This article was produced in partnership with The Intercept.

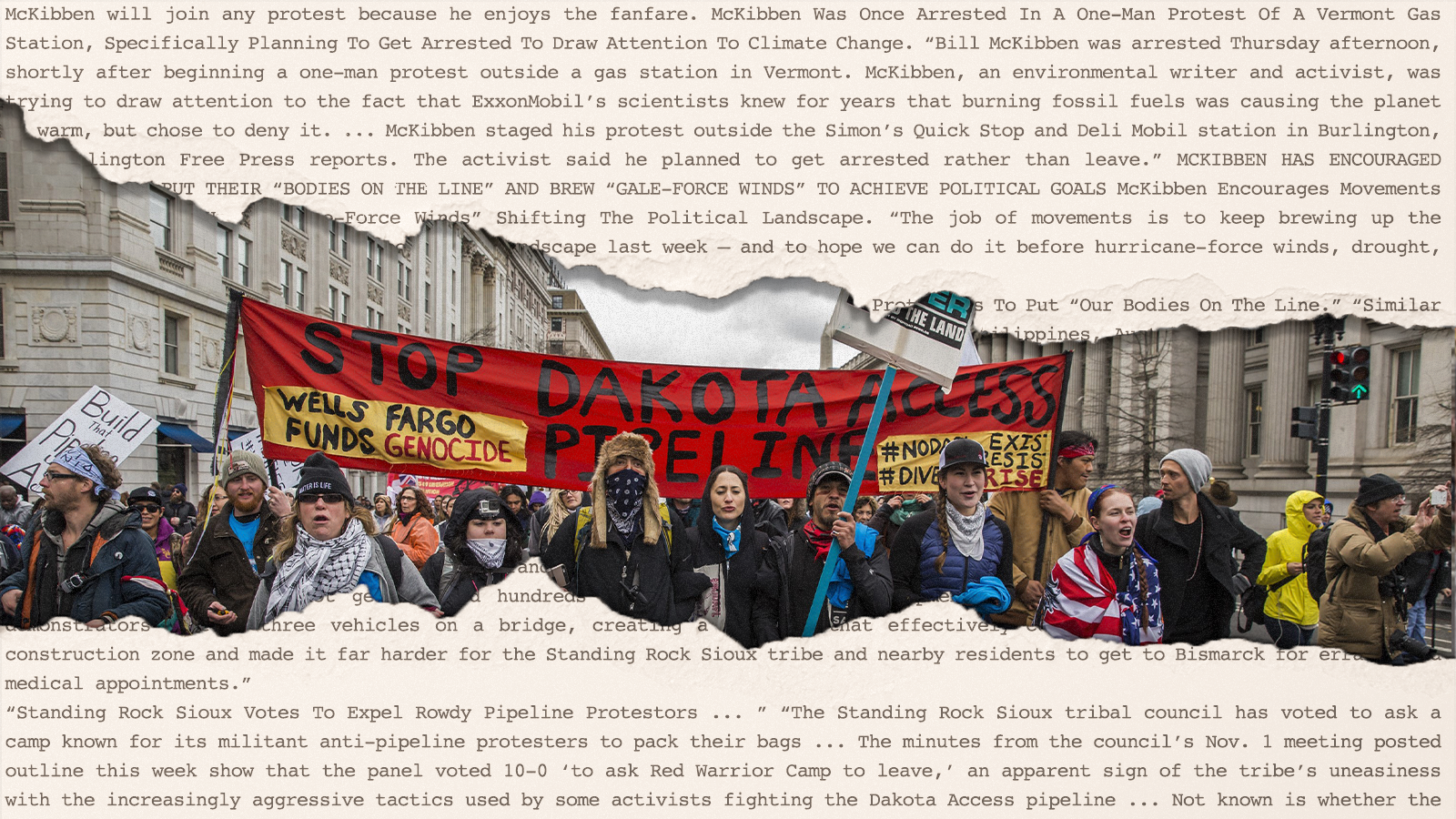

Their protest encampment razed, the Indigenous-led environmental movement at North Dakota’s Standing Rock reservation was searching for a new tactic. By March 2017, the fight over the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline had been underway for months. Leaders of the movement to defend Indigenous rights on the land — and its waterways — had a new aim: to march on Washington.

