This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Last month, in a joint interview with Mother Jones and The Weather Channel, Elizabeth Warren promised that if elected, she’d use the power of the president to address climate change. “I will use all the executive power tools available to me to fight back against the climate crisis,” she said. Listing a few examples, she proposed using executive action to ban drilling and mining offshore and on federal lands and to do away with the practice of fracking.

But would Americans support these dramatic moves?

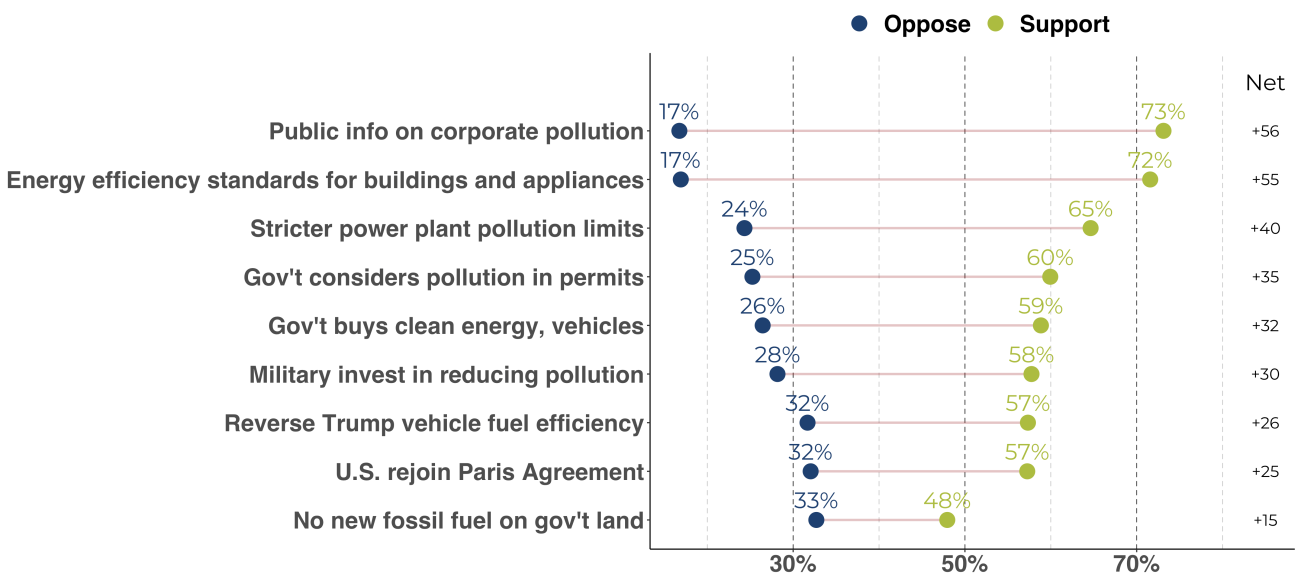

A new national poll provided exclusively to Mother Jones suggests they would. The left-leaning think tank Data for Progress and YouGov asked more than 1,000 voters whether they supported nine ways the next presidential candidate could address climate change. Here are the results:

Data For Progress / Mother Jones

Clearly, the two most popular ideas were “Public info on corporate pollution” and “Energy efficiency standards for buildings and appliances.” If a president wanted to accomplish these goals, says Harvard Law School’s Environmental and Energy Law Program executive director Joe Goffman, he or she wouldn’t necessarily need the approval of Congress — there’s plenty of precedent for executive action. For example: Elizabeth Warren has proposed legislation forcing companies to disclose the environmental harm they cause as well as their risk of being affected by climate change through her Climate Risk Disclosure Act. But Goffman noted that a president could do the same thing through the Securities and Exchange Commission, whose members are appointed by the president, but is otherwise independent.

Those two most popular policies are also the only ideas that attracted support from a majority of respondents who identified as Republican — they were largely against everything else suggested in the survey. I suspect that Republican respondents didn’t come out strongly against those ideas because neither corporate pollution disclosure nor energy efficiency improvement have been high-profile targets of President Donald Trump, who has a polarizing effect on whatever policy he decides to embrace. To wit: Note that some of the biggest partisan splits were on “U.S. rejoin Paris Agreement,” and “reverse Trump vehicle fuel efficiency.”

The upshot of all this: While many Democratic candidates have focused on the bundle of progressive climate legislation known as the Green New Deal, most of the ideas in the poll wouldn’t require Congressional support — and most voters would likely approve if a president used executive power to make these bold changes.

“It’s clear that the public supports greater federal action on climate change,” Leah Stokes, a political scientist at UC Santa Barbara who reviewed the polling.

In May, I surveyed legal experts about what a president could do on climate change if he or she was really going bold, but only using existing law. Under the surprisingly durable elastic statutes of the Clean Air and Water Acts, my experts said, a president could get the United States a lot closer to 100 percent clean electricity, transportation, and efficient, cleaner buildings.

There is one possible exception: banning fracking on public lands. While Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris have all expressed interest in using executive power to accomplish this goal, many experts, including Goffman, just don’t think it can be done without Congress. What a president could potentially do, they note, is review how the Department of Interior leases land for fossil fuel development — for instance, President Obama issued a moratorium on coal from public lands.

“One of the most important things a future president can do is stop all new oil and gas development on public lands,” says Stokes. “Just about 50 percent of American support this, and one in five isn’t yet sure what to think.” Stokes thinks it “bodes well” for a president’s mandate to tackle fossil fuel production on public lands. Overall, Stokes says she believes the level of public support for the ideas in the poll indicates that the American public supports dramatic action to prevent the worst effects of climate change — and she hopes the next president takes notice.

Indeed, Goffman explains, it’s not just the “level of effort or goals or size of emissions reductions that defines ambition,” for presidential candidates, but “how committed the president is to exhausting the tools at his or her disposal.”