Marcin WicharyYou can’t go here anymore.

Yesterday The New York Times explored the problem of beachfront access in its “Room for Debate” series. The impetus for the discussion is a controversial move by Vinod Khosla, the Silicon Valley venture capitalist, to close off public access to a beach on the San Francisco peninsula after buying a 53-acre tract along the Pacific coast.

Khosla, who cofounded Sun Microsystems, is known for financing disruptive technology — his former firm Kleiner Perkins helped kickstart Google and Amazon, and he went on to become an investor in ethanol biofuels, “clean coal” technology, and other cleantech. But his Martin’s Beach purchase raised issues about what happens when privatization disrupts leisure activities that hitherto were open to the public. Surfers who frequented Martin’s before Khosla closed it off with armed guards are suing him over beach access. The legal battle has fomented social tension around private ownership versus public trusts, environmental considerations versus economic, and even the racial and class implications of beach privatization.

I’ve written about some of these tensions recently:

- This piece, exploring how the racial segregation of pools and beaches might explain some African Americans’ fears of swimming.

- This Memorial Day post, on how African-American members of the military descended upon France’s beaches on D-Day to fight for freedom during World War II, only to return to segregated beaches and Jim Crow facilities here at home.

- And this interview with historian Andrew Kahrl, whose book The Land Was Ours: African American Beaches from Jim Crow to the Sunbelt South explains how an American kleptocracy stole coastal land directly from black Americans throughout the 20th century.

Kahrl is one of the four experts The New York Times plucked to debate the beachfront access problem. And, as in his book, he did not shy away from the racial and environmental implications of beach privatization:

During the Jim Crow era, whenever a southern beachfront was “discovered” by developers, outright racial segregation and African-American exclusion soon followed. … That building boom enveloped and disfigured low-lying coastal areas across the U.S. Indeed, much of the environmental damage inflicted on beaches over the years has been done in the interest of protecting property values and enhancing coastal commerce.

It’s worth pointing out that the bigotry that sometimes lies behind blocking beach access isn’t always racial. It can also be class-based. Khosla is not a white American from the Jim Crow South. He was born in Delhi, India — in a country that has its own serious issues with class discrimination.

But as Kahrl’s book points out, African Americans were not immune to the seduction of class-based exclusion either. Some black people were able to accumulate wealth throughout the mid-20th century, but couldn’t move away from red-lined, ghetto residences. Government policies forbade them from living in many areas. When wealthy black Americans were able to buy coastal areas and beachfront properties, it was often to escape not only Jim Crow but also the suffocating poverty of black neighborhoods.

“[P]ossession of valuable property — and fear of losing it — accentuated and hardened class divisions among black Americans and gave rise to a defensive property politics that until now historians have almost exclusively examined through the lens of white suburbia,” wrote Kahrl in his book.

But Khosla argues that this is just a basic private property rights case. He doesn’t live on the Martin’s Beach property and said during trial that he has no plans for it either. Yet he has a gate around his land that is meant to keep the public out. “If you’re asking me why any gate is locked, it’s to restrict public access,” said Khosla during court testimony. He believes he has the right to keep out who he wants, which at best suggests an ignorance of the race and class historical contexts of such exclusion in America. It also ignores the rights of taxpayers.

“Much of the nation’s coastlines have been shaped by federal, state and local dollars,” wrote Coastwalk California’s Una J. M. Glass in the NYT debate. “Government-funded stabilization and sand replenishment projects have kept many beaches from disappearing and national flood insurance has allowed homeowners to feel secure about investing in waterfront properties.”

It’s debatable whether the government has stabilized our coasts for environmental preservation or for more coastal development, as evidenced by the controversy around the national flood insurance program.

Meawhile, J. David Breemer of the Pacific Legal Foundation focuses on the issues of coastal erosion and private property rights:

As erosion squeezes public beach areas between the water and developed uplands, local governments from Texas to North Carolina have sought to create public areas out of privately owned beaches, to give the public a wider strip of shore. These governments contend that the public gains access to private beachfront land for recreational use, without any due compensation to the owner, whenever erosion strips away the natural vegetation so that land becomes a dry sandy area.

Breemer argues that governments should not be able to impose on landowners’ property rights even if for the public good. It seems to me that without some form of government intervention in land rights, we could see a return to beach segregation, as well as more coastal degradation. Of course, in some states, government intervention can be just as degrading. While North Carolina might be seeking public rights to private beaches, the state’s lawmakers’ heads are in the sand when it comes to climate change. In 2012, they voted to ignore rising sea levels from global warming for economic development planning purposes.

Overall, there was too little discussion of climate change in this debate. Climate change should be a priority in any discussion about our coasts as they are the most vulnerable parts of the nation. Kahrl’s book was chiefly about racism in America’s beaches, but he still gave considerable attention to global warming. The whole issue of beachfront access is moot if climate change makes it so that there are no more beaches to access.

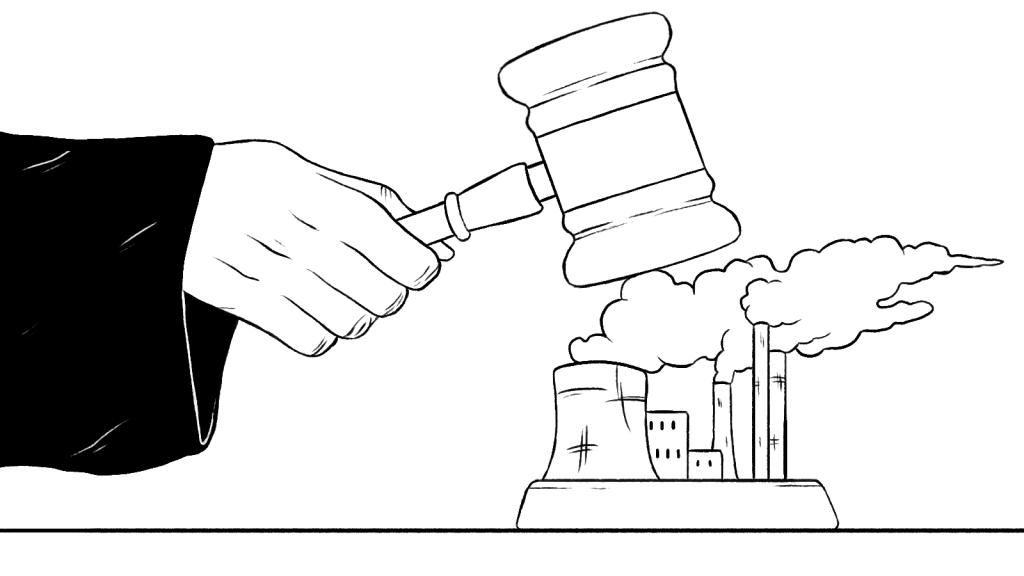

UPDATE: My fellow Grist Voice Heather Smith brought this L.A. Times column from Robin Abcarian to my attention. She reports that last Friday, California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) signed a law that allows the state’s Coastal Commission to fine people as much as $22,000 for trying to restrict public beach access through schemes like posting fake “no trespassing” signs near beach entrances. Before this, the commission had to file a lawsuit to make private beachfront landowners cease and desist. The sponsor of the new law, California Assembly Speaker Toni Atkins (D), had proposed an even stronger bill that would have given the commission the power to fine for other violations like unpermitted development or bad environmental mitigation.