Native leaders and activists, calling themselves water protectors, wanted to show the newly elected President Donald Trump that they would continue to fight for their treaty rights to lands including the pipeline route. The march would be called “Native Nations Rise.”

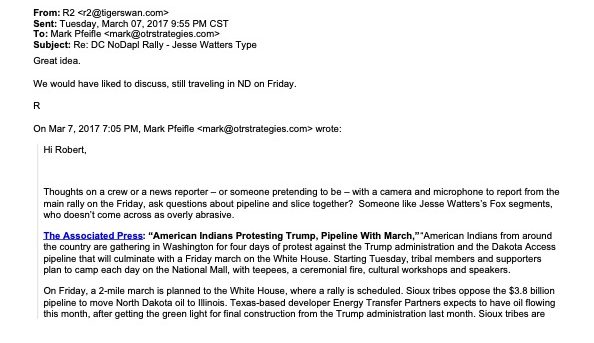

Law enforcement was getting ready, too — and discussing plans with Energy Transfer, the parent company of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Throughout much of the uprising against the pipeline, the National Sheriffs’ Association talked routinely with TigerSwan, Energy Transfer’s lead security firm on the project, working hand-in-hand to craft pro-pipeline messaging. A top official with the sheriffs’ public relations contractor, Off The Record Strategies, floated a plan to TigerSwan’s lead propagandist, a man named Robert Rice.

“Thoughts on a crew or a news reporter — or someone pretending to be — with a camera and microphone to report from the main rally on the Friday, ask questions about pipeline and slice together?” Mark Pfeifle suggested over email.

A security firm led by a former member of the U.S. military’s shadowy special forces, TigerSwan was no stranger to such deception. The company had, in fact, used fake reporters before — including Rice himself — to spread its message and to spy on pipeline opponents. The National Sheriffs’ Association’s involvement in advocating for a similar disinformation campaign against the anti-pipeline movement has not been previously reported.

The email from the National Sheriffs’ Association PR shop was among the more than 55,000 internal TigerSwan documents obtained by The Intercept and Grist through a public records request. The documents, released by the North Dakota Private Investigation and Security Board, reveal how TigerSwan and the sheriffs’ group worked together to twist the story in the media so that it aligned with the oil company’s interests — seeking to pollute the public’s perception of the water protectors.

