Those parents who choose not to vaccinate their kids? If we just batter them with enough graphs and quips and indignation, eventually, they’ll change their minds.

That, at least, seems to be the operating assumption of my Twitter and Facebook feeds right now. The torrent began with the news of the measles outbreak at Disneyland, and increased when Rand Paul and Chris Christie made some ill-advised remarks about vaccination.

Vaccination snark bothers me because I remember what it felt like when I was suspicious of vaccination myself, in the back-to-the-garden town where I grew up. At the time, sniping didn’t make me feel dumb or alone. It made me feel superior and smart. I felt like I was one of a small group of people who actually understood the nature of scientific doubt; everyone else was parroting memes and repeating superficial points without any deep comprehension of the issue. Yes, I could see that many people who feared vaccines were blindly fearful — but also that many of the people campaigning for inoculation were blindly compliant.

There’s a powerful instinct, when something like this measles outbreak occurs, to huddle into a tribal unit by repeating the shibboleths that prove we are all on the same side. At the tribal level, cohesion and shaming works: It makes the odd-ones-out extremely uncomfortable. Eventually, they’ll abandon their beliefs, exile themselves, or hide their differences.

But in our modern world, as Brendan Nyhan and David Ropeik recently pointed out, shaming will only make the problem worse. It drives people into exile, yes; but in a populous, diverse, and technologically interconnected society, exile simply means huddling into another, more like-minded tribe, just a click away.

One of Nyhan’s studies in particular seems to drive my most vocal pro-vaccine friends crazy. Nyhan and his collaborators tried to see if they could change people’s minds about vaccination by giving them information. They found that, when you tried to use evidence to make a case, it backfired: Anti-vaccination convictions deepened.

I’m not sure why anyone is surprised or infuriated by this. We’ve known for years that the information deficit model fails: You can pile all the facts you want on someone, but it’s just going to make them angry if they assume it’s BS. And if they don’t trust you, they’re going to assume it’s BS. (David Roberts has written a lot about this as it relates to climate skepticism.)

Suppose someone shows up at your door and says, “I have some good news I’d like to share with you about our lord and savior!” How likely do you think it is that information is going to change the way you think about anything? If that’s the way the world worked, we would all be Jehovah’s Witnesses by now.

Clearly, there’s better evidence to support the efficacy of vaccination than there is to support the efficacy of any particular religion, but that doesn’t matter. To evaluate evidence, you need to be willing to dedicate a lot of time to it, and more importantly, you have to trust and understand the systems that produced the evidence.

This also applies to debates about climate and about genetically engineered foods. Climate change deniers, and people who say vaccines and GMOs are too risky, all take positions contrary to the positions of the majority of scientists. It’s often suggested we should cut off debate and simply defer to Science on these issues. But nobody outsources decision making to the scientific majority. You are welcome to yearn for a culture that unquestioningly trusts an elite echelon of scientists, but it’s not how society works. That’s also not how science works; everything is always up for debate.

So how do you persuade someone, if not through education or gesturing at scientific authority? Well, you start by abandoning the goal of persuasion. Instead, set out to truly care for that person who you disagree with. Minds close under adversarial barrages of information. Minds open when engaged in collaboration with trusted partners. We don’t suffer from lack of education — we suffer from a lack of kindness.

Consider the interaction between a pediatrician and a parent with vague doubts about vaccines. All too often it goes something like this:

Parent: I’m a little embarrassed to bring this up, doc, but I have to tell you, I’m worried about vaccination. I promise I’m not one of those people. I just really don’t trust the Pharma-Industrial Complex, and I don’t like the idea of giant corporations profiting off technologies that go into our bodies.

Doctor: Well, here’s a printout of our policy on vaccinations, and let me also give you this information sheet. That should answer all your questions.

No. No, it won’t. You might as well be handing out copies of the Watchtower.

Many doctors communicate much more than this, but I’ve also heard plenty of stories of doctors who cringe away from the discussion. Even the best doctors don’t have time for the conversation that’s required. Katya Gerwein, a wonderfully kind pediatrician in Berkeley, tells me she does her best — she’ll book special appointments to help vaccine-hesitant parents navigate the evidence. She believes wholeheartedly in this process, but it’s also difficult for her, because it has to be pro-bono: she isn’t reimbursed for heart-to-heart discussions or for building relationships.

And, this, I think, is the central problem. Vaccine hesitancy is a natural symptom of a medical system that values technical fixes but not relationships. Imagine if patients knew their doctors well enough to trust that their recommendations were not some one-size-fits-all guideline, but what was really best for their family. Imagine if doctors and patients truly felt that they had considered the risks and benefits of each treatment collaboratively, until they confidently reached a mutual decision. If doctors could truly know each patient as an individual, and patients truly trusted their doctors, this whole vaccine-refusal issue would vanish like a puff of smoke.

This sounds expensive. But the most expensive parts of our healthcare system — treating patients at the end of life, and treating diet-related diseases — are expensive precisely because we default to technical fixes rather than investing in relationships, culture, and coaching.

Not every solution has to be so warm and fuzzy. Shaming people doesn’t help, but it does work to pass sensible laws that nudge people toward becoming a responsible member of the common-health. It makes a lot of sense for a society to make rules to protect itself from people who make dangerous choices. For example: I think I should be allowed to decide that vaccination isn’t right for my family, but the public doesn’t need to accept the risk of allowing my family in schools. If I decide that stopping at stoplights isn’t right for my family, society would eventually tell me that I needed to stay off public roads.

As my colleague Ben Adler points out, you don’t need to persuade people to get results: The state with the highest vaccination rate, Mississippi, permits no non-medical exemptions from school vaccination requirements. One poll shows that over 65 percent of both Republicans and Democrats think that all children should be required by law to get vaccinations. Surely, the overwhelming majority of voters would favor much less coercive measures, like ending personal belief exemptions at schools.

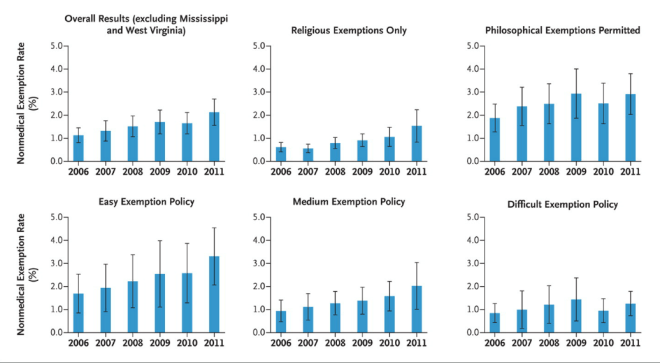

Rates of Nonmedical Exemptions from School Immunization Omer et. al

I would vote for that. I’d also like to have the chance to vote for a health system that valued relationships and culture. Let’s not lose sight of the fact that people choosing not to vaccinate is a relatively small problem, at this point. There are many bigger problems we could take on. The No. 1 cause of death among children in America is injuries: cars, drowning, guns.

If the current trend continues, however, vaccine refusal will become a big problem. In states with more permissive rules for school vaccination, the number of exemptions is increasing at an average of 13 percent a year. And there’s a couple of key differences between this issue and our arguments over climate change or GMOs: When it comes to vaccination, the overwhelming majority of Americans are on the same side. Also, the fix is simple.

I see vaccine refusal as a symptom of a larger problem with our medical system, but that doesn’t mean it’s insignificant. Symptoms can kill. Let’s treat the symptoms, and redouble our efforts to address the underlying disease.