Cars, trucks, and other motor vehicles are the source of 11 percent of fine particulate air pollution and 28 percent of nitrogen oxide pollution in New York City. On Thursday, Mayor Bill de Blasio introduced a new initiative to try to make a dent in that pollution by harnessing the star power of, uh, Billy Idol to try to get New York drivers to stop idling. (Because “idle” sounds like “Idol” — get it?)

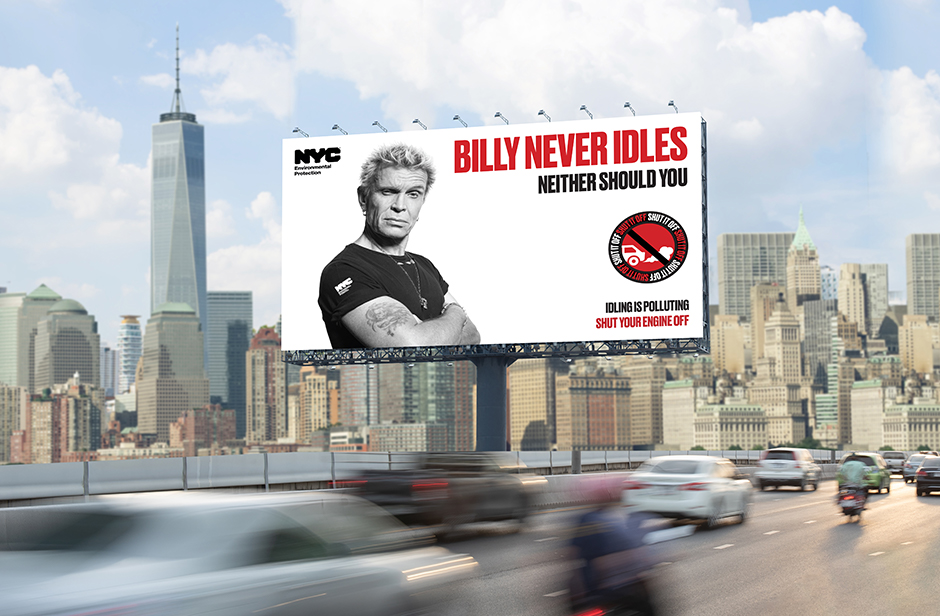

At a press conference in front of City Hall, de Blasio and Idol announced a $1 million publicity campaign to encourage drivers to turn off their engines when their cars are stopped. During the month of March, billboards, gas stations, radio stations, kiosks, and the little TV screens inside yellow taxis will bear ads telling drivers, “Idling is polluting. Shut your engine off.” The billboards feature a picture of the British rock star glowering at the camera next to the words, “Billy never idles. Neither should you.”

Alongside the new campaign, the city’s Department of Environmental Protection is also expanding a program that allows citizens to report idling freight trucks and buses to the city in exchange for an $87.50 reward once the complaint is verified. The citizen complaint program doesn’t apply to idling passenger vehicles, although it’s technically illegal for anyone in the city to idle for more than 3 minutes or more than 1 minute near a school.

As the new campaign acknowledges, idling is a major problem for human health and the climate. A 2009 study estimated that idling vehicles in New York City produce thousands of tons of pollutants associated with respiratory disease, cancer, asthma, heart disease, and other health effects, along with 130,000 tons of CO2. (The city’s traffic has gotten even worse in the decade since that study took place, thanks in part to the explosion of ride-hail apps and a rise in home deliveries, though the city’s overall air quality has improved due to reductions in the use of heating oil.) Idling trucks are especially bad offenders due to their size and diesel engines: The EPA estimates that idling trucks emit 11 million tons of carbon dioxide, 180,000 tons of nitrogen oxides, and 5,000 tons of particulate matter annually nationwide.

But is telling drivers that a scowling glam-rocker disapproves of their idlingreally the best way to make a dent in pollution from freight trucks? A 2014 study commissioned by New York state linked delivery truck idling — along with related behaviors like circling and double-parking —to “congestion, traffic gridlock, inadequate off-loading facilities and tough parking challenges.” Indeed, delivery trucks idling in bike lanes or traffic lanes while their drivers make deliveries are a very common sight in the Big Apple. More loading zones for freight trucks could ease this problem by giving truck drivers a legal place to park — with their engines off —while making deliveries.

But loading zones require transportation planners to take away street parking — a politically risky proposition in any city, but especially in New York, where free street parking is seen as a birthright by many car owners. After complaints from local residents who were used to parking on the street, de Blasio’s Department of Transportation walked back a loading zone pilot program in one Brooklyn neighborhood last summer. (The pilot program has continued in 10 other neighborhoods and will be evaluated after a year.) Though de Blasio has made some big promises to expand the city’s networks of bike and bus lanes, he generally governs with a windshield perspective: He’s expanded the city’s parking placard program, giving 50,000 more city workers the right to park effectively anywhere without consequence, and he’s famous locally for insisting on being driven 11 miles from the mayor’s residence to his favorite gym in Brooklyn every day. He also repeatedly opposed a congestion pricing plan that would reduce traffic and raise funds for subway improvements and conditioned his ultimate support for the plan on the promise that some drivers would be exempt from the toll. (The congestion pricing plan passed in the state legislature last spring and is now awaiting federal approval.)

At the press conference announcing the “Billy never idles” campaign last week, de Blasio said, “If we stopped unnecessary idling in New York City, it would mean the equivalent of taking 18,000 cars off the road every single day.” It’s emblematic of de Blasio’s overall approach to transportation planning that he’s aiming for the former rather than the latter.