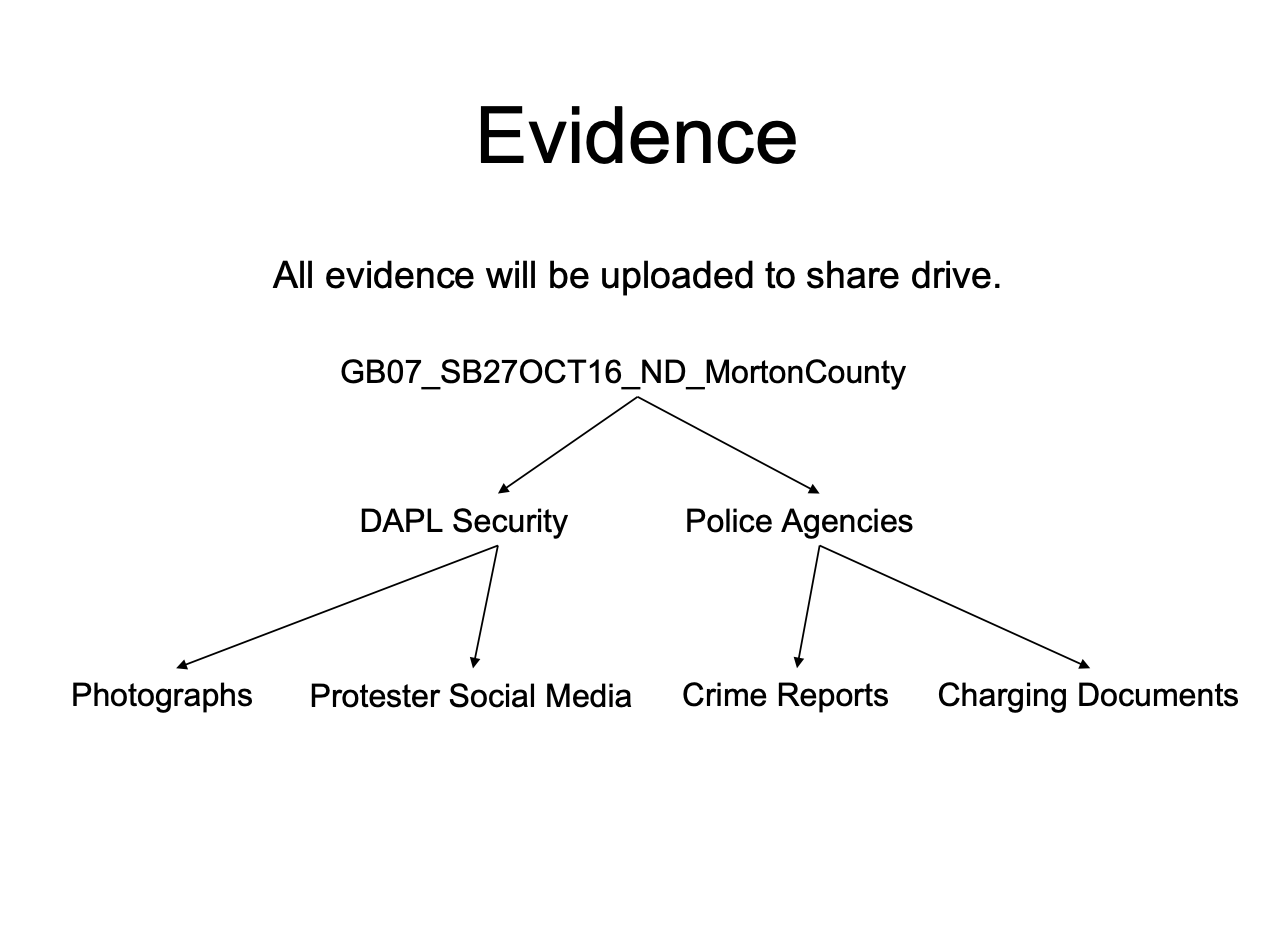

The documents also outline details of previously unreported collaborations on the ground between TigerSwan and police forces. During the uprising at Standing Rock, TigerSwan provided law enforcement support with helicopter flights, medics, and security guards. The private security firm pushed for the purchase by Energy Transfer of hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of radios for the cops. TigerSwan also placed an order for a catalog of so-called less-lethal weapons for police use, including tear gas. The security contractor even planned to facilitate an exchange where Energy Transfer and police could share purported evidence of illegal activity.

Meanwhile, communications firms working for Energy Transfer and the National Sheriffs’ Association worked together to write newsletters, plant pro-pipeline articles in the media, and circulate “wanted”-style posters of particular protesters, the documents show. And the heads of both the National Sheriffs’ Association and TigerSwan engaged in discussions on strategy to counter the anti-pipeline movement, with propaganda becoming a priority for both the police and private security.

“It is extremely dangerous to have private interests dictating and coloring the flow of administrative justice,” said Chase Iron Eyes, director of the media organization Last Real Indians and a member of the Oceti Sakowin people. Iron Eyes was active at Standing Rock and mentioned in TigerSwan’s files. “We learned at Standing Rock, law and order serves capital and property.”

Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier, whose jurisdiction in Morton County, North Dakota, abuts the Standing Rock reservation, said collaboration with pipeline security was limited. “We had a cooperation with them in reference to the pipeline workers’ safety while conducting their business,” he said in an email. “TigerSwan was not to be involved in any law enforcement detail.” (TigerSwan, Energy Transfer, and the National Sheriffs’ Association did not respond to requests for comment.)

Rice, the TigerSwan propagandist, had posed as a news anchor for anti-protester segments posted on a Facebook page he created to sway the local community against the Standing Rock protests. But when Pfeifle, the sheriff group’s PR man, suggested pretending to be a reporter at the Native Nations Rise protest, Rice was unavailable. Pfeifle found another way to tell the pipeline and police’s story: a far-right news website founded by former Fox News host Tucker Carlson. Pfeifle wrote to Rice: “We did get Daily Caller to cover event yesterday.”

