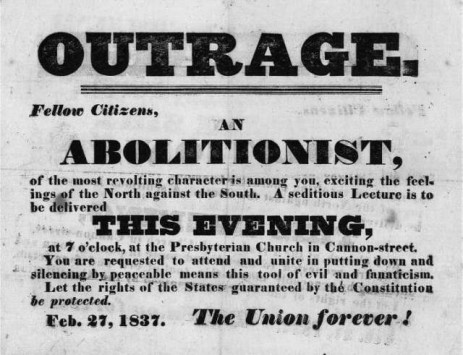

Abolitionists were considered outrageous in their day … and yet.Library of CongressThe problem with relying on World War II as the historical parallel for an energetic, last-minute drive by the U.S. to save the world from climate cataclysm, is that it depends on domestic climate impacts equivalent to Pearl Harbor to kick the whole thing off. I have argued that only such conditions–say, two Category 5 hurricanes passing over Florida in a single season–will be powerful enough to knock business-as-usual-thinking off kilter, and that U.S. environmentalists ought to prepare for rapid, non-linear action within chaotic social circumstances. The problem with that analysis is that it will probably come too late to change the outcome, and it’s too grim to sustain hope.

Abolitionists were considered outrageous in their day … and yet.Library of CongressThe problem with relying on World War II as the historical parallel for an energetic, last-minute drive by the U.S. to save the world from climate cataclysm, is that it depends on domestic climate impacts equivalent to Pearl Harbor to kick the whole thing off. I have argued that only such conditions–say, two Category 5 hurricanes passing over Florida in a single season–will be powerful enough to knock business-as-usual-thinking off kilter, and that U.S. environmentalists ought to prepare for rapid, non-linear action within chaotic social circumstances. The problem with that analysis is that it will probably come too late to change the outcome, and it’s too grim to sustain hope.

Copenhagen has altered the political terrain here in the U.S., providing us an opportunity to aim for rapid political change, more dynamic and more hopeful than waiting for a climate Pearl Harbor. COP15 failed by almost any standard, yet the drive by leaders from island and African nations and 350.org to wrench the world’s understanding of climate from a challenge resolvable by incremental steps within present markets and governmental frameworks to the central moral imperative confronting humanity may well have succeeded.

There are many parallels between our present condition and the decades 1830-50, when the then-moribund drive to end slavery became the dominant question before the nation and flash point for the Civil War. Slavery moved from peripheral concern to central matter of national self-definition through singular actions taken by a handful of remarkable individuals.

Negotiation with slaveholders. The monolithic, inextricable nature of slavery stumped every leader from Thomas Jefferson to Abraham Lincoln, and mainstream anti-slavery advocates, none of whom could envision any exit other than gradual, cooperative measures acceptable to slaveholders, such as voluntary manumission, resettlement of former slaves in Africa or South America, and federal buy-out. Because anti-slavery efforts were deferential to slaveholding states’ interests, they were necessarily long term and in-urgent. Accommodation peaked with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, hailed as the first act by the United States to limit extension of slavery, and embraced by slaveholders because it guaranteed the extension of slavery in new territories below the Mason-Dixon line–a compromise derided by Thomas Jefferson, who observed that “a geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated.”

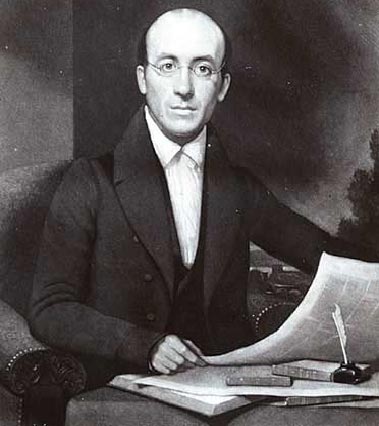

Garrison, the ur-abolitionist.William Lloyd Garrison & abolition. An out of work printer and editor named William Lloyd Garrison stood before an audience of Boston Unitarians and Universalists (the only congregations willing to hear him) on October 15, 1830, and issued the first public call for “immediate, unconditional emancipation, without expatriation,” which, he said, “was the right of every slave and could not be withheld by his master for one hour without sin.” Furthermore, Garrison said, “by holding fellowship with slaveholders,” in their churches, mercantile enterprises, and political parties, New Englanders gave moral sanction to slavery.

Garrison, the ur-abolitionist.William Lloyd Garrison & abolition. An out of work printer and editor named William Lloyd Garrison stood before an audience of Boston Unitarians and Universalists (the only congregations willing to hear him) on October 15, 1830, and issued the first public call for “immediate, unconditional emancipation, without expatriation,” which, he said, “was the right of every slave and could not be withheld by his master for one hour without sin.” Furthermore, Garrison said, “by holding fellowship with slaveholders,” in their churches, mercantile enterprises, and political parties, New Englanders gave moral sanction to slavery.

Garrison’s words divided anti-slavery forces into two camps: those who, through personal prejudice or pragmatic politics, continued to advocate small steps that might past muster in Congress, and those who rallied to his immoderate call for immediate abolition.

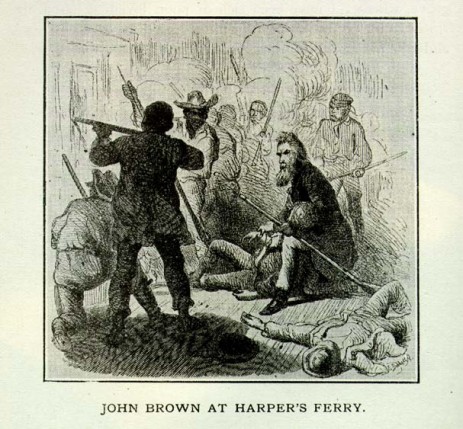

John Brown & Harpers Ferry. Garrison polarized the moral ground, but slavery remained a second-tier concern until John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, in October, 1859, ignited the national furor that led directly to secession, election of Abraham Lincoln, and the Civil War. On May 30, 1880, Frederick Douglass delivered a memorial address, in which he said, “If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery … Until this blow was struck [at Harpers Ferry], the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy, and uncertain. The irrepressible conflict was one of words, votes, and compromises.”

