Courtesy Nemo’s great uncle via FlickrTruth be told, I’m more interested in people who are overcoming barriers to progress than in the endless “does global warming exist?” debates. When your house is on fire, at some point you stop arguing with someone who says there’s no fire, and you focus on getting your family out. Or if the house is an inescapable planet, you get to work dousing the fire.

Courtesy Nemo’s great uncle via FlickrTruth be told, I’m more interested in people who are overcoming barriers to progress than in the endless “does global warming exist?” debates. When your house is on fire, at some point you stop arguing with someone who says there’s no fire, and you focus on getting your family out. Or if the house is an inescapable planet, you get to work dousing the fire.

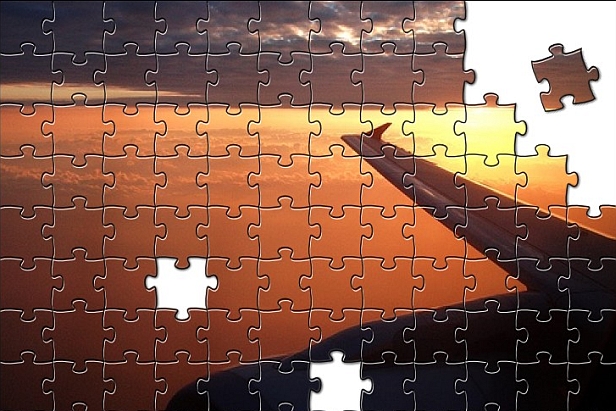

But … there’s this awesome metaphor in The Economist that’s useful for understanding how climate realists and skeptics talk past each other. It goes like this: If you view climate science as a jigsaw puzzle, the full picture becomes clear once you’ve got most pieces in place. A loose piece here and there doesn’t obscure the whole picture. If it’s a kitten in a laundry basket you’re looking at, you can be sure it’s a kitten in a laundry basket with only 90 percent of the pieces in place.

Courtesy peterjroberts via FlickrOn the other hand, if you view climate science as a house of cards, with each piece dependent on another piece, one loose card can topple the whole apparatus. (The chain is only as strong as its weakest link, to add yet another metaphor.) So the improper emails at the heart of the “climategate” uproar or one incorrect report on Himalayan glaciers can seem like a fatal blow, even though the body of scientific work confirming climate change vastly outweighs them.

Courtesy peterjroberts via FlickrOn the other hand, if you view climate science as a house of cards, with each piece dependent on another piece, one loose card can topple the whole apparatus. (The chain is only as strong as its weakest link, to add yet another metaphor.) So the improper emails at the heart of the “climategate” uproar or one incorrect report on Himalayan glaciers can seem like a fatal blow, even though the body of scientific work confirming climate change vastly outweighs them.

I find this illuminating. Understanding the difference between jigsaw people and house-of-cards people doesn’t resolve their disagreements. But it’s useful to see how they’re working off different metaphors. And The Economist’s thorough overview of climate science makes a strong case for why the jigsaw metaphor is the more appropriate one.

Bonus point: One reason why some people adopt the house-of-cards view is that they transfer the metaphor from fundamentalist religion. Fundamentalism requires that every single tenet of a holy scripture be true. If not, the whole apparatus topples. Hence the Biblical inerrancy view—the Bible is true not just as a whole, but in every single historical and scientific detail.

Most Christians I know don’t have this literalist view of the Bible. And I’ll leave it to theologians to explain whether this view of scripture makes sense. But if your faith rides on such a belief, you’re likely to look at climate change in the same way.

Hat tip to Clark Williams-Derry for spotting this.