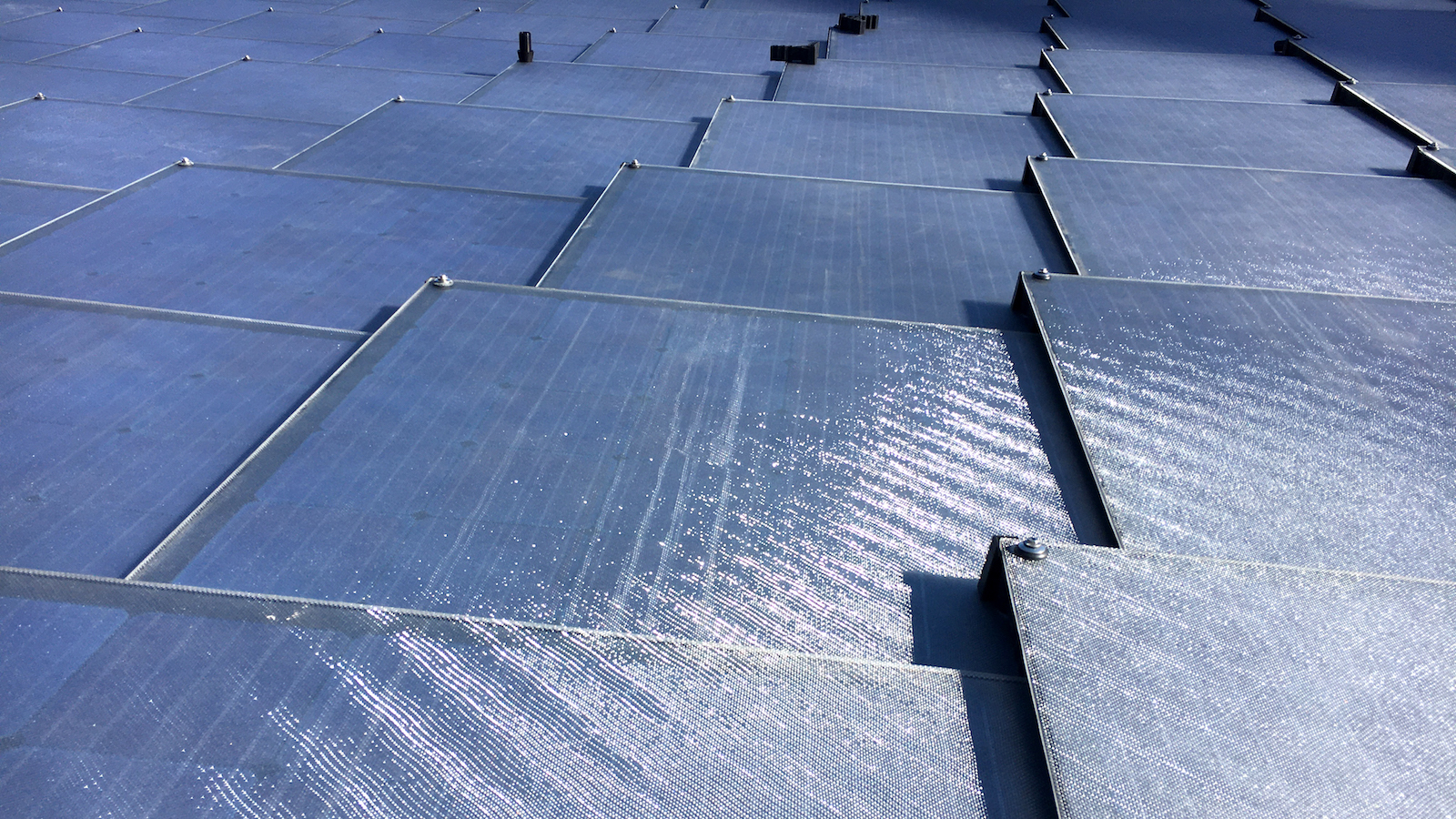

Google’s newest office buildings in Mountain View, California are covered in silver scales. Some 90,000 squares ripple across four rooftops, near the tech giant’s headquarters, each overlapping slat a solar panel. Once operating next year, they should be able to meet roughly 40 percent of the four buildings’ electricity needs.

These “dragonscale” rooftops are perhaps the most eye-catching example of Google’s larger climate goals, which involve using only carbon-free energy at its nearly two dozen data centers and 70 offices worldwide by 2030. Google says the unique installations might do more than limit emissions at its new Bay View and Charleston East offices. They could also pave the way for buildings across the country to adopt the reptilian design — if dragonscales can overcome the same barriers in the way of other novel solar technologies.

The idea is “to kickstart this market in the U.S. by showing it can be done,” said Asim Tahir, who leads Google’s renewable energy strategy, in an interview with Grist. The four solar arrays will have a combined installed capacity of 7 megawatts, or enough to power roughly 1,800 average homes in California.

