Hello, and welcome to the first edition of Record High, a limited-run newsletter about extreme heat. I’m Jake Bittle, a reporter here at Grist, and for the rest of the summer my colleagues and I will be exploring what happens when the mercury rises — who is impacted the most, how it ties in to climate change, and what communities can do to cope.

When climate reporters talk about global warming, we often warn readers that the Earth’s temperature could rise by at least 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius (2.7 to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) over the course of this century. That might not sound like a lot — you wouldn’t notice if the temperature in your living room went up by that much — but just 1 degree C of global warming makes local heat waves much worse and much more frequent. In fact, heat is perhaps the extreme weather event with the strongest link to climate change. Scientists are now comfortable assuming that all heat waves are being made more severe or likely because of climate change.

The reason is that as global temperatures rise, they dry out soils and heat up ambient air. They may even slow down the jet stream that circulates the globe, and make it wobblier. As my colleague Joseph Winters explains in a feature published today on Grist, all these shifts make it easier for high-pressure air systems to develop, park over land, and create devastating hot spells on the ground.

That’s what happened in the Pacific Northwest during the summer of 2021, when a heat dome pushed temperatures into the triple digits for almost a week, killing more than 800 people across Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. In later attribution studies, scientists found that climate change made the disaster hundreds of times more likely. Researchers estimate that another 1 degree C (1.8 degrees F) of warming could turn the Pacific Northwest disaster into a once-in-a-decade affair.

“You can be confident that heat waves are increasing everywhere globally due to climate change,” Sarah Kew, a climate researcher at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, told Joseph.

Extreme heat is also rarely just heat. These hot spells can have a compounding effect, making other climate disasters more frequent and more dangerous. Marine heat waves, which have become more common over the past decade, may contribute to stronger hurricanes, and high heat is also a key ingredient in tornadoes and severe thunderstorms that cause lethal flooding. In other parts of the world, heat waves often exacerbate drought, drying out earth and plants by increasing “evaporative demand,” and a drier landscape can lead to more wildfires. A period of extreme heat can create a ricochet effect across an entire region.

Scientists are now comfortable assuming that all heat waves are being made more severe or likely because of climate change.

