The novel coronavirus is not only infecting people around the world, it’s infecting the global economy. As you read this, likely from the safety of your home, more restaurants and other small businesses are shuttering. States around the U.S. report that hundreds of thousands are filing for unemployment insurance. The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis predicts the unemployment rate could skyrocket to 30 percent by the end of the second quarter, which ends next week. That’s 5 percentage points higher than it was in 1933, during the depths of the Great Depression. Yes, it’s on a course that’s really that bad.

Congress is working on putting together a massive stimulus package to ward off the worst. An attempt to pass one with a $1.8 trillion price tag failed Sunday in the Senate because Democrats opposed what they called a “slush fund” of $500 billion worth of loans that would be meted out at the Treasury Department’s discretion. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts tweeted that Trump would direct the money “to boost favored companies and corporate executives.” (Democrats blocked another attempt to move a stimulus forward on Monday, but according to The Washington Post, senators on both sides seemed upbeat that evening that they would soon reach a deal.)

Which got us at Grist thinking. The money the government is about to inject into the economy is obviously needed to soften the blow from the COVID-19 outbreak. But it also gives us an opportunity to get ahead of another slower-moving emergency: climate change.

“Economic and financial experts are gravely concerned that the next economic crisis looming behind this one will be caused by climate change,” said Senator Sheldon Whitehouse from Rhode Island, in a statement to Grist. “While shoring up the economy from the coronavirus fallout, it’s responsible to address that future crisis, and help create millions of good-paying jobs in the clean energy sector while we’re at it.”

