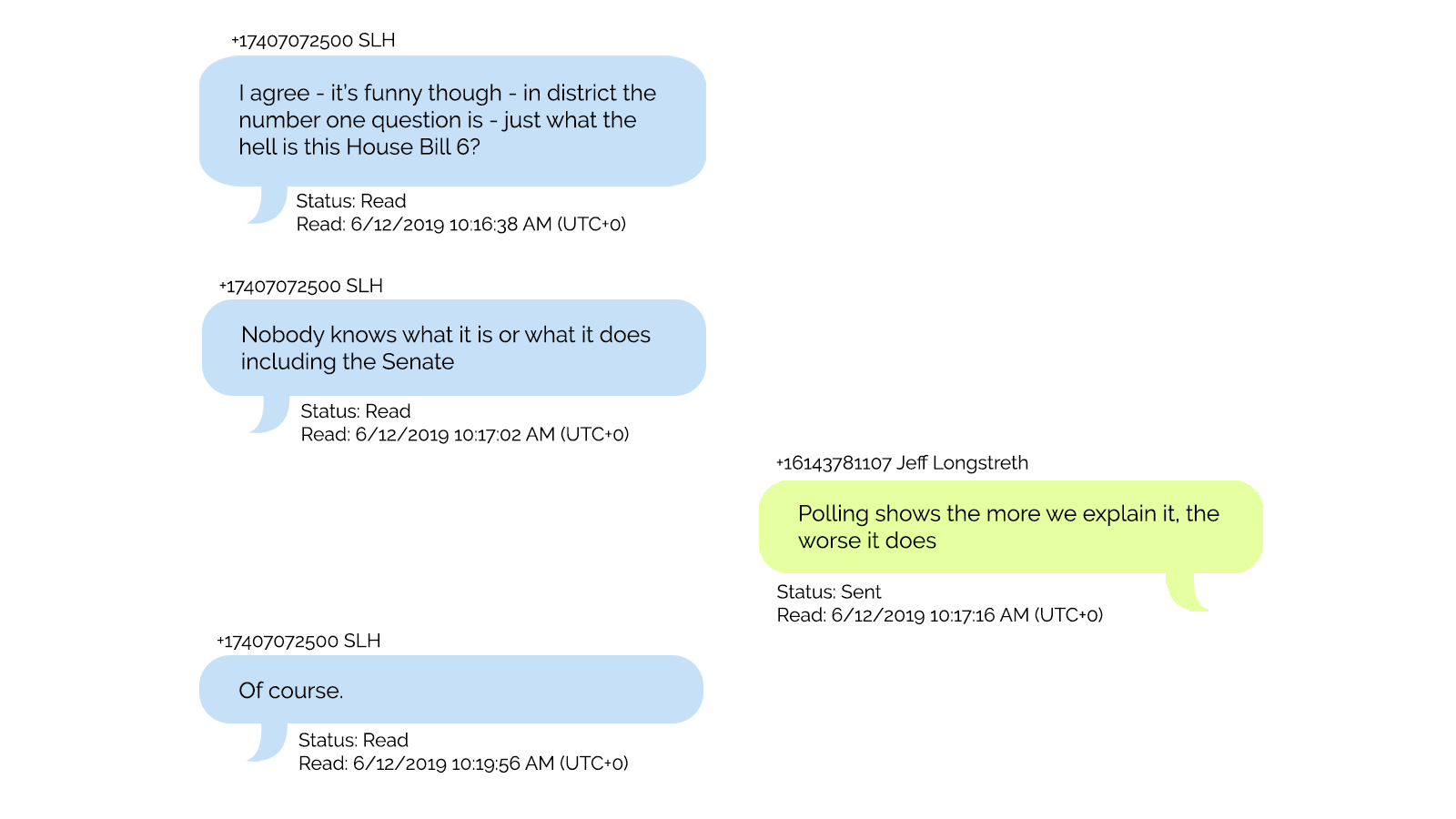

Householder took possession of the speaker’s podium in January 2019. A majority of House Democrats backed him after he offered them a big increase in public transit funding, a say in the budget process, and a promise that he would protect union rights and health care for the poor. On April 12, Householder unveiled the legislation he’d crafted to uphold his end of the deal with the utilities: House Bill 6. It would clean the air, he said. It would do away with the mandates for solar and wind, while giving “incentives” to existing zero-carbon power sources — that is, nuclear. It would etherize what was left of the 2008 renewable portfolio standard, eliminate the energy efficiency rules, and bind wind energy in red tape. At the same time, it would provide funding for a few token solar farms while handing over a billion dollars to energy companies, ostensibly for nuclear power. “We are trying to go from the hammer of the mandates, do away with the mandates, and instead provide a carrot,” Householder told reporters in a government conference room as he gestured at a whiteboard full of talking points.

Next Householder began gathering votes. Clark, the self-styled “Prince of Darkness” lobbyist, warned lawmakers that Householder had gone “to war” for the utilities with House Bill 6, twisting arms and calling in favors. “I have never experienced such pressure for any other bill,” one member of the Ohio House of Representatives wrote to another in a text that the FBI turned over to journalists after a public records request.

Householder’s team and the utilities also channeled a firehose of money at the issue. Generation Now and the other dark money groups spent over $16 million on mailers and television ads urging Ohioans to call their senators and representatives and ask them to vote for House Bill 6. One ad, featuring a power station worker, aired so frequently that even Householder complained in a text message that he was getting tired of seeing “that poor sumbitch drive that pickup truck down the road and cry about losing his job.” Less than two months after Householder introduced the bill, HB6 cleared in the Ohio House in late May. All but two of the candidates from team Householder ended up voting for the bill. It passed the Senate July 23 and Republican Governor Mike DeWine signed it into law the same day.

Citizens groups promptly organized a ballot campaign to repeal the law. “None of the arguments for House Bill 6 hold water except that this is policy driven entirely by a single larger donor,” Kent Smith, a Democratic state representative from east Cleveland, said.

