This story is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

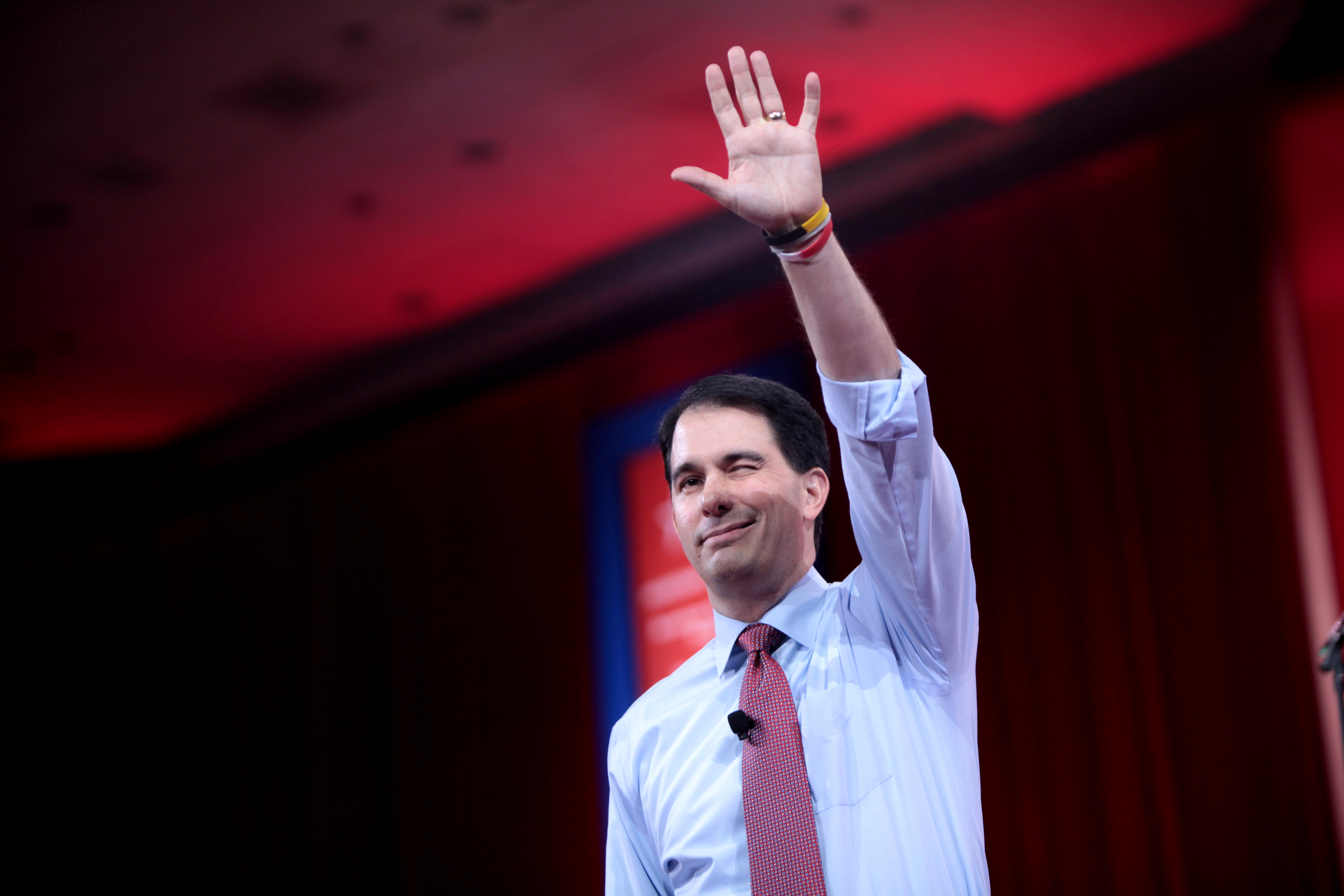

Scott Walker is killing it with Republicans. The Wisconsin governor is one of his party’s rising stars — thanks to his ongoing and largely successful war against his state’s labor unions, a fight that culminated Monday with the signing of a controversial “right-to-work” bill.

Now (for the moment, anyway), he’s a leading contender for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination. At the Conservative Political Action Conference a couple weeks ago, he polled a close second to three-time winner Sen. Rand Paul (Ky.), beating the likes of Sen. Ted Cruz (Texas) and former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush by a significant margin.

It probably won’t surprise you to learn that none of the prospective GOP presidential candidates are exactly champions of the environment. Probably the least bad is New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who at least acknowledges that climate change is real and caused by human activity. Walker just might be the worst. He hasn’t said much about the science of global warming. (In the video above, you can watch him tell a little kid that his solution to the problem will center on keeping campsites clean, or something.) But his track record of actively undermining pro-environment programs and policies while supporting the fossil fuel industry is arguably lengthier and more substantive than that of his likely rivals.

“He really has gone after every single piece of environmental protection: Land, air, water — he’s left no stone unturned,” said Kerry Schumann, executive director of the Wisconsin League of Conservation Voters. “It’s hard to imagine anyone has done worse.”

Here’s a rundown of Walker’s inglorious history of anti-environmentalism.

Attacking Obama’s climate agenda

Walker is a key figure in the GOP’s battle against President Barack Obama’s flagship climate policy — the proposed Environmental Protection Agency rules that are designed to reduce the carbon footprint of the nation’s electricity sector 30 percent by 2030. The rules will likely require states to retrofit or shutter some of their coal-fired power plants. That could be a big deal in Wisconsin, which gets 62 percent of its power from coal.