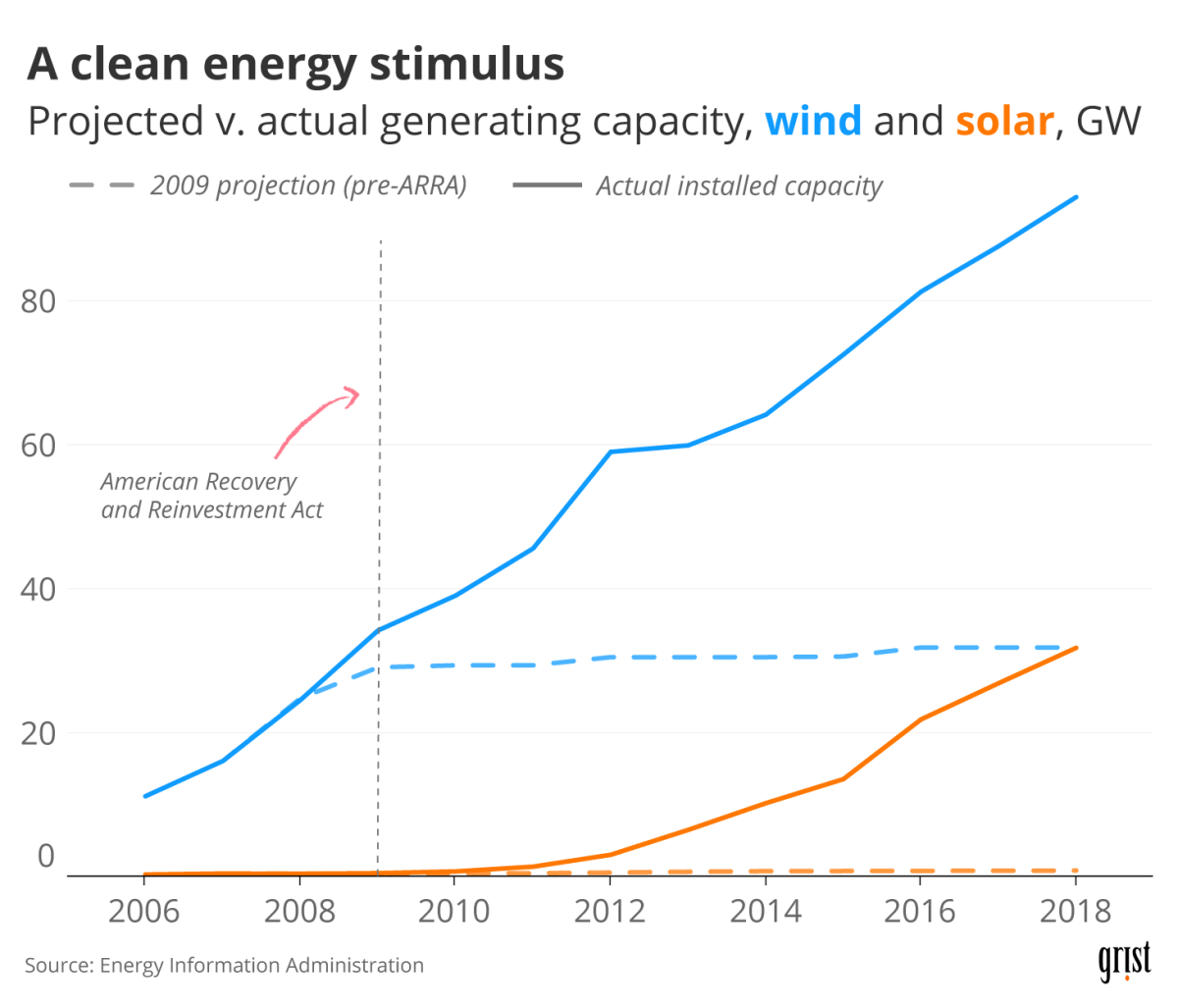

This isn’t just wishful thinking on the part of a known climate hawk. In 2009, during the Great Recession, President Barack Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a roughly $800 billion stimulus package. A portion of that — $90 billion — went toward clean energy projects. The impact, according to a 2016 report on those investments, was huge: “Solar electricity generation has increased over 30‐fold since 2008. Wind generation has increased over three‐fold since 2008.”

Clayton Aldern / Grist

Whitehouse himself is pushing for binding emission-reductions targets, as well as for investing in innovation to help green commercial and cargo air travel, including forcing airlines to buy offsets for their massive carbon footprints. Those are a sample of what climate and clean-energy advocates dream of stuffing into one of the multiple recovery packages likely required to recover from the devastating fallout from the coronavirus pandemic.

Grist reached out to experts from the fields of finance, policy, and grassroots activism to ask what they would include if they were at the table with members of Congress, negotiating a stimulus package. Among their demands: renewable energy tax credits, community cleanups, and an end to bailouts for oil and gas companies. Their answers have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Forget about fossil fuels

Grist / Courtesy Clark Williams-Derry

Clark Williams-Derry, energy finance analyst, The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis

In my mind, the top climate priority in any stimulus package is like the Hippocratic Oath: Do no harm! Bailouts to the shale industry in particular are like throwing good money after bad. Our research has shown that U.S. fracking-focused oil companies have been money-losers for at least a decade. The underlying financial reality — even before COVID-19, even before the Saudi-Russia price war — is that fracking has been an unrelenting financial failure.

The job of any short-term stimulus must be to help real people with real problems: safeguarding health and surviving the economic crunch. Bailouts to favored industries are a feeble and ineffective way to achieve these goals.

The biggest question we’ll be facing after the short-term crisis passes will be: How do we rebuild? One way of rebuilding the economy is to prioritize investments that put people to work, stabilize the economy, and keep consumer costs low and stable over the long-term. A massive build-out of renewables and storage, focused on distributed generation, looks like both a winner for the climate and for real people.

[Editor’s note: Williams-Derry worked for Grist in its early years, back at the turn of the century.]

Green infrastructure and neighborhoods

Grist / Courtesy Lynn Richards

Lynn Richards, president and CEO, Congress for the New Urbanism

We have historically spent lots and lots of money, trillions of dollars, on these big infrastructure projects. Think the Hoover Dam and the Tennessee Valley Authority. What happens if we begin to turn our attention to the neighborhood, to millions of small-scale projects?

What about creating a program for green infrastructure around schools? Stormwater management — which is actually very labor-intensive to build — has so many auxiliary benefits, such as increasing the walkability of a particular street, creating a more distinctive community, slowing down traffic, creating more green space, and oh, by the way, managing your stormwater.