In a memoir recounting his version of events, Clark wrote that the polling showed just a third of the public supported the new law. If petitioners gathered enough signatures to allow the public to vote on it, Householder and his team knew there was a solid chance that residents would reject House Bill 6. It was at this point they began to resort to more heavy-handed measures.

Householder’s crew approached signature gatherers across the state and offered them $2,500 and a one-way ticket home if they’d stop doing their work. (Many came from out of state, hired by Ohio activists to do the legwork to repeal HB6.) In a recording made by an FBI informant wearing a wire at a dinner party with Householder, Clark describes the plan: “We have to go out on the corners and buy out their people every day … If we knock off 25 people collecting signatures, it virtually wipes them out in the next 20 days; this ends the whole fucking thing.”

“Really the dirtiest thing was the effort to kill the petition drive,” said David DeVillers, the former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Ohio who oversaw the case for the FBI. “They were actually buying off companies that do petitions, to do nothing. And they were offering money and plane tickets to people on the ground who were getting petitions signed.”

To take it a step further, Householder’s team paid over $23 million for an advertising campaign warning that “the Chinese government is quietly invading our American electrical grid” and “coming for our energy jobs.” They followed up with a mailer telling residents that if they signed the petition, they’d be giving their “personal information to the Chinese government.” Of course, China had nothing to do with the effort to stop House Bill 6: The editorial board of the Cleveland Plain Dealer noted that the claims were spurious and called it “the sleaziest scare ad in recent memory.”

Federal investigators claim that Householder and his team went so far as to try to infiltrate the citizen campaign seeking to overturn House Bill 6 by bribing one of its employees, Tyler Fehrman.

In 2019, Fehrman, a Republican consultant, was in debt and out of work. That’s when citizens groups approached him, interested in tapping his GOP knowledge to help overturn HB6. In an interview with the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Fehrman said he asked his friend Matt Borges, a former state chairman of the Republican Party who had begun helping Householder with House Bill 6, for advice. Borges told him to take the job, Fehrman said.

Borges then asked Fehrman to meet him at Starbucks in Columbus. When they sat down outside, Fehrman said Borges attempted to bribe him to become a mole.

