When you hear about bots in the news, it’s usually something bad. Bots, bits of software designed to perform routine tasks for their human creators, are often associated with scam calls, fake social media accounts, or spreading disinformation, even though most are relatively benign, like chatbots.

But there’s a new kind of bot out there, and it’s trying to raise the alarm about the climate crisis, one click at a time. Two New York City-based artist-engineers started a project called Synthetic Messenger, a botnet (short for “robot network”) that visits articles about the overheating planet and increases their visibility by clicking every single ad on the page. The thinking behind it is that all these clicks (called “engagement” in industry-speak) send revenue to news outlets, encouraging more climate coverage. Over the course of a week and a half earlier this month, the bots visited 2 million climate articles and clicked on 6 million ads.

Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, the duo behind the project, say they’re trying to draw attention to how online algorithms are altering perceptions of the climate crisis — and how the news cycle influences the carbon cycle.

Bots have been playing a role in spreading fake news about global warming. During the horrific bushfires that started burning in Australia in 2019, for instance, an analysis found that bots and trolls had exaggerated the role of arsonists, downplaying the link with climate change.

Compounding the problem is that an article’s prominence is getting determined by these “rapidly changing black-box algorithmic systems,” said Brain, an assistant professor of digital media at New York University. Ads about the “Global Warming Hoax” have ended up at the top of Google search results, tailored to an individuals’ search history. YouTube’s algorithms have been accused of promoting climate denial videos in its “up next” feature, sending people down a misinformation rabbit hole.

Another issue is that much of the mainstream media relies on revenue from page views and ad clicks to keep their operations humming. And climate change has been called a “ratings killer” — not exactly “click-worthy.” Though there are plenty of ways to make such articles engaging, that stigma can lead to less coverage of our planetary predicament. “Questions about engagement, clicks, and ad revenue — they certainly do contribute to editorial decisions about what topics are covered, how they’re covered, and how stories are promoted,” said Lavigne, an artist and educator in New York.

Lavigne said that Synthetic Messenger is more about making an artistic statement than offering a realistic solution to the problem — though if the project was scaled up, he supposed, “it could shift the needle in some sense.” For him, it’s a way to highlight the problems with how people get information online, “towards the ends of disrupting a power system or undermining it, rather than propping it up.”

Bots are everywhere online, often performing tedious tasks, yet Brain said that they’ve become “the straw man for a lot of political issues in the U.S.” (Are bots really responsible for “poisoning democracy,” or are other factors at play?) Lavigne said that Synthetic Messenger is a response to this overblown discourse, a way of “demystifying” bots. Earlier this month, they hosted a creepy Zoom-call-turned-art-project featuring livestreams of what each of the 100 bots was up to on their computer screens. Brain and Lavigne used images of volunteers’ hands and recordings of them saying “scroll” and “click” to illustrate what the bots were doing as they paged through the articles.

“Just to be clear, there’s no reason that these bots need to do anything visual at all,” Lavigne said. “I think part of what was fun about this as a performance was to think about a way to show the audience what was happening.”

It’s not Lavigne’s first foray into experimenting with Zoom performance art. He also invented a tool called Zoom Escaper that helps you escape from videoconference meetings by self-sabotaging your audio, “making your presence unbearable to others” by adding an annoying echo, construction noise, or the sound of a crying baby in the background.

Brain and Lavigne put some safeguards in place to make sure that the Synthetic Messenger bots are not clicking on articles that promote straight-up climate denial — you know, the idea that warming temperatures are the result of solar radiation or whatever. They have a “denial list” blocking certain sites, including ones owned by Rupert Murdoch.

It’s unclear who’s behind the climate-denying bots, but there are some obvious suspects. The field of public relations has been closely linked with oil companies for more than a century, with spinmasters helping the industry downplay misdeeds, twist facts, and cajole the media into repeating their talking points. In the spring of 2017, when former President Trump announced the United States would withdraw from the Paris Agreement, an analysis found that one-quarter of all tweets about climate change were generated by bots. The study’s authors speculated that the bots were probably the work of fossil fuel companies, petro-states like Saudi Arabia, or the public relations agencies that work for them.

