Corporations churn out single-use plastic packaging by the truckload — disposable yogurt cups, takeout food containers, shopping bags, mailers, cling wrap, and more. These items comprise much of the 19 million metric tons of plastic waste that ends up in the environment each year. As such, many companies have made vague promises to address the plastic pollution crisis by increasing the recyclability of their packaging and reducing the amount of virgin material they use.

But they’re not doing enough.

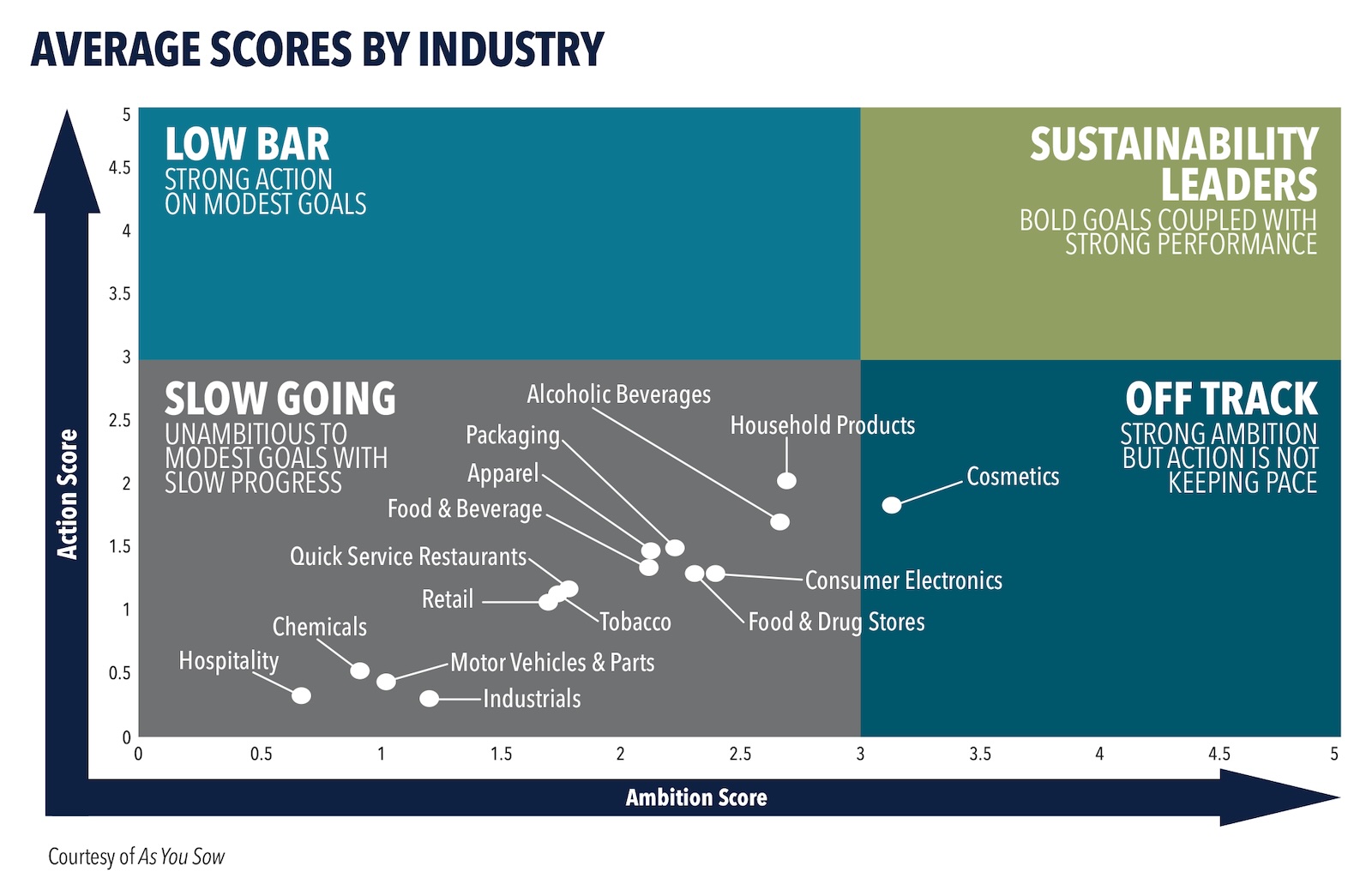

According to a new analysis published Wednesday by the shareholder advocacy nonprofit As You Sow, dozens of the world’s largest companies are falling short on both ambition and action to ensure plastic packaging doesn’t end up in landfills or littering the environment. Too few companies have quantitative sustainability targets for plastic, the report says, and those that do are either setting the bar too low or are failing to make significant progress — or both.

“Every company can be doing more,” said Kelly McBee, circular economy manager at As You Sow and one of the report’s co-authors. In particular, she said corporations should place more emphasis on reducing the plastic they use, rather than replacing virgin plastic with recycled content.

For its report, As You Sow looked at annual reports, sustainability reports, filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission, and other publicly available resources from 225 of the world’s most valuable companies across five sectors: apparel, food and beverage, household products, quick-service restaurants, and retail. The nonprofit evaluated these corporations on six criteria related to advancing a “circular economy for plastic packaging,” referring to a system that keeps plastic in use for as long as possible before it has to be thrown away.