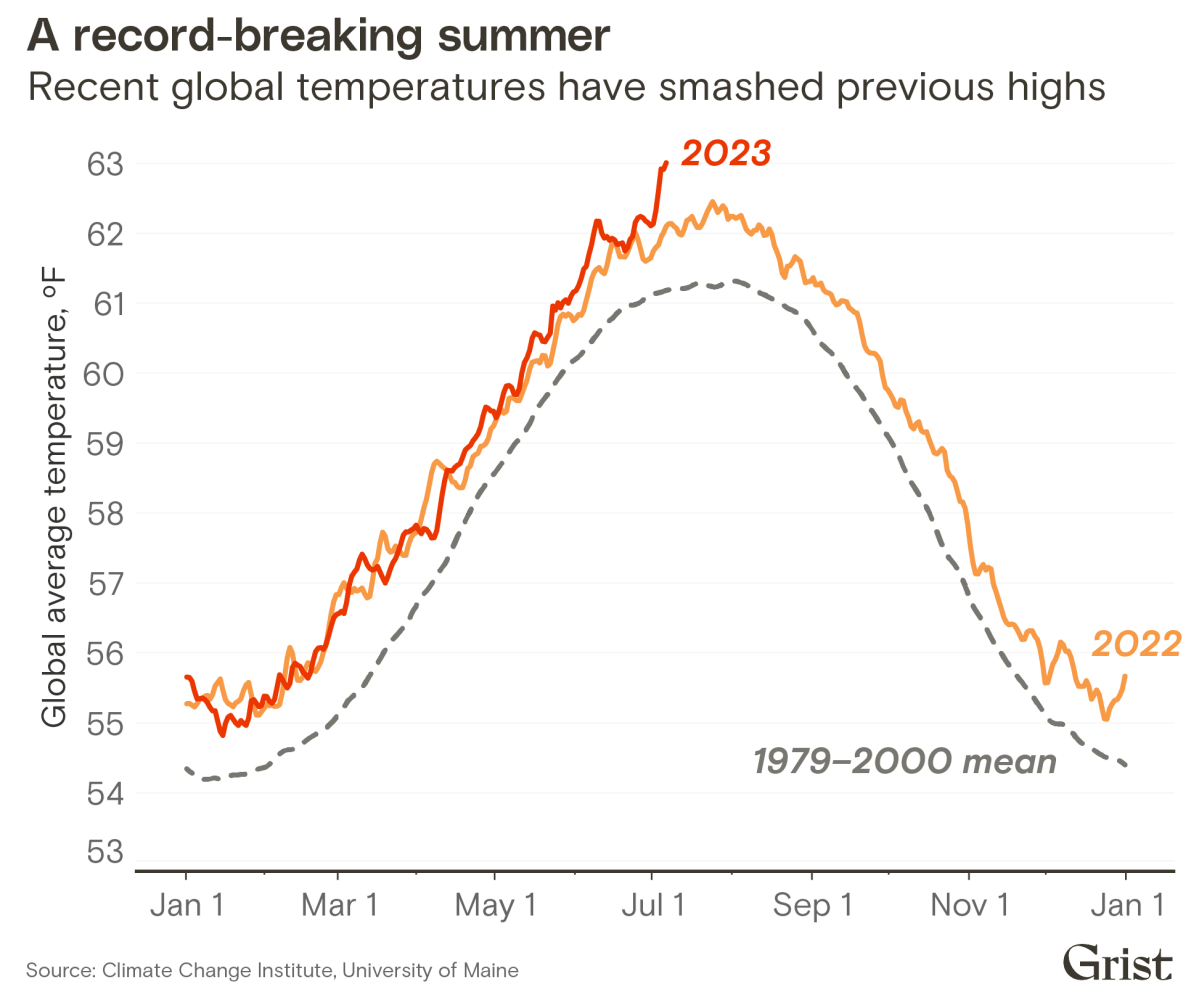

This past week saw the seven hottest days in recorded history, and already this year there have been deadly heat waves in India, Mexico, and the Southern United States. This is all happening before the full reemergence of the El Niño climate pattern, which will raise global temperatures even more over the coming year. These heat waves endanger young children, elderly people, and outdoor workers, and they also threaten key infrastructure like roads and power lines.

To learn more about the science behind extreme heat, read Joseph’s full story. And keep an eye on your inbox for next week’s issue of Record High.

By the numbers

Last week was the hottest in recorded history, as global average temperatures soared above 17 degrees Celsius for seven straight days. The previous hottest day on record, in August 2016, also coincided with an El Niño event. My colleague Akielly Hu reports more on this record-breaking streak here.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

What we’re reading

A new book about extreme heat: Grist’s Zoya Teirstein interviews Jeff Goodell, a Texas-based climate journalist and the author of The Heat Will Kill You First. Goodell’s new book, published today, explores the terror of “life and death on a scorched planet.”![]() Read more

Read more

Heat waves cause increased flaring: Texas oil and gas operators flared and vented hundreds of thousands of tons of methane gas during this month’s heat wave, according to Inside Climate News. The flaring will contribute to the buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. ![]() Read more

Read more

Protecting farmworkers from deadly heat: A nurse in Florida is educating farmworkers to listen to their bodies while on the job, in an effort to teach workers to recognize early signs of heat stroke and heat exhaustion, the Washington Post reports. ![]() Read more

Read more

How renewables bailed out Texas’s grid: Texas Monthly writes that record solar power generation may have saved the Lone Star State’s troubled energy grid during a recent episode of extreme heat. The state’s ample solar and wind infrastructure helped meet record demand even as coal and gas plants faced outages. ![]() Read more

Read more

Are extreme heat plans enough?: Many cities in the United States have developed plans for coping with big heat waves, but the AP reports that these plans often aren’t sufficient to protect vulnerable populations, since they don’t address structural inequalities in how cities are built.![]() Read more

Read more