“The fossil fuel industry for a long time has known that if you can control the narrative, you can influence the carbon cycle,” Brain said.

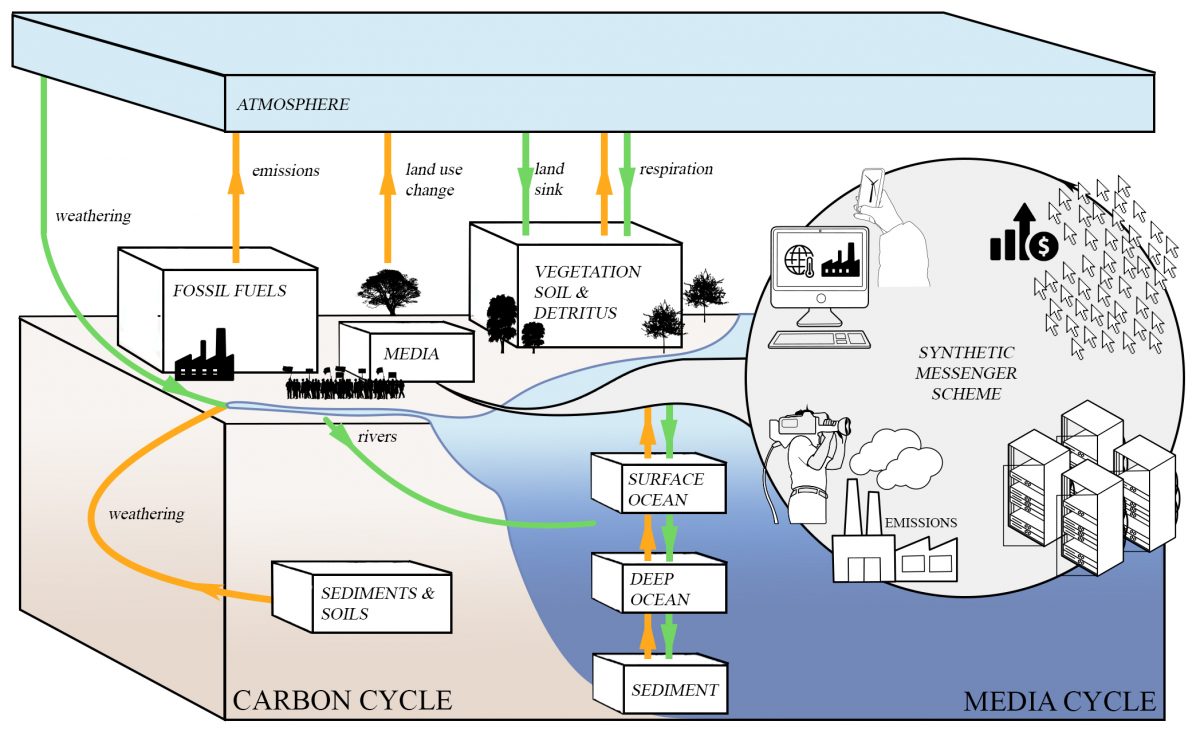

The classic image of the carbon cycle, which shows how carbon dioxide flows around the planet through photosynthesis, decomposition, respiration, and combustion, “leaves so much out” in terms of the influence of culture and politics, Brain said. Synthetic Messenger offers an alternative version that puts the news media in the picture, sandwiched between fossil fuel emissions and carbon sequestration from plants and soil.

The Synthetic Messenger bots are on pause for now — the project was intended to be a performance for a Dutch arts festival this month exploring society and technology. But Lavigne said that the bots may get a reboot in the future, either as part of another performance or a longer-term effort.

Brain and Lavigne see the media manipulation practiced by their bots as a form of “climate engineering,” a term that normally refers to large-scale schemes to dim the sun or suck carbon dioxide out of the air.

“At a time when our action or inaction has distinct atmospheric effects,” the Synthetic Messenger site reads, “the news we see and the narratives that shape our beliefs also directly shape the climate.”