The U.S. has quickly become a global fracking powerhouse, and it’s not slowing down.

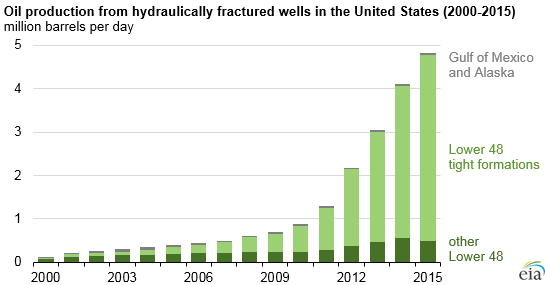

According to a March report from the Energy Information Administration, hydraulic fracturing now accounts for more than half of all U.S. oil output per day, compared with 2 percent in 2000. America’s 300,000 fracking wells pumped out 4.3 million barrels per day in 2015 — a staggering figure when compared to the 102,000 barrels a day in 2000. That growth has allowed the U.S. to “increase its oil production faster than at any time in its history,” the report notes, and places it third in the world for oil production, trailing only behind Saudi Arabia and Russia.

But fracking, a process that involves injecting a chemical cocktail into deep underground reserves of shale deposits to extract oil and gas — isn’t without its dark side. It risks water contamination and its methane leaks are poised to worsen climate change. And a growing body of scientific evidence has found that operations associated with fracking — specifically, the disposal of chemically laden wastewater into underground wells — can contribute to seismic activity.

The next person to occupy the Oval Office could decide whether this fracking boom will go bust. Or, at least, a Democratic president may try to stop it, as fracking emerges as a major concern in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination. Bernie Sanders has proposed to ban the process entirely through executive action, but his proposal could be as controversial as the drilling process itself: For instance, Mother Jones warned that if fracking were banned, consumers and operators would turn back to coal for energy — a fuel that releases less methane but is the world’s main climate change culprit. Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton has also struck a harder tone on fracking than she did as secretary of state, now claiming that as president she will enact limiting regulations on fracking operators that “by the time we get through all of my conditions, I do not think there will be many places in America where fracking will continue to take place.”

Either way, a ban on fracking won’t have the support of Congress. For the foreseeable future, fracking — and its side effects — will continue to be a powerhouse, and a problem.