Why can’t a revolution based on traditional Appalachian foodways be televised?Photo: April McGreger

Why can’t a revolution based on traditional Appalachian foodways be televised?Photo: April McGreger

Having watched the first three episodes, I’ve been thinking a lot about Jamie Oliver’s “Food Revolution” TV Show. Who can argue with his efforts to get fresh food into West Virginia’s schools? No doubt, the pantries and fridges in most school cafeterias need to be purged and restocked.

However, from what I can tell so far, our imported food revolutionary could stand to slow down and think a little bit harder about what he’s up to.

First, Oliver has demonstrated little knowledge of (or interest in) the traditional food culture of the region whose people he has set out to “save.” Over the decades, Southern Appalachians have been plagued by many well meaning do-gooders who wanted to teach those poor, underprivileged folks how to act more civilized–and eat better. Problem is, time and again, those reformers proved to be wrong.

According to the scholar and Appalachian native Elizabeth Engelhardt, for example, public health officials in the early 20th century targeted cornbread as the latest source of diet-based diseases in the South. Activists set out to create a social revolution in Appalachia by switching mountain women from cornbread to beaten biscuits, the symbol of aristocratic Southern cooking, for which their efforts were sardonically christened the “Beaten Biscuit Crusade.”

These biscuits required prohibitively expensive wheat flour, elaborate middle-class equipment– including a marble slab and modern ovens– and much more labor and time than their common cornbread. Beaten biscuits became an aspirational dish, separating the privileged from the poor and—following now discredited public-heath logic–the healthy from the unhealthy.

On the contrary, replacing whole-grain, freshly milled cornmeal with chemically bleached, nutrient-stripped, shelf-stable industrial flour proved nothing but detrimental to Appalachian health. You need only watch Appalshop’s 1977 documentary Waterground, about fifth-generation miller Walter Winebarger, to know that traditional wisdom foresaw this sad outcome.

Cornbread is just one of a long list of other traditional foods that were replaced with inferior industrial ones–many of which succeeded through propaganda campaigns. Lard from pastured hogs was demonized (largely by nutritionists funded by the vegetable oil industry) and replaced by now-maligned partially hydrogenated vegetable shortening, touted for its “purity.” Fresh-churned butter gave way to another trans-fat bomb, margarine. Much-beloved, live-cultured, and naturally low-fat buttermilk was banished in favor of inert, homogenized, pasteurized, growth hormone-injected, high-fat milk. Wholesome beans, greens, and cornbread gave way to sad casseroles based on canned soup and highly processed “cheese food.”

Overall, I worry that Oliver’s “Food Revolution” show obscures the fact that our food crisis is a symptom of underlying structural problems. In Appalachia, the government watched idly while the coal industry grabbed control of the region’s abundant natural resources. Widespread erosion of topsoil, contamination of drinking water, devastation of forests, and gut-wrenching destruction of the world’s oldest mountain range has resulted. The area remains in dire need of environmental protection. Is it any wonder why its economy is in ruins and the people in Huntington, West Virginia, are the unhealthiest in the country, as Oliver repeatedly reminds us?

Then there’s the workers’ rights crisis. Since stagnant wages compelled many women to leave the household and go to work a generation ago, who is supposed to make the from-scratch meals Oliver talks about? Many working mothers are on the clock until 5 or 6 o’clock. Add to that a long commute that many families endure to find jobs, and there is just no way. The system is unsustainable. Long hours at sedentary jobs with fast-food lunches produce unhealthy parents who then produce unhealthy children.

Moreover, the outrageous school district nutrition guidelines that Oliver struggles with are just one of a whole host of government policies that prop up the industrial food system that supplies most school cafeterias.

Our food system’s problems run deep–and the solutions won’t come easy. However, we can begin by recognizing, celebrating, and supporting wholesome, traditional foodways. They hang on despite being ground down by industrialization. Here, we find much-needed common ground between two often opposed groups–the liberal outsider and the mountain old-timer. This partnership could provide the fire for a real, lasting food revolution–one that heals Appalachian people, Appalachian economies, and Appalachian environments.

In that spirit, here are a couple of recipes meant to fuel a food revolution while celebrating mountain food culture, clean and healthy environments, and glorious spring!

(Next page: Recipe for Spring Vegetable Cornbread ).

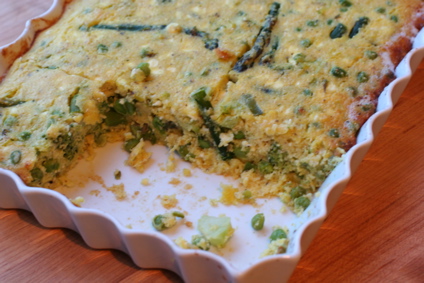

That good home cooking.Photo: April McGregerSpring Vegetable Cornbread

That good home cooking.Photo: April McGregerSpring Vegetable Cornbread

This recipe is my effort to reinvent a family favorite recipe for broccoli cornbread. Broccoli cornbread might sound healthy, but it’s not. The original recipe calls for a very sweet cornbread mix heavy on preservatives and trans fats, and light on nutrition. It also calls for a full two sticks of butter, or–worse–margarine. In my version, I’ve slashed the amount of butter, tripled the amount of vegetables, and relied on traditional, stone-ground ,organic cornmeal instead of a commercial mix. This recipe is still a cinch to pull together and the resulting dish exceptionally moist and chocked full of naturally sweet vegetables that kids love.

It takes less than 10 minutes to prep and 20 minutes to cook. I know that finding lots of fresh vegetables in rural areas can be difficult, so I’ve even tried this with a variety of frozen vegetables. It works great, and frozen are definitely the better nutritional alternative to canned (unless they are home canned). This recipe is also endlessly adaptable–try a summer vegetable cornbread bake with fresh corn, green beans, peppers, and tomatoes. It works just as well as a side dish as it does a main course.

5 cups mixed spring vegetables, cut into bite size pieces (frozen vegetables are fine and you can even use the microwave to steam them .if it’s more convenient). I used asparagus, leeks, snap peas, and broccoli in about equal amounts.

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon pepper

2 cups stone ground organic cornmeal

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

1 1/2 teaspoons baking powder

4 eggs

1 Tablespoon honey

2 cups cottage cheese (I used 2%)

6 Tablespoons unsalted butter (you can substitute olive oil if you prefer)

Preheat oven 400 degrees F.

Cut fresh vegetables into bite size pieces and steam until just tender. Frozen vegetables can simply be defrosted. Sprinkle with ½ teaspoon salt and ½ teaspoon black pepper and set aside.

In a 9-by-13 inch baking dish, place the 6 Tablespoons butter and place in the oven to melt.

In a mixing bowl whisk together cornmeal, 1 ½ teaspoons salt, and 1 ½ teaspoons baking powder

To the cornmeal mixture whisk in four eggs, cottage cheese, and 1 tablespoon honey. Fold in the steamed vegetables.

Remove the baking dish of melted butter from the oven. Pour about ½ of the butter into the cornbread batter and whisk to combine. Then pour the batter into the baking dish with the rest of the melted butter and use a spatula to spread the batter evenly.

Bake at 400 degrees F for 20 minutes or until a toothpick inserted into the center of the dish comes out clean.

Next page: Appalachian-style Wilted Salad

Appalachian-style Wilted Salad

This salad is very similar to the classic French salad of frisee aux lardons with a poached egg. However, this version is straight out of Appalachia. Traditionally the salad would include foraged spring greens, like dandelions and lamb’s quarters, as well as wild ramps. It’s just what the body needs to awaken it from winter’s slumber.

Makes 4 side salad servings

1/2 pound young spring lettuces

1 spring onion or ramp, sliced thinly

2 slices thick cut or slab bacon, cut into 1-inch pieces

3 tablespoons apple-cider vinegar

1 tablespoon honey

1 hard-boiled egg, chopped

Salt and ground black pepper

Wash lettuce and spin is a salad spinner until very dry. Place in a serving bowl with the spring onions.

Cook bacon in over medium heat until crisp. Transfer with a slotted spoon and to drain on paper towels. Hold bacon drippings warm in the pan over low heat.

Stir the vinegar and honey into the bacon drippings. Increase the heat to medium and cook the mixture until it is just bubbles.

Pour the hot dressing immediately over the lettuce and onions, tossing to coat and wilt the greens just slightly. Season with salt and pepper, top with chopped boiled egg, and serve immediately.