The idea of working with police was baked into Energy Transfer’s arrangement with TigerSwan. The firm’s contract for the Dakota Access Pipeline specifically assigned TigerSwan to “take the lead with various law enforcement agencies per state, county, state National Guard and the federal interagency if required.”

Cooperation between Energy Transfer’s security operation and law enforcement, however, began even before TigerSwan arrived on the scene. A PowerPoint presentation from Silverton, another contractor hired by Energy Transfer, described its relationship with law enforcement as a “public private partnership.” The September 2016 presentation said that a private intelligence cell was “coordinating with LE” — law enforcement — “and helping develop Person of Interest packets specifically designed to aid in LE prosecution.”

Multiple documents make clear that part of the purpose of Energy Transfer’s intelligence collection was to support law enforcement prosecutions. A September 2016 document describing TigerSwan’s early priorities said: “Continue to collect information of an evidentiary level in order to further the DAPL Security effort and assist Law Enforcement with information to aid in prosecution.”

The collaboration extended to materiel. TigerSwan operatives realized soon after they arrived that local law enforcement lacked encrypted radios and could not communicate with state or municipal law enforcement — or with Dakota Access Pipeline security, according to emails. Energy Transfer purchased 100 radios, for $391,347, with plans to lease a number of them to law enforcement officers.

”We want them to go to LEO as a gift which represents DAPL’s concern for public safety,” wrote Tom Siguaw, a senior director at Energy Transfer, in an email.

During large protest events, TigerSwan and police worked together to keep water protectors from interfering with construction. On one day in late October 2016, the day of the protests’ largest mass arrest, Energy Transfer’s security personnel “held law enforcement’s east flank” and supported sheriffs’ deputies and national guard members with seven medical personnel and two helicopters, named Valkyrie and Saber.

After the incident, TigerSwan planned to set up a shared drive, where law enforcement could upload crime reports and charging documents and TigerSwan could share photographs and pipeline opponents’ social media. Documents show other instances where TigerSwan set up online exchanges with law enforcement. In a February 2017 PowerPoint presentation, TigerSwan described plans to use another shared drive to post security personnel’s videos and photographs, taken both aerially and on the ground during a different mass arrest.

A Dakota Access Pipeline helicopter also supported law enforcement officials during one of the most notorious nights of the crackdown, when police unleashed water hoses on water protectors in below-freezing temperatures in November 2016. By morning, police were in danger of running out of less-lethal weapons — which can still be deadly, but are designed to incapacitate their targets. TigerSwan and Energy Transfer again stepped in.

TigerSwan founder James Reese, a former commander in the elite Army Special Operations unit Delta Force, reached out to a contact at the North Carolina Highway Patrol. North Carolina had recently used TigerSwan’s GuardianAngel mapping tool to respond to uprisings in Charlotte, in the aftermath of the 2016 police killing of Keith Scott. (A spokesperson from the North Carolina Department of Public Safety said the agency does not currently have a relationship with TigerSwan.)

Reese sent a list of weaponry sought by North Dakota law enforcement to an officer from the Highway Patrol. The list included tear gas, pepper spray, bean bag rounds, and foam rounds. The official referred Reese to a contact at Safariland, which manufactures the gear.

“We will purchase the items, and gift them to LE,” Reese told the Safariland representative. “We need a nation wide push if you can help?”

Meanwhile, another TigerSwan team member sent the Minnesota-based police supply store Streicher’s an even longer list of less-lethal weapons and ammunition. “Please confirm availability of the following price and ship immediately with overnight delivery,” TigerSwan’s Phil Rehak wrote.

Rehak told The Intercept and Grist his job was to procure equipment — including for law enforcement. “I would be given an order by either somebody from TigerSwan or maybe even law enforcement, being like, ‘Hey, can you find these supplies?’” He said he doesn’t know if the less-lethal weaponry was ultimately delivered to the sheriffs.

