In June 1983, Newark’s close knit Ironbound community was overrun by investigators in Hazmat suits after EPA officials found dioxin at the Diamond Alkali chemical plant site.Photo: wirednewyork.comOn the morning of June 2, 1983, the governor of New Jersey declared a state of emergency. Speaking at a press conference in his Trenton office, then Governor Thomas Kean told reporters that the state’s Department of Environmental Protection had detected disturbingly high levels of dioxin at the former Diamond Alkali chemical plant at 80 Lister Avenue in Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood. With a three-page executive order, he shut down the Newark Farmer’s Market, a major food distribution center about a block from the Diamond site; stopped all train traffic around 80 Lister Avenue; and expanded an already existing ban against eating fish or shellfish from the Passaic River. Governor Kean stopped short of evacuation, but he offered temporary housing in Newark’s YMCA to those residents who lived closest to the plant site, and advised everyone to stay indoors during the cleanup operation.

In June 1983, Newark’s close knit Ironbound community was overrun by investigators in Hazmat suits after EPA officials found dioxin at the Diamond Alkali chemical plant site.Photo: wirednewyork.comOn the morning of June 2, 1983, the governor of New Jersey declared a state of emergency. Speaking at a press conference in his Trenton office, then Governor Thomas Kean told reporters that the state’s Department of Environmental Protection had detected disturbingly high levels of dioxin at the former Diamond Alkali chemical plant at 80 Lister Avenue in Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood. With a three-page executive order, he shut down the Newark Farmer’s Market, a major food distribution center about a block from the Diamond site; stopped all train traffic around 80 Lister Avenue; and expanded an already existing ban against eating fish or shellfish from the Passaic River. Governor Kean stopped short of evacuation, but he offered temporary housing in Newark’s YMCA to those residents who lived closest to the plant site, and advised everyone to stay indoors during the cleanup operation.

The next morning, June 3, a dozen or so federal Environmental Protection Agency investigators, dressed in Hazmat gear, fanned out across the Ironbound. They searched the Diamond Alkali plant site, the adjacent banks of the Passaic River and the surrounding streets, homes, schools, and businesses for any signs of stray dioxin. Press photos from the next few days show white-suited EPA workers literally vacuuming the streets of the Ironbound.

“It was like an invasion,” recalls Nancy Zak, a longtime neighborhood resident, who works for the Ironbound Community Corporation, a local nonprofit. “All these guys in these moon suits were walking around. We’re wearing our regular clothes. Nobody’s telling us we should dress or do anything differently. It was a shocking day for people.”

In the weeks following Governor Kean’s announcement, the men in the moon suits went house by house, street by street, factory by factory in the vicinity of 80 Lister Avenue. They collected dirt and weeds and street grit and the dust from vacuum cleaner bags and industrial air filters — 532 samples in total — and analyzed it all for the presence of dioxin. When the EPA released the final results of its cleanup operation, investigators reported “massive” amounts of dioxin on Diamond’s 80 Lister Avenue property, including a 51,000 ppb reading in the ground beneath an old storage tank. EPA workers also recorded high levels of dioxin off-site — in an air duct at the abandoned waste treatment facility next door to the Diamond plant, and in dust from the vacuum cleaner bag of Carol De Francis, who lived nearby at 13 Esther Street. In total, the off-site samples contained levels of dioxin ranging from zero to 15 parts per billion. At the time, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control considered concentrations above one ppb to present “an unacceptable risk to human health.”

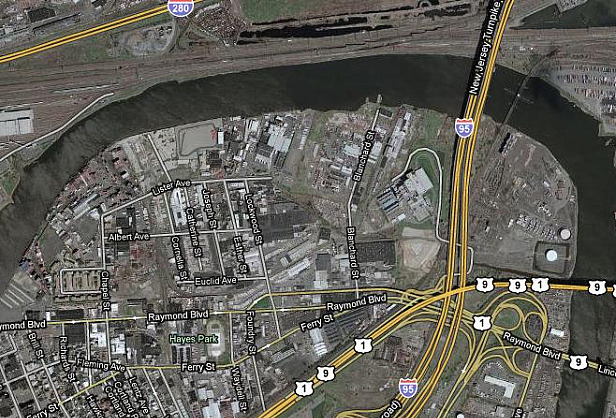

As it approaches Newark, the Passaic River loops sharply north and then just as sharply south again, as if the river is recoiling from the city. The Passaic’s S-shaped course around Newark creates a unique polyp of Ironbound land that is bordered on three sides by water. Diamond Alkali’s plant at 80 Lister Avenue sat at the very edge of the polyp, on 3.4 acres along the western bank of the Passaic. Diamond shared its bulbous peninsula with three other chemical manufacturing companies. To the east there was Sergeant Chemical, which Diamond eventually bought. To the south and west was the paint giant Sherwin-Williams. In the southwest corner was Duralac, Inc., a small producer of varnish, lacquers and enamel coatings. All the land occupied by these four chemical companies lies within the Passaic River flood zone. Sherwin-Williams is the only one of the four still operating, albeit in a different locale. Benjamin Moore Paints occupies the old Sherwin-Williams space now.

The Passaic River loops around the Ironbound. Diamond Alkali had riverfront property.

The Passaic River loops around the Ironbound. Diamond Alkali had riverfront property.

This swath of Ironbound is a knot of homes and heavy industry. The factories, arrayed along Lister Avenue, command the riverfront. Behind them, modest homes line the streets. Industrial manufacturing — mostly of farm chemicals — has been going on at 80 Lister Avenue since Alfred and Edwin Lister bought the property in 1850. The brothers built the Lister Agricultural Chemical Works factory where they ground cattle bones into fertilizer. Kolker Chemical Works acquired the Lister Avenue property in the early 1940s. Kolker made farm chemicals too. But the pesticides and herbicides it produced on the site were not so benign.

Kolker manufactured DDT and the phenoxy herbicides 2,4,5-T (2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid) and 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid). DDT is a pesticide that killed insects by attacking their nervous systems. Diamond stopped making DDT in the late 1950s, more than 20 years before the EPA banned its use. From the late 1950s until 1969, when Diamond closed the Lister Avenue plant, phenoxy herbicides were the only products manufactured there. Phenoxy herbicides were the ingredients in Agent Orange.

In August 1983, two dioxin-related lawsuits were filed on behalf of the Ironbound community: one against Diamond and one against the state’s Department of Environmental Protection, as a way to compel the agency to modernize and organize so that it could properly direct Diamond’s cleanup efforts. Diamond was sued for damages, and for a peek into the company’s files. This was one of the earliest hazardous waste cases in New Jersey and it was difficult to get information at the time.

A group of Viet Nam veterans frustrated by government inaction also filed suit against Diamond Alkali, Dow Chemical, Monsanto, and other manufacturers of Agent Orange. The plaintiffs — more than two million veterans — were after compensation for health problems they blamed on wartime exposure to Agent Orange. Their 1982 class action lawsuit forced Diamond and its co-defendants to hand over reports, memos, letters, invoices, manufacturing diagrams, every scrap of paperwork that might shed light on the claims.

The discovery process and the decontamination of the Ironbound proceeded in tandem over the next few years. While teams of private contractors dismantled and sealed the Diamond plant site, and Ