The Diffleys in the early days of Gardens of Eagan. (Photo by Helen De Michiel.)

Books written by farmers are rare — and for good reason. Growing food takes a lot out of you, and most farmers have little or no time to reflect on their lives or package them up for an audience.

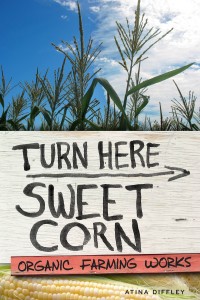

But the fact that it’s written by a veteran organic farmer is only part of what makes Atina Diffley’s book Turn Here Sweet Corn unique. Part memoir, part chronicle of the evolution of the upper Midwest organic movement and the corporate forces exerting pressure against it, the book also allows new farmers to hear from someone who has spent time in the trenches. Diffley, who co-founded the Gardens of Eagan, a successful Minnesota organic farm which has served the Twin Cities region for nearly three decades, comes across first and foremost as a survivor. She writes passionately about the years she and her husband Martin spent farming and raising a family, in the face of a seeming avalanche of challenges. Diffley takes readers along as they faced devastating droughts and hailstorms (with hailstones “as big as size-B potatoes”), razor-thin margins and near bankruptcy, and an unexpected eminent domain eviction from their first farm.

Then, near the end of the book, the couple hit against the biggest challenge of all: the threat of a Koch Industries pipeline tearing through the middle of their second farm. And rather than take it lying down (and losing the soil they’ve been building for years), Diffley takes on one of the biggest oil companies in the world, organizes the Twin Cities community, and succeeds at not only protecting her own farm, but convincing the area’s public utilities commission to protect and value all organic farmland in the area.

We spoke to her recently about farming, writing, and the struggle to protect organic land.

Q. Who did you want to reach with this book?

Q. Who did you want to reach with this book?

A. I wanted to write a book that would bring in new audiences, not just people who were already engaged. Because whether you farm or not, everyone has a relationship with land through their food. So many people don’t realize the food choices they make have a big impact on land somewhere. And by impacting land, they’re impacting the species that live on that land or in that community. And once they understand that, there’s so much they can do.

We hear a lot of people talk about protecting wilderness, but most people don’t realize that there isn’t much actual wilderness anymore; most land is in use. Their choices, and largely their food choices, have huge impacts on the environment. It’s not that complicated. I see three main areas of responsibilities: eating to protect the earth, educating others, and then engaging in policy.

Q. That third part is the hardest for most people.

A. Yeah, that policy piece is so crucial. Look at Europe, where they have always had strong policies to support and promote and transition land to organic. Well, there are many countries in Europe where more than 20 percent of their land in agriculture is organic. In the U.S. we’ve had a marketing approach, and the USDA isn’t willing to say that organic is any better; they say it’s just a different marketing option, so more like 4 percent of our food is organic and less than 1 percent of land is.

One thing I learned while we were fighting the pipeline is that it’s your legislator’s job to listen to their constituents. So they absolutely have the right to go in and speak with them at any point.

I learned about informed citizen input versus public clamor. In our pipeline case, 4,800 people wrote letters to a judge. They didn’t just yell and stomp their feet; they politely and respectfully explained to the judge how organic farming systems are different, and how they would be lost [if a pipeline was dug].

Th Diffleys watch a bulldozer tear up their first plot of land. (Photo by T. L. Gettings for Rodale Institute.)

Q. You write about losing your first farm to development — what did that teach you that prepared you to fight the pipeline?

A. The development of the 120-acre farm [had] happened in sections over a period of five years. Then all life — the trees and grasses, the flowers and forbs, the fruit and bushes — was torn out, and burned or buried. Even the living topsoil was scrapped into a pile and sold off. The remaining subsoil was flattened and reshaped.

We continued to farm on the land that had not yet been developed, immediately adjacent to land that had been stripped of all life, but it was an ecological disaster. Rain could not soak into the adjoining land; there was no life to hold water, and it ran off into our fields. After a heavy summer storm our potato field was covered with 14 inches of silt and gravel. Pests and disease — previously a non-issue — became a losing battle.

After the development experience I was not willing to allow a pipeline through here. But it was pretty scary to think of taking on the largest privately owned company in the world, and everyone said, “You cannot move a pipeline.”

Shortly after receiving the letter informing us of the pipeline route I went online and found the Agricultural Impact Mitigation Plan [for the pipeline]. When I came to the part where it read: will not knowingly allow the amount of top cover to erode more than 12 inches from its original level — I no longer had any option.

Nature should have legal rights of its own, but it doesn’t. To protect nature in our courts of law it is required to show a loss to humans, so humans have to stand up and speak for it.

Q. I know you and your husband now do organic consulting and education. Are you still farming?

A. The farm is being managed by Wedge Community Co-op, who purchased our name in 2008. They have a farm manager. After this season they’ll be moving to a new plot of land and Martin and I will have our land back to farm again. We’ve had a five-year break. We’re going to move the farm into a more permaculture-type setting, with grasses, fruits, and perennial crops. It’ll be less demanding and less taxing — for us and the land.

Q. Do you want to talk about your process of writing the book?

Atina and Martin Diffley today. (Photo by Greg Thompson).

A. It was one of the healthiest things I’ve ever done for myself. We had never really had time to go back and deal with the emotions around [losing our first farm to] development. At the time we had a new farm to start, and children to raise.

Before I started writing it I would have described myself as having anger management issues. Now it’s completely gone. I reevaluated everything while I was writing and most of the anger just disappeared.

A lot of writing romanticizes farming and a lot of writing is cynical about it. I think the truth is somewhere in the middle.

Seventy-five percent of Midwestern farmland is going to change hands in the next 15 years. And I heard someone say recently — when talking about beginning farmers — that we “have to romance them.” At the time I thought, “It’s not romantic. It’s hard work! Why trick them into thinking it’s romantic?” But then when I was writing the book I suddenly saw what was really romantic about farming. And I could see so clearly that there is really no other life I would have ever wanted to live. It’s incredibly romantic to be able to choose the life that you want.