“‘Dude, I don’t have a mortgage anymore,’” Fehrman recalled Borges saying, according to the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “‘Like, I’m so taken care of. And we could do the same for you.’” At another meeting a few days later, Borges handed Fehrman a check for $15,000, according to FBI investigators.

Fehrman, who became an FBI informant, declined to talk to Grist, explaining that he needed to wait until he appears in court to tell his full story.

When Grist asked Borges for his account of the interaction, he didn’t equivocate: “Absolutely not. A hundred percent no. No, that’s not even — no! No,” he said.

Borges, a salt-and-pepper-stubbled lobbyist, acknowledged that he’d asked Fehrman how many signatures the campaign had gathered. But there’s nothing wrong with asking, he said.

“I can never and will never try to suggest that I wasn’t asking Tyler for information,” Borges said. “I was. I mean, it’s on tape, I couldn’t deny that. What I will never ever concede is that I was asking him for information that he was not allowed to give me.” Borges also said the check he handed Fehrman was to organize a party for former Ohio Supreme Court Justice Judi French — not for information on the repeal movement.

Fehrman never provided the numbers, but soon enough, Householder’s operatives could see that they’d won. The ballot measure effort failed to get enough signatures by October 22, 2019, the cut-off date for a referendum, and the law went into effect. If anyone at FirstEnergy popped open a bottle of champagne, however, they were celebrating too soon: FBI agents had infiltrated their inner circle.

In July 2020, law enforcement officers arrested Householder, Clark, Borges, Longstreth, and Juan Cespedes, a lobbyist for FirstEnergy. Authorities took away their passports, then released them to await trial from home. Those arrests marked the end of the undercover investigation but the beginning of a much more sweeping probe, DeVillers said. Once investigators had shown their hand, they were free to begin interviewing witnesses, cutting plea deals, and asking for documents.

The FBI then raided the Columbus townhouse of Sam Randazzo. Earlier that year, Ohio Governor DeWine had picked Randazzo, a lawyer who had earned millions as a consultant to FirstEnergy since 2010, to be the head of the state’s Public Utility Commission. (Though he hasn’t been charged, DeWine himself received more than $1.2 million dollars from utilities and their dark money groups for his election campaign in 2017.) When House Bill 6 passed, FirstEnergy CEO Chuck Jones, sent Randazzo a picture of Mount Rushmore with their heads, along with the faces of Wayne Boich — a coal scion who contributed money to Householder’s dark money groups — and another utility executive, photoshopped over Washington, Lincoln, and the other dead presidents. The caption in capital letters: “HB 6 FUCK ANYBODY WHO AINT US.”

In a legal agreement with federal prosecutors, FirstEnergy admitted it had paid a bribe of over $4 million to Randazzo shortly before his appointment as head of the Public Utility Commission. In exchange, Randazzo worked to fix the details of the new law so that utilities like FirstEnergy could collect more money from ratepayers.

“There’s been a pretty sweeping blizzard of subpoenas in Ohio, which suggests that a lot of people could go to jail before this is over,” said Anderson of Energy Policy.

Last March, a bicyclist found Clark’s body on a lonely road near his Florida vacation home. He died of gunshot to the head, according to a medical examiner, who concluded that it was a suicide. In his memoir, published posthumously, Clark wrote of the pain his family endured because his father was a mafia gunslinger who spent most of Clark’s childhood in prison. When FBI agents told him he would have to plead guilty to a felony, he stormed out of the meeting.

“One family member in prison was enough for me,” he wrote.

The legal case, stalled by the pandemic, will pick up again soon. A judge has made February 1 the final deadline for filing motions before the trial, clearing the way for a court date.

Longstreth and Cespedes have already pleaded guilty, while Borges and Householder have maintained their innocence. In 2020, Householder won another term in office, just months after FBI agents and local sheriff’s deputies arrested him at his home in Glenford. He ran unopposed. His office did not respond to Grist’s requests for comment. But he defended himself at length last June, when Ohio state legislators finally decided the evidence of wrongdoing was overwhelming and expelled him from the House of Representatives.

Householder appeared before the committee considering his expulsion in a navy pinstripe suit and a red tie. For half an hour he read from prepared statements, frequently breaking into impromptu asides. He joked and bounced on the balls of his feet. He told the room that kicking him out of office would amount to ignoring the will of the people who voted him in.