These criteria included the recyclability of companies’ plastic packaging, whether that packaging is made from recycled material, and how much of it is reusable. The report also considered companies’ efforts to reduce plastic use and support extended producer responsibility, or EPR, policies that would make them financially responsible for managing their plastic packaging after it’s sold to consumers.

Each company got scores for overall ambition and overall action, which, combined, contributed to a letter grade. Measurable steps were weighted more heavily than targets “to elevate the importance of action over words,” as McBee put it.

No company got an A, and only nine got a B. Half got an F, and almost every industry was characterized by “unambitious to modest goals” with “slow progress” toward achieving them. The industries with the highest average scores were cosmetics, household products, alcoholic beverages, and consumer electronics. Those at the bottom were hospitality, chemicals, and motor vehicles.

It’s not the first time As You Sow has brought scrutiny upon companies that contribute to the plastics crisis. Previous reports in 2020 and 2021 ranked a smaller cohort of companies on their commitments to sustainable packaging and found similar shortcomings on reuse, data transparency, and financial contributions to waste management infrastructure.

In its most recent report, As You Sow also found that few companies had a quantitative, time-bound target for switching to reusable packaging, although many had pilot programs. And of the 147 companies with a package recyclability goal, only 15 percent were on track to meet it.

These findings line up with what some other groups have found about the gap between companies’ plastic promises and their actions. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for a circular economy, reported last year that corporations that had signed on to its “global commitment” to advance plastics circularity had collectively made no progress to reduce virgin plastic use since 2018.

Other analyses have suggested that most large companies are off course to meet self-imposed targets for plastics recycling by 2025.

Melissa Valliant, communications director for the nonprofit advocacy group Beyond Plastics, said these findings are in some ways unsurprising. “Historically, goals from the largest consumer goods companies have served as pretty PR stunts that generate headlines and reassure the public,” she told Grist. She said As You Sow’s findings emphasize the need for government regulation — not just voluntary corporate commitments — to expedite companies’ progress.

Of all the ways companies can make their plastic pledges more credible, McBee says her top recommendation is that they think beyond goals to reduce just their virgin plastic use, referring to plastics that are made directly from fossil fuels. Companies with such a goal tend to replace their virgin plastic with recycled material — a swap that may increase circularity, but does not address what As You Sow calls “a key driver of pollution”: the overuse of plastic.

Instead, As You Sow calls for companies to decrease their “plastic use intensity,” or the amount of plastic used for each dollar of revenue. This might be accomplished by redesigning packaging to have less surface area or thinner plastic layers, or by eliminating unnecessary types of plastic packaging.

Notably, reducing plastic use intensity is not the same as reducing net plastic use. If a company produces a lot more of a given product, its overall use of plastic packaging could grow even if it’s making less plastic per dollar earned. This is essentially what has happened with Coca-Cola, which said in its most recent sustainability report that it had “avoided half a million metric tons of virgin plastic” in 2022 but increased its total virgin plastic use due to “growth of plastic packaging.”

McBee said absolute reduction targets would be ideal, but that intensity targets can give more flexibility to growing businesses. This is a position that is perhaps informed by As You Sow’s status as both a shareholder and an advocate. The organization buys shares in major companies and uses them as leverage, either to negotiate directly with executives or to file resolutions on environmental practices. As an advocacy group, As You Sow wants companies to adopt the most robust environmental policies; as a shareholder, McBee said As You Sow is “financially invested in the success of these companies.”

Valliant, with Beyond Plastics, pushed back on the idea of plastic intensity targets and called for “a solution that doesn’t bring more plastic into our lives and the planet and our bodies.”

“At the end of the day,” she told Grist, “we need less plastic overall.”

Either way, both McBee and Valliant agreed that companies should be investing more in reusable packaging and packaging-free product formats — for example, concentrated soap tablets that don’t need to come in a plastic bottle. Valliant said the need to prioritize reusable over recycled packaging is especially urgent given research suggesting that recycling plastic increases its toxicity.

As You Sow’s other recommendations for companies include eliminating toxic chemicals from plastic products, phasing out or dramatically reducing the use of flexible and multilaminate plastic packaging (like the plastic used in bags of potato chips), and making financial contributions to recycling infrastructure that are commensurate with the amount of plastic packaging they produce. To incentivize some of these measures, the report suggests that companies align CEO compensation with key benchmarks for circularity. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, some companies like Mars and Coca-Cola are beginning to do this.

If the environmental costs of inaction on plastics aren’t persuasive enough, then perhaps the legal, regulatory, and reputational ones are. By failing to act more aggressively, companies may be exposing themselves to investigations and lawsuits from state attorneys general and to increasingly common bans and restrictions on whole categories of plastic. Plus, there’s the United Nations’ global plastics treaty, which environmental advocates are hoping will place a cap on the amount of plastic the world produces annually.

Stronger action on plastics can also appease consumers. According to McBee, customers are increasingly connecting the “ambiguous” issue of plastic pollution back to individual companies that are responsible for it. “They’re going out of their way to support the companies that are making a difference,” she said, “and facilitating the creation of the world they want to live in.”