“I am not aware of any radios for Morton County or any less lethal weapons from Tiger Swan,” Kirchmeier, the Morton County sheriff, told The Intercept and Grist in an email. “I dealt with ND DES for resources.” (Two other sheriffs involved with the multiagency law enforcement response did not answer requests for comment. Eric Jensen, a spokesperson for the North Dakota Department of Emergency Services, said the agency had no arrangement with TigerSwan or Energy Transfer to provide less-lethal weapons, and that they wouldn’t have knowledge of any arrangements between law enforcement and the companies.)

The “partnership” went both ways, with TigerSwan sometimes viewing law enforcement weapons as potential assets. In mid-October 2016, as senior Energy Transfer personnel prepared to join state officials for a government archeological survey to examine the pipeline route, three law enforcement “snipers” agreed to be on standby with an air team, according to a memo by another security company, RGT, that was working under TigerSwan’s management. A Predator drone was listed among “friendly assets” in the memo.

TigerSwan routinely shared what it learned about the protest movement with local police, but most of what the documents describe in the way of reciprocal sharing — from law enforcement to TigerSwan — came from the National Sheriffs’ Association.

In March 2017, the sheriffs’ group helped the South Dakota legislature pass a law to prevent future Standing Rock-style pipeline uprisings, the documents say. To support the effort, the Morton County Sheriff’s Office sent along a “law enforcement sensitive” state operational update from the North Dakota State & Local Intelligence Center. National Sheriffs’ Association head Jonathan Thompson forwarded the document to TigerSwan executive Shawn Sweeney. Thompson recommended Sweeney look at the last page, which included a list of anti-pipeline camps across the U.S.

TigerSwan also recruited at least one law enforcement officer with whom it worked on the ground. In November 2016, Reese requested a phone call with Major Chad McGinty of the Ohio State Patrol, who had acted as commander of a team from Ohio sent to assist police in North Dakota. By February 1, McGinty, who declined to comment for this story, was working for TigerSwan as a law enforcement liaison, earning more than $440 a day.

TigerSwan’s contract also mandated that the firm help Energy Transfer tell its story. The firm was expected “to help turn the page on the story that we are being overwhelmed with over the past few weeks,” according to a document from mid-September 2016.

Energy Transfer’s image was in trouble early on. Critical media coverage of Standing Rock grew dramatically in early September after private security guards hired by the company unleashed guard dogs on protesters. A flood of reporters arrived on the ground to cover the protests. Social media posts routinely went viral. The narrative that took hold portrayed the pipeline company as instigating violence against peaceful protesters.

Energy Transfer recruited third parties to spread its messaging and counter the unfavorable storyline. At least two additional contractors — DCI and MarketLeverage — joined TigerSwan in trying to burnish Energy Transfer’s image. TigerSwan recruited retired Major General James “Spider” Marks, who led intelligence efforts for the Army during the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and served on TigerSwan’s advisory board, to write favorable op-eds and deliver commentary. (Marks did not respond to a request for comment.) With its veneer of law enforcement authority, the National Sheriffs’ Association would become Energy Transfer’s most powerful third-party voice. Representatives for DCI and MarketLeverage and Marks did not respond to a request for comment.

Together, TigerSwan, the National Sheriffs’ Association, and the public relations contractors formed a powerful public relations machine, monitoring social media closely, convincing outside groups to promote pro-pipeline messaging, and planting stories.

Off the Record Strategies, the public relations firm working for the National Sheriffs’ Association, coordinated with the opposition research firm Delve to track activists’ social media pages, arrest records, and funding sources. The companies sought to paint the protesters as violent, professional, billionaire-funded, out-of-state agitators, whose camps represented the true ecological disaster, as well as to identify movement infighting that might be exploited. Both companies were led by Bush Administration alumni. (Delve did not respond to a request for comment.)

Framing water protectors as criminals was a key National Sheriffs’ Association strategy. ”Let’s start drumbeat of the worst of the worst this week?” Pfeifle, Off the Record’s CEO, suggested to the head of the sheriffs’ group in one email. “One or two a day? Move them out through social media…The out of state wife beaters, child abusers and thieves first… Mugshot, ND arrest date, rap sheet and other data wrapped in and easy to share?”