Spend some of that money to have parents who got laid off build rain gardens around the schools. Every single school in America could have a rain garden. It would put people back to work, and it would help create a greater sense of community. To buy materials, you’d have to support local landscaping businesses. It’s all very much local and small-scale. That’s something that could easily be done by this summer. We’re not talking about building a 12-mile highway. We need to immediately jumpstart the economy in a way that will provide multiple community benefits.

Back in the Great Depression, we had the Civilian Conservation Corps. What happens if we were to create a similar program that built affordable housing or Missing Middle housing in cities across America? If each city were only able to build 100 or 200 units, that would be enormous. If we start building more complete neighborhoods that are more compact, so we’re not required to drive everywhere, we’re going to start chipping away at the 30 percent of emissions that come from transportation.

When you’re talking about transportation, the ramp-up to do that is much harder. I can think of a trillion dollars of expenditures on transportation from investing in bus rapid transit, in streetcars, fixed rail, bike lanes, more walkable streets, fixed sidewalks, pedestrian dignity. That’s something I would want to see in the longer term.

Make sustainable investments

Grist / Courtesy Bracken Hendricks

Bracken Hendricks, president & CEO, Urban Ingenuity

Stimulus and recovery funding is exactly what needs to be done. It’s exceedingly timely, and it’s actually where the movement for climate solutions needs to go anyway. I think it’s sort of a silver lining of a terrible situation.

In the short-term, I think the first thing we want to do is actually tie standards to the money we’re giving away. If you’re subsidizing energy-intensive and highly polluting industries, you really should stipulate that they create more public value in return for a bailout. Whether it’s cruise ships or casinos or the hospitality industry, there’s a ton that they can do to clean up their environmental performance, use more renewable energy, and use more energy efficiency.

Clearly, you want to think twice about bailing out the oil and gas industry, but if you’re going to do that, you want to really think about what you’re asking for in return. When the government bailed out the auto industry [in 2008], they stepped up and made commitments to improve fuel economy. It’s a very good precedent. And we should be doing that throughout any business-focused bailout dealing with emergency situations. It’s not unreasonable. These are core pieces of the public value.

I worked very deeply on the Recovery Act, which included billions for clean energy investments. You had advanced manufacturing of vehicles and building plants for the electrification of vehicles. There were things like the Energy Efficiency and Conservation BLOCK Grant program that pushed money through HUD to towns and cities to do energy efficiency, renewable energy, bike lanes, and a whole range of things that decarbonized at the community level.

I really do think this is a leadership opportunity, assuming that former Vice President Biden is very close to sowing up the nomination mathematically. The Vice President’s office in the Obama administration oversaw huge portions of the Recovery Act. And Joe Biden actually has a really, really strong record of leadership. The $90 billion in the Recovery Act, a lot of it was under his guidance. So I think leaning into having him expand his climate ambition through the vehicle of a green recovery program is not at all far fetched.

A large stimulus package could be moving at the trillion-dollar scale. No. 1, we better make sure that those investments are flowing to things that are actually sustainable.

Avoid austerity

Grist / Justin Sullivan / Getty Images

May Boeve, executive director, 350.org

The Sierra Club put together a package that they sent to the Hill that we think is really, really good. The key bullet points that they included in their note were: invest in workers, protect clean energy, clean transportation, and clean economy jobs, no fossil fuel bailouts, make a down payment on a regenerative economy, and protect democracy.

[The novel coronavirus] is revealing just how interconnected everyone is — the terrifying part is not the interconnectedness, obviously — but it’s the spread of this, and how it had a global reach so quickly, that reminds everyone that one country’s response is insufficient. We have to be thinking globally.

We need increased public spending and an end to austerity on a global level. This pandemic has demonstrated that a huge and growing portion of the planet’s labor force is working under increasingly precarious conditions. In many places and not only in poorer countries, people are forced to choose between feeding their families and social distancing, and this crisis has revealed so many systemic problems in the way the economy is set up and how that affects the most vulnerable.

Some of the things connected to that that we’re calling for are increased public health budgets, livable minimum wages, income security, massive retraining programs to make sure those left unemployed and those in unsustainable industries can find jobs. As we know, massive government investment in public infrastructure is also what’s going to help us combat future shocks caused by climate change, and it’s also going to be what helps us build the low-carbon infrastructure we need. That takes us further away from catastrophic climate impacts, and builds the green economy that we need for the future.