Google’s initiative arrives as engineers and building developers worldwide are trying to transform homes, offices, and factories from energy hogs into energy-efficient properties. In 2019 — before the pandemic disrupted office life and everything else — buildings churned out a record level of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions, accounting for 28 percent of the global total, according to the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction. Residential and commercial buildings continue drawing electricity from carbon-intensive grids and burning natural gas for heating and cooking.

Workers at Google’s Bay View campus in Mountain View, California, install “dragonscale” solar shingles during the summer 2021. The shingles have a unique prismatic surface and overlap in a diamond design. Photos by Chris McAnneny / Heatherwick Studio

To curb emissions, many companies are installing LED lighting systems in their offices, adding thick insulation panels made of wood and styrofoam and, as Google is doing, building geothermal systems that store heat underground to warm buildings and water supplies from the bottom up. A much smaller number of properties use “building-integrated photovoltaics,” which embed solar cells into the actual roof tiles, windows, or façades. Google’s dragonscale shingles don’t sit atop the canopied roof; they’re part of the roof itself.

“We need to cover every surface that can take solar panels with solar panels,” Tahir said.

U.S. solar firms have been trying to do just that for more than a decade. Yet despite rising interest from homeowners and commercial building owners, building-integrated solar technologies have struggled to achieve anything close to the mainstream success of conventional solar panels mounted on rooftops or arrayed on the ground. Of the more than 3,000 megawatts of residential solar installed in 2020, roughly 1 percent were solar shingles, according to Paula Mints, who runs the global solar research firm SPV Market Research.

A key reason is cost. Today, solar shingles are made in limited amounts by specialized manufacturers, and installing them requires a specialized labor force. Such constraints recently led Tesla to hike the price of its Solar Roof projects by tens of thousands of dollars, in some cases. By contrast, with a typical silicon solar panel, all the raw materials and components are produced in high volumes in giant factories, mainly in China. Installing panels is by now a relatively easy, inexpensive task that happens thousands of times a year.

Another challenge for solar shingles is that they’re generally less efficient at turning sunlight into electricity. This is primarily a problem with heat. As the silicon solar cells inside panels or shingles heat up, they gradually produce less power. Panels can be elevated slightly off the rooftop, allowing air to circulate and cool them down, but shingles are often tightly knitted together with little air flow.

“Because they’re integrated into the roof, they usually get very hot and typically produce 20 to 30 percent less electricity than an average solar panel would,” said Vikram Aggarwal, CEO of EnergySage, an online marketplace for solar arrays. This also means shingles generate less solar power during the sunniest, hottest time of the day. As a result, it costs significantly more to generate a kilowatt-hour of power with building integrated solar versus a typical residential array, he said.

Both Aggarwal and Mints said it was too early to tell how Google’s dragonscales compare to other solar technology, or how they might compete in the U.S. solar market. The tech giant has disclosed few technical details, and the shingles won’t start fully producing power until the California installations are completed next year.

But the dragonscales have at least one obvious advantage: They can carpet the sloping segments of Google’s roofs in ways that standard roof-mounted panels cannot.

The tops of Google’s new offices in Mountain View — which, to make another reptilian comparison, resemble turtle shells — feature long glass cut-outs that allow as much natural light to enter as possible without turning the buildings into sweltering greenhouses, Tahir said. Google engineers designed solar arrays to cover the remaining parts of the roof, building miniature versions in their own lab and consulting with outside solar manufacturers, including the Switzerland-based company SunStyle.

At the heart of a dragonscale shingle is a standard silicon solar cell. Everything else is unique. The cells are kept beneath a layer of highly textured “prismatic” glass, which Google claims can trap light particles within the solar shingle that would escape from a traditional flat panel. The shingles are covered with a specially developed anti-glare coating, keeping them from blinding pilots landing at a nearby federal airfield. The solar shingles are also arranged using SunStyle’s overlapping diamond configuration, to keep wind, rain, and ice from slipping through the cracks.

SunStyle itself has installed similar-looking arrays on more than 500 roofs in Europe and two properties in the United States: First Equity Bank in Skokie, Illinois, and an architect’s house in New York’s Hudson Valley. The 14-year-old company says it’s now launching a more affordable, ready-made version of dragonscales for the U.S. mass market.

Jessie Schiavone, CEO of SunStyle North America, said the company will initially market their panels to homeowners who are planning to replace their roofs and also want to install solar. A solar-shingle roof should cost about the same as a new typical roof with panels mounted on top, except that the solar shingles will be able to cover more surfaces, like eaves and ridges.

It won’t hurt that Google’s buildings are essentially billboards for the shimmering, power-producing roofs. Mints of SPV Market Research said that with other premium solar technologies, including Tesla’s Solar Roof, aesthetics and brand association are often just as important considerations as cost and solar power production — at least for customers who can afford it. “What you really have is a cool-looking roof market,” she said.