The result was “wanted”-style posters — called “Professional Protestors with Dangerous Criminal Histories” — featuring pipeline opponents’ photos and criminal records, which Pfeifle’s team circulated online and routinely shared with TigerSwan. The National Sheriffs’ Association repeatedly asked TigerSwan to help “move” its criminal record research on social media, and TigerSwan repurposed the sheriffs’ group arrest research for its own propaganda products.

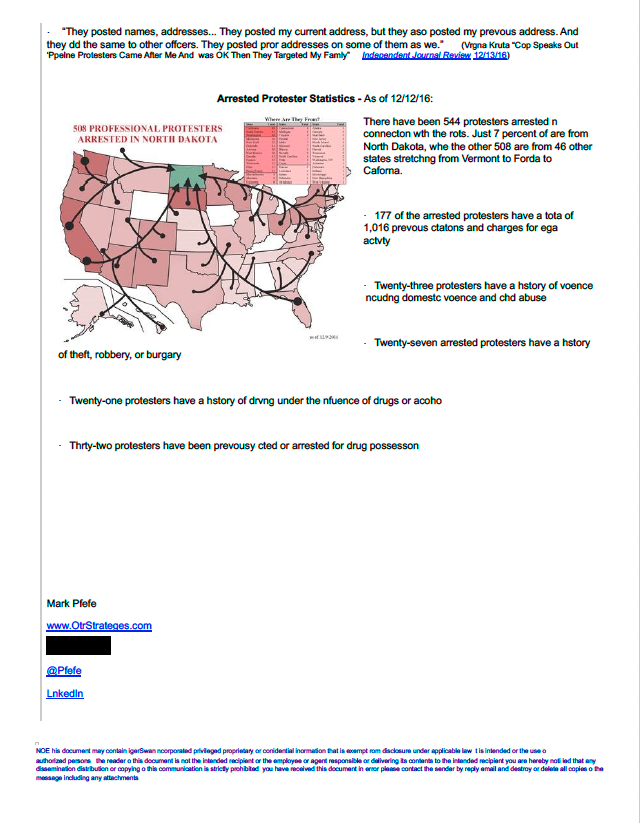

Pfeifle also made summary statistics of protesters’ arrest records and a map of where they were from. The color-coded map came with a running tally of the number of protesters. The details collected by Pfeifle then began showing up in blogs and remarks by police to reporters. One piece by KXMB-TV, a television station in Bismarck, North Dakota, repeated almost verbatim statistics summarizing the number of protesters arrested and their criminal histories, noting that “just 8 percent are from North Dakota.” Neither Delve nor Pfeifle responded to requests for comment.

Naomi Oreskes, a science historian who has researched the fossil fuel industry’s communications strategies, said the attempt to frame environmental defenders as criminals was consistent with a long trend of attempts to discredit activists. However, it was also “particularly noxious,” she said, because the energy industry has pushed for stronger penalties against trespass and other anti-protest laws. “They make it harder for people to engage in peaceful protest,” said Oreskes. “People are arrested and they say, ‘See, those people are criminals.’”

DCI, which got its start “doing the dirty work of the tobacco industry” and helped found the Tea Party movement, was also a key player influencing media coverage, placing op-eds and distributing them. In one exchange between DCI partner Megan Bloomgren, who would later become a top Trump administration official, and Reese, Bloomgren sent a list of 14 articles “we’ve placed that we’ve been pushing over social media.” The articles ranged from opinion pieces in support of the pipeline in local newspapers to posts on right-wing blogs.

Oreskes said using opinion articles this way is a common strategy pioneered by the tobacco industry, among others. “You push that out into social media to make it seem as if there’s broad, grassroots support for the pipeline,” said Oreskes. ”The reader doesn’t know that this is part of a coordinated strategy by the industry.”

MarketLeverage, another Energy Transfer contractor, also spent a considerable amount of its resources tracking social media and boosting pro-pipeline messages. In the weeks following the dog attacks, for instance, Shane Hackett, a top official with MarketLeverage, suggested highlighting a Facebook post by Archie Fool Bear, a Standing Rock tribal member who was critical of the NoDAPL movement. (Neither DCI nor MarketLeverage responded to requests for comment.)

