Cross-posted from the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Rob Steuteville has posted a terrific analysis on the New Urban Network rebutting the claim by the National Association of Homebuilders (NAHB) that “the existing body of research demonstrates no clear link between residential land use and greenhouse-gas emissions.”

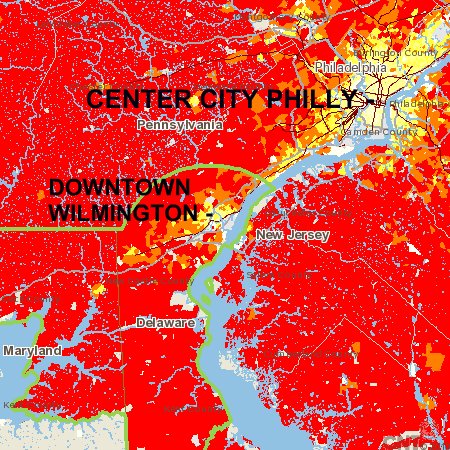

Rob responds with Todd Litman’s excellent research and writing [PDF] on the subject, along with the great mapping from the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT) of CO2 emissions per household for every metro area in the U.S. As Rob points out, CNT’s research shows a very consistent geography in just about every region: The farther out one goes from downtowns and strong suburban centers, with their superior central locations and neighborhood characteristics, the greater the miles driven and carbon emitted per household.

Image: Center for Neighborhood Technology

Image: Center for Neighborhood Technology

I’m headed to a conference later this month in Wilmington, Del., so I pulled CNT’s emissions map of the region containing Wilmington. The areas in red on the map above basically have two or more times the per-household transportation emissions of the areas in light yellow.

Image: Center for Neighborhood Technology

Image: Center for Neighborhood Technology

Just for illustration, we can see that a very similar pattern holds for metro Phoenix, an area most of us would consider to be dissimilar to Wilmington.

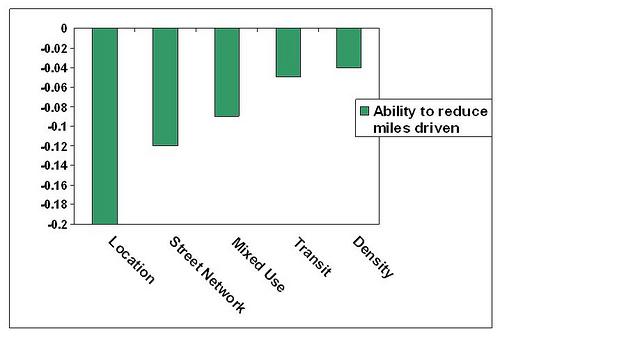

Rob writes that the flaw in NAHB’s analysis is that they looked only at the density of residential development, in isolation from other relevant factors:

If all you do is bring people closer together, you get modest reductions in gasoline consumption. But if you do all of the other things associated with smart growth — that is to say, create a walkable environment with multiple destinations and alternative modes of transportation — the impacts on vehicle miles traveled, energy use, and greenhouse-gas emissions are huge.

That is true as far as it goes, but I would go further to clarify the most important factor of all is what transportation researchers call regional accessibility (sometimes also called “destination” accessibility), or the location of a place within a region. The more central a place is to the region, or to a strong suburban center, the lower the vehicle miles traveled, in large (though not exclusive) part because driving distances become shorter.

In Ewing and Cervero’s exhaustive study of the published literature, they found that such locations are as significant in reducing driving rates as the next two significant factors (street connectivity and mixed land use) combined. (See graph above comparing the significance of five major factors.) As Todd Litman puts it, “residents of more central neighborhoods typically drive 10-30 percent fewer vehicle miles than residents of more dispersed, urban fringe locations.”

This is why smart growth favors infill and redevelopment and disfavors new greenfield development on the fringe of a region. It is also a principal (though not the only) reason why those CO2 maps show such lower emissions rates in the centers of regions. I sometimes make a point to mention the importance of location because it can get lost in discussions among designers. It is especially critical to understand when we start discussing concepts such as the oxymoronic “agrarian urbanism” — a type of development that, if pursued improperly, could lead to greater dispersal of development across regions, and consequently to increased emissions.

Street connectivity, by the way, is the strongest indicator of how much walking takes place in a neighborhood. Many thanks to Rob for taking this on.