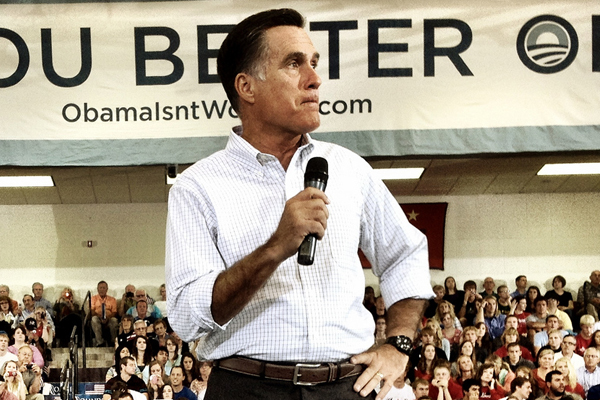

This Sunday’s New York Times Magazine features a long retrospective on the tenure of a particular Massachusetts governor. You know the guy: salt-and-pepper hair, winning smile, 45 kids. Name escapes me.

It’s the sort of article that responsible citizens should carve out 30 minutes to read. For the first time that I’ve seen, it walks through how Romney governed — and how, halfway through his first and only term in office, he began to rejigger his positions with an eye toward the presidency.

What’s most notable, and most of interest for the average Grist reader (if I may be so bold), is how Romney reversed (or, if you will, substantially amended) his position on the environment. His 2003 declaration that coal plants kill people gets the press during this election, but his 2004 outline of a comprehensive plan for combatting climate change was probably a high-water mark.

According to one of a half-dozen environmental officials with whom I spoke (and all of whom insisted on anonymity so they could speak candidly about their experiences), the governor sat through more than 20 hours of briefings on the climate-change plan: “We went through about 80 measures. He left almost everything in, and the things he took out weren’t because they were ideologically off-base but because they weren’t well thought out.”

A sentimental subtext underlay his conservationist outlook: his father’s company had produced one of the world’s first fuel-efficient cars. And when discussing the global dimensions of climate change, the governor displayed a level of humaneness that fellow congregants in his Mormon church often saw but that his current presidential campaign has been at pains to highlight. Two environmental officials recall him saying: “I think the impacts of this are going to be large. We in the Western world may have the money to work our way out of the problem. But what are poor people in Bangladesh going to do?”

And then the tide receded.

Fully a year before unveiling his climate-change plan, Romney agreed to participate in the creation of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI (pronounced “reggie”), a consortium of nine Northeastern states invited by Gov. George E. Pataki of New York to formulate the nation’s first comprehensive cap-and-trade, greenhouse-gas-reduction policy. In a July 21, 2003, letter to Pataki, Romney wrote that “now is the time to take action toward climate protection.” He noted that his administration “has a target of reducing greenhouse gases” and added that “I believe that our joint work to create a flexible market-based regional cap-and-trade system could serve as an effective approach to meeting those goals.” The concept appealed to Romney’s penchant for cutting-edge solutions. One of Romney’s top officials told me that if the states had been able to finalize an agreement during the first year and a half of Romney’s term, “there’s no question he would have signed. No doubt about it.”

But Romney’s desire to be bold on climate change wasn’t shared by fellow Republicans. …

Both sides met in Romney’s office in December 2005. Though the setting was a Bain-like unemotional inquisition, the ex-C.E.O. seemed only selectively interested in the data. “He kept saying, in effect, ‘Yeah, but you can’t guarantee the prices won’t go higher,’ ” recalls one of the people with knowledge of the meeting. And Renee Fry, who represented the businesses seeking to jettison RGGI, says, “As we were leaving, he said, ‘I’ve got to think about how this is going to affect jobs.’ ” Romney’s desire to lead the nation on climate change had vanished from the discussion.

On Dec. 14, 2005, Romney publicly announced two things: that Massachusetts was withdrawing from RGGI and that he would not be seeking a second term as governor.

Now, of course, Romney considers climate change a punchline.

The most telling excerpt on Romney’s climate change evolution is this one.

“Have you seen the movie ‘Animal House’?” one of Governor Romney’s environmental officials asked me. “You remember that character who has the angel on one shoulder and the devil on the other, both telling him what to do? Watching Romney, my sense was that he was always inclined to do the right thing on environmental issues. But then there was the devil on the other side. You could almost see it. It was palpable. Clearly, in retrospect, he was weighing what was right for Massachusetts with how it would play nationally.”

One question for environmentally conscious voters, then, is this: How might a President Romney weigh what is right for the country on environmental issues? It’s unlikely he’ll answer that directly at the debate — and if he does, we’ll have no way of knowing if that’s what will actually happen.

Our best guide is his record. So the real question is: Which vintage Romney would we get, 2003 or 2005? And, equally important, which Romney would appear shortly before his reelection campaign?