“We need to exploit that shit immediately while we have a chance,” a TigerSwan operative wrote in response to an email from their colleague Rice, the chief propagandist.

Hackett suggested creating creating a graphic out of the tribal member’s post and having “other accounts share his post with the same hashtags.” Rice provided the social media text and hashtags, including, “Respected Tribe Members Call Attention to Standing Rock Leadership Lies and Failures #TribeLiesMatter #NoDAPL #SiouxTruth.” Obscure social media accounts then repeated the exact language.

“These people who are trained to use whatever publicity they can for their advantage, they’re going to do what they want anyway,” Fool Bear told The Intercept and Grist. “They don’t live in my shoes, and they don’t believe in what my beliefs are. If they’re going to take what I say and manipulate it, I can’t stop them.”

Off the Record Strategies and the National Sheriffs’ Association didn’t just focus on issues of law-breaking. The association parroted some of the same messages that TigerSwan — as well as climate change deniers in Congress — were trafficking. Notable among them was a right-wing conspiracy theory that the environmental movement was “directed and controlled” by a club of billionaires.

The National Sheriffs’ Association also tried to undermine the credibility of well-known advocates Bill McKibben (a former Grist board member) and Jane Kleeb, who founded the environmental organizations 350.org and Bold Alliance, respectively. Pfeifle circulated memos on the two movement leaders. “McKibben is a radical liberal determined to ‘bankrupt’ energy producers,” said one, adding, “McKibben will join any protest because he enjoys the fanfare.” Another memo said, “Kleeb admitted her pipeline opposition was about political organization and opportunity, not the environment.”

Kleeb and McKibben expressed bemusement at TigerSwan and the sheriffs’ association’s fixation on their work. “It’s all pretty creepy,” McKibben said in an email. “I live in a county with a sheriff, and it seems okay if he tracks the speed of my car down Rte 116, but tracking every word I write seems like… not his job.”

The sheriffs’ group also listed the nonprofit organizations Center for Biological Diversity, Rainforest Action Network, and Food & Water Watch as “Extremist Environmental Groups” — a pejorative used by some conservative government officials, including from the Trump administration.

“Campaigning against corporations driving our climate crisis and human rights violations is not extremist,” said Rainforest Action Network executive director Ginger Cassady. Brett Hartl, government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said the association’s flyer contained “categorically false” information about the organization — a sentiment repeated by others mentioned throughout TigerSwan’s other records.

“We would urge the Sheriffs’ Association to focus on its own responsibilities instead of attempting to undermine well-meaning organizations like ours,” added Wenonah Hauter, Food & Water Watch’s executive director.

Both the National Sheriffs’ Association and TigerSwan took pride in meddling in tribal affairs. Reese enthusiastically encouraged his personnel to spread a story that the Prairie Knights Casino, run by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, was discharging sewage into the Missouri River Watershed. Meanwhile, the sheriffs’ association worked with TigerSwan to push a story about a drop in revenue at the casino. In an email to TigerSwan’s Rice, Pfeifle noted that the issue had been raised at a recent Standing Rock tribal council meeting.

“We moved this story on front page of Sunday Bismarck Tribune and in SAB blog Friday, playing perfectly into the ‘get-out’ narrative going into next week,” Pfeifle wrote to Rice a few days later, referring to the conservative Say Anything Blog. “Please help echo and amplify, if possible.”

Using newsletters and news-like web sites to discredit pipeline opponents’ concerns as “fake news” was a top tactic for both TigerSwan and the National Sheriffs’ Association. The irony of the strategy was not lost on its protagonists.

Over WhatsApp, in June 2017, Rice, the propagandist, chatted with Wesley Fricks, TigerSwan’s director of external affairs, about a possible response to a Facebook video in which an unnamed reporter described recently published news reports on TigerSwan’s tactics. They would post it on one of the astroturf sites Rice created and describe it as “fake news.”

“That will cause a few people’s brains to explode,” Rice wrote in a WhatsApp message. “fake news calling fake news fake which is calling other news fake?”

Frick replied, “One big circle.”