Prolific burning of fossil fuels is no less monolithic, globally, than slavery in the Antebellum South. So too, our organizations and politicians aiming to ameliorate climate change, like anti-slavery advocates, see no alternative but to negotiate with coal and oil interests.

Cap and trade is as disingenuous and fruitless as gradual emancipation, and the Markey/Kerry bill is the moral equivalent of the Missouri Compromise, ostensibly aimed at righting a great wrong, while in substance guaranteeing maintenance of the institution that perpetuates that wrong. The purpose of Markey/Kerry is to ease the minds of those desperate for climate action, even as the extension of coal burning is written into federal law. Its premise is that emancipation from fossil fuels must, perforce, be a gradual undertaking of small steps acceded to by our enemies, with a final accounting made the responsibility of some other generation.

The target of returning below 350 ppm is the critical benchmark defining the problem (with accumulating evidence that “below” is closer to 300 ppm and may require rapid return below pre-industrial 275 ppm), but having already blasted past this mark, 350 ppm alone is ambiguous. How much higher can we safely go? Is 450 ppm an acceptable peak? 550? For how long?

Lacking scientific certainty, we are forced to make judgment calls that amount to playing dice for survival. We stand on no true ground, have no moral compass, and are unable to apply any standard other than ascertaining what we think may be palatable to our enemies.

But Copenhagen clarifies. As environmentalists, we must, and have, acted on behalf of species facing extinction and ecosystems on the road to destruction, but as practical players within a society largely unmoved by such concerns, our central argument must be anthropocentric. We no longer confront speculative injuries remote in time and place; huge populations are on the very brink of catastrophe, with loss of water perhaps the most immediate threat.

Therefore, any act that countenances the extension of fossil fuel burning is wrong. Anything short of immediate and total shutdown of extractions is immoral. That we are all complicit is no justification for acquiescing to evil.

That the violence commences with extractions recognizes the injustice done to local peoples, whether they be in Appalachia or Nigeria; but more profoundly, we must accept that every investment in fossil fuel exploration and each decision to mine or drill is a deliberate, premeditated, and ruthless act.

To say this is to state the obvious. Yet if this is so, and if we continue our rush toward self-induced cataclysm, then why do we continue to treat with the prime authors of our mass suicide?

Look at BP–“Beyond Petroleum”–with its flowery logo and bold vision of transforming energy supplies. BP CEO Tony Hayward caused a stir last year when it was reported that the company planned to sell off its renewable energy division,* but this was a small kerfuffle compared to the overall perspective, in which BP has never deviated from its drive to overtake Exxon-Mobil as the major fossil fuel company in the world.

For two decades now, environmentalists have courted BP (once led by another John Browne). Environmental Defense conducts joint programs, ED and NRDC head up USCAP with BP, and CERES, our environmental voice within the investment world, conferred an award on BP. To what end? In the twelve years since BP first teamed up with ED, BP’s profit has risen from $2.8 billion to $25.5 billion, with the overwhelming bulk of investment going to fossil fuels. Capital expenditures and acquisitions in 2008 alone totaled $30.7 billion, against which BP’s pledge of $1.25 billion annually over 10 years for renewable energy is paltry, even assuming the promise is kept. It may once have been reasonable to try negotiating with BP and others, but no longer.

Time to take a page from John Brown’s book?Something other than dialogue is required. John Brown provided that kick-in-the-pants to complacent anti-slavery efforts by the attempt to capture the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry and ignite a slave rebellion, succeeding in the end in getting two sons and a number of other followers killed, and himself hung. Poorly conceived and without hope of success, the raid and John Brown’s bearing through trial and execution nonetheless galvanized both sides, polarizing and elevating the conflict around slavery.

Time to take a page from John Brown’s book?Something other than dialogue is required. John Brown provided that kick-in-the-pants to complacent anti-slavery efforts by the attempt to capture the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry and ignite a slave rebellion, succeeding in the end in getting two sons and a number of other followers killed, and himself hung. Poorly conceived and without hope of success, the raid and John Brown’s bearing through trial and execution nonetheless galvanized both sides, polarizing and elevating the conflict around slavery.

That Brown’s action was violent and murderous reflected both the author and the times, a thing to be firmly eschewed. Non-violent civil disobedience is the means for direct moral action, as the waves of protest at coal plants, in the mountains of West Virginia, on the Boston Commons and before the offices of organizations that continue to collaborate demonstrates.

Slavery ended in the United States when it did because slaveholders over-reached, but the end of the peculiar institution could not have been avoided. Abolition would have been delayed, however, absent the actions of Garrison and Brown. Time, of course, we do not have, so it is incumbent upon us to take up the same challenge that Garrison made of the citizens of Boston: to examine in what ways our organizations and associations aid and abet the practice of evil; to take direct, non-violent action to halt those practices; and, if we are not so situated, to provide all possible assistance and aid to those in the front lines in West Virginia, Boston, and coal blockades across the nation.

* Hayward quickly retracted the statement, reaffirming BP’s commitment to renewables and carbon emissions reduction, yet the company has taken a number of contrary actions, including recent sale of Indian wind farms, complete withdrawal from the UK renewable sector, and repudiating a pledge to capture and store carbon in natural gas extractions.