“I come from a community that is — to say downtrodden probably is an understatement,” Householder explained, growing grave. “We are a community that was a coal mining community and farming community that lost their coal mines. And things went upside down fast, and that’s what propelled me into politics in the first place.”

“They got a lot of faith in us,” he swallowed and nodded stiffly. “They should.”

The committee asked their questions, but none revealed anything new. Householder became mildly incredulous.

“I fully intend to walk into a courtroom in Cincinnati and walk out a free man and innocent,” he said.

Near the end of the hearing, however, Rick Carfagna, a Republican representative from central Ohio, asked a question that snapped the enormity of charges against Householder into focus. What about the hundreds of thousands of dollars that Householder had taken from the dark money slush fund for personal use, Cafagna queried. Even if Householder had been on the level and planning on publicly reporting the money as a gift, he asked: “How do you justify to the people in this room, to people on this committee, and to your constituents back home, accepting a gift of that magnitude for your personal expenses?”

Before Householder could speak, his attorney, Mark Marein, slipped up behind him. “I am advising him not to respond to that question,” he said. Householder shut his mouth.

Attorneys for Randazzo and Longstreth also declined to comment for this story. In a statement, a representative of FirstEnergy wrote that it has paused all political contributions and is taking “decisive actions to address recent challenges, rebuild trust with its stakeholders, and position the Company for long-term success.”

House Bill 6 remains in effect, but it has shed the facade of being a nuclear bailout. When lawmakers were debating the law, environmental policy wonks and journalists were skeptical that the nuclear plants really needed saving. There’s evidence they were right: As lawsuits loomed, Energy Harbor opted to decline the nuclear bailout and announced that its plants would not need to close after all. Howard Learner, president of the Environmental Law and Policy Center, suggested that the utility was telling at least a partial truth about the plants: When it filed for bankruptcy in 2018, the plants were unprofitable, but it was the bankruptcy process of restructuring debt and renegotiating union contracts that led to their profitability, not a bailout.

In March, Governor DeWine signed a new law that rolled back the nuclear subsidies, while leaving its other elements in place. The bill that Housholder shepherded into law three years ago forces Ohioans to fork over $200,000 a day to buoy ailing coal plants — Stokes estimates the total coal subsidies could come to $1.7 billion. Most Ohio Republicans favor keeping those elements of the law, Anderson said, despite the clear evidence that it was created through bribery and fraud.

As outlandish as this story might seem, utility and policy experts say it’s part of a trend. After a federal investigation in Illinois, the utility Commonwealth Edison admitted in 2020 that it had bribed the state’s Speaker of the House, arranging jobs, subcontracts, and monetary payments for the politician. An executive from the former SCANA Corporation pled guilty to defrauding ratepayers in an attempt to get an expensive new nuclear plant built in South Carolina. The power company Arizona Public Service has used millions in dark money to get friendly members elected to a commission that sets electricity rates. And many other states have passed coal bailouts under pressure from utilities and dark money groups, though in most cases there’s not solid evidence that lobbying crossed legal lines.

“Unfortunately the scandal is not an isolated incident,” Learner said. The growth in renewable energy is utterly transforming the power industry, he explained, and it only makes sense that some companies might fail to adapt, in the same way that the once mighty Blockbuster failed to adapt to the innovation of streaming video. “And if Blockbuster had decided it’s going to mount a battle in the Ohio legislature to stop streaming services from coming to market, it would have had to spend its own money. It didn’t have ratepayer money sloshing around to pay for it.”

But unlike video rental stores, utilities usually don’t just fold and go out of business. As regulated monopolies, they can stay alive and cling to an obsolete energy source if they know how to massage the right politicians. “The sad reality is that utility incumbents hold off competition and technological innovation through corruption of the legislative process when their merit case is weak,” Learner said. “If we want clean renewable energy, we need clean government.”

The reality, however, is that these scandals are likely to continue, Learner said, until people start going to jail.

*Correction: This story originally misidentified when FirstEnergy paid Sam Randazzo a bribe. It happened before his appointment to the Public Utility Commission.