Leave no community behind

Grist / Courtesy Michele Roberts

Michele Roberts, national co-coordinator of the Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform

We need to see how it is that the vulnerabilities that were permitted through things such as racial segregation, forced migration, all of these things that stem back to racial and ethnic discrimination — how are we addressing remedies to make people whole in these stimulus packages as we look at climate change and the climate crisis and now this pandemic coronavirus crisis?

Because of our unified and combined work together on the Equitable and Just Climate Platform, and the newly introduced Environmental Justice For All bill, fortunately, our communities have been reached out to by policymakers. And so we have been able to share the things that we need. Short-term fixes, such as making sure, No. 1, that these funds that are coming into states literally drop down on the ground to the most impacted, not just go back into the state budget. But making sure that it helps families with folks who are incarcerated. We’re talking about children being at home and learning now through the internet — we still have a digital divide when we think about our brothers and sisters in Appalachia and in northern New Mexico and Colorado and other spaces. So making sure digital infrastructures are reinforced, and that we prioritize those who still have yet to gain necessary digital infrastructure. Making sure that our community roads and systems — sewer lines and the like — are addressed. That there is access for our senior population and our children to healthy nutritional, affordable foods, not these foods laden with high sodium and artificial ingredients. Our folks need access to healthy, nutritional, affordable food and affordable medication. All of these things are necessary.

For our long-term stimulus package, that’s when we really get down into the nitty-gritty of making sure that there is a comprehensive cleanup for our communities. That cleanup does not mean that our community members are thrown out — they are able to live in the communities that have been brought up to the standards that other communities have.

Clean energy tax credits

Grist / Courtesy Niskanen Center

Joseph Majkut, director of climate policy, Niskanen Center

There’s a bunch of clean energy tax credits that could plausibly be included in this stimulus. Examples might include reform or expansion of the electric vehicle tax credit, tax credits for energy storage, or for various kinds of new low-carbon technology.

Industry is asking for those tax credits. It’s not clear to me how much those measures will stimulate the economy — given that the economy is entering a very ambiguous period, there’s going to be a lot of demand for money. I don’t know how I would handicap clean energy credits’ chances versus other demands for funding. Still, when the government is handing out money, there’s no sense in not raising your hand.

I think a lot of the things that we need for the long term have a longer timescale than I think they’re contemplating right now, like deploying new technology — high voltage power lines crossing the country, green infrastructure, public transport. That’s not the stuff that can get slotted into fast-moving legislation. But it might be reasonable to look at later in the year, depending on how long this recovery takes.

If we are talking about looking all the way forward to rebuilding under a new president, I think we need to wait and see what the effect of this recession is regionally. We’ve got to know more to understand how we’re going to stimulate the economy before we can really simulate what we’re going to plan for climate efforts.

Advanced manufacturing in underserved communities

Grist / Rowan Daly

Mustafa Santiago Ali, vice president of environmental justice, climate, and community revitalization, The National Wildlife Federation

I’ve been pushing folks to actually have an environmental justice aspect put into it to make sure that any reactions that happen are not going to have disproportionate impacts on communities of color and indigenous populations. So [my plan would] be focused on the opportunities that exist around renewable energy in a couple of different ways: one, making sure that any movements that we go forward on are lowering emissions and public health impacts. It would be focusing on wind, solar thermal, tidal, and making sure that we are creating advanced manufacturing opportunities — and those advanced manufacturing opportunities are in the communities that have often been under-resourced and underserved. [Editor’s note: “Advanced manufacturing” refers to industrial processes that are optimized for efficiency using scientific and technological innovation.] For me, that’s hugely important as somewhere between a trillion and maybe possibly up to $3.5 trillion begins to move back to our economy.

Contributors: Yvette Cabrera, Nathanael Johnson, Shannon Osaka, Emily Pontecorvo, Rachel Ramirez, Naveena Sadasivam, Nikhil Swaminathan, Zoya Teirstein