In a letter to the EPA in December, Walker said the plan would be “a blow to Wisconsin residents and business owners.” He cited an analysis from his state’s Public Service Commission that predicted household electric bills would skyrocket. They won’t, necessarily, since the state has a lot of options — including boosting renewables and energy efficiency — that it could use to meet its EPA carbon target without jeopardizing the power grid. But rather than preparing for the new rules, Walker seems bent on stonewalling them. In January, he announced that his new attorney general was already preparing a lawsuit against the EPA, a move that was lauded by the Wisconsin director of the Koch brothers-backed group Americans for Prosperity. Walker has also signed a pledge, devised by Americans for Prosperity, that he will oppose any legislation relating to climate change — presumably a cap-and-trade plan or a carbon tax — that would result in a “net increase in government revenue.”

Indeed, Walker has close ties to Charles and David Koch, the billionaire brothers who made a fortune in fossil fuels and who for years poured money into groups that cast doubt on the science of climate change. They own paper factories and a network of gasoline supply terminals in Wisconsin, and they have an interest in the state’s trove of “frac sand” (more on that below). Koch Industries gave $43,000 to Walker’s 2010 election campaign, and just after he took office, the Kochs doubled their lobbying force in Madison. In 2011 and 2012, David Koch and Americans for Prosperity spent $11 million backing Walker’s agenda and his successful effort to avoid being recalled.

Turning off clean energy

As much as he apparently supports fossil fuel development, Walker has taken steps to put the brakes on clean energy. Last month, he released a budget proposal that would drain $8.1 million from a leading renewable energy research center in the state. That same budget, however, would pump $250,000 into a study on the potential health impacts of wind turbines. (Wind energy opponents have long suggested that inaudible sound waves from turbines can cause insomnia, anxiety, and other disorders, although independent research has repeatedly found these claims are more connected to NIMBYism than legitimate medical concerns.) Walker’s budget would also cut $4 million in state subsidies for municipal recycling programs. That, at least, is an improvement over his first budget as governor, which proposed to eliminate recycling subsidies altogether.

Budgets aren’t the only avenue for these attacks: In 2011, Walker introduced legislation backed by the Wisconsin Realtors Association to restrict where wind turbines could be built. (That bill was ultimately killed by the legislature.) And the state’s Public Service Commission — which oversees the electric grid and is comprised mainly of Walker appointees — recently launched a campaign to redesign power companies’ rates in a way that solar companies say is meant to kneecap their competitive edge. The commission wants to impose a high fixed charge on monthly bills that homeowners would have to pay even if they purchase their own solar panels.

There is, however, one alternative energy source that Walker suddenly seems willing to support. Pandering to corn farmers in Iowa over the weekend, he flip-flopped his stance on biofuels — as governor, he was opposed to a federal ethanol mandate, but now, as a likely candidate, he’s in favor of it. Backing ethanol may help Walker win support from Iowa caucus-goers, but the climate benefits of biofuels are very much in doubt.

Open to open-pit mining

In 2010, a mining company called Gogebic Taconite LLC began to push hard to establish a large open-pit iron ore mine in the state. Environmentalists vehemently opposed the project, warning that it could damage fragile wetlands and contaminate local air and water with toxic chemicals. But Walker supported it. (In 2012, the company gave $700,000 to the pro-Walker Wisconsin Club for Growth.) In 2013, Walker succeeded in pushing through a bill to relax environmental standards for iron mines that paved the way for the project to be approved once it was reviewed by federal regulators.

Walker also reportedly cultivated an industry-friendly atmosphere at the state’s Department of Natural Resources, the agency charged with enforcing environmental standards. One Democratic state representative said Walker’s pick to head the DNR, a former Republican state senator who was a vocal critic of environmental regulations, was “like putting Lindsay Lohan in charge of a rehab center.” One of the Walker DNR’s first moves was to delay phosphorus pollution standards that were opposed by a Koch-owned paper factory.

In the case of the iron mine, it was all for naught: Last month, the mining company announced it was putting the project on indefinite hold, blaming “cost-prohibitive” federal regulations.

A blind eye to fracking sand

Wisconsin doesn’t have much in the way of shale gas, but it still plays a vital role in the fracking boom. The state is home to a major supply of “frac sand,” a superhard, chemically inert type of silica that props open cracks in underground rock formations during the fracking process. Since 2010, the number of sand mines in Wisconsin has grown more than tenfold, despite widespread complaints that the operations are turning idyllic rural communities into industrial wastelands and that the type of dust produced by the mines is linked to a wide range of serious respiratory health hazards. Walker has been a vocal proponent of the industry, touting it as a source of jobs and investment in an otherwise lackluster economy.

Here again, Walker’s weakened DNR is an issue. In 2013, the state’s independent, nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau estimated that at least 10 full-time DNR employees would be necessary to ensure proper oversight of the frac sand industry. But the report noted that the agency had chosen to hire just two.

“It’s really going, to a large extent, unregulated,” said Tom Thoresen, a veteran DNR conservation officer who retired before Walker became governor but still has friends in the agency. (Thoresen currently sits on the Wisconsin League of Conservation Voters board.)

Indeed, citations for various environmental infractions from the DNR fell 28 percent under Walker compared to the previous administration, according to the Journal-Sentinel.

“The messaging,” added Thoresen, “is to be business-friendly, don’t enforce.”