In your pocket right now, you probably have some lanthanum, some europium, maybe a little cerium. At least, if you have your smartphone with you.

Called “rare earth” elements, these minerals critical to the operation of many modern devices live up to the scarcity implied by their name. Though the metals have been found in America, 97 percent of global supply comes from China. Two-thirds of that comes from an area in Inner Mongolia.

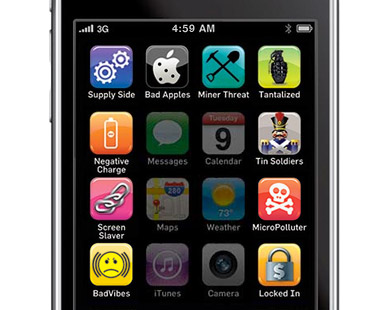

Where is the “do not ruin Inner Mongolia” app?

The Guardian details what the industry means for the surrounding region.

It was in 1958 — when [Li Guirong] was 10 — that a state-owned concern, the Baotou Iron and Steel company (Baogang), started producing rare-earth minerals. … “To begin with we didn’t notice the pollution it was causing. How could we have known?” As secretary general of the local branch of the Communist party, he is one of the few residents who dares to speak out.

Towards the end of the 1980s, Li explains, crops in nearby villages started to fail: “Plants grew badly. They would flower all right, but sometimes there was no fruit or they were small or smelt awful.” Ten years later the villagers had to accept that vegetables simply would not grow any longer. In the village of Xinguang Sancun – much as in all those near the Baotou factories — farmers let some fields run wild and stopped planting anything but wheat and corn.

A study by the municipal environmental protection agency showed that rare-earth minerals were the source of their problems. The minerals themselves caused pollution, but also the dozens of new factories that had sprung up around the processing facilities and a fossil-fuel power station feeding Baotou’s new industrial fabric. Residents of what was now known as the “rare-earth capital of the world” were inhaling solvent vapour, particularly sulphuric acid, as well as coal dust, clearly visible in the air between houses.

Discussion of the impacts of our technology (see: Foxconn) and of the impacts of extraction (see: everything on Grist.org, basically) needs to include the overlap between the two: the dirty, cheap processes by which the hardest-to-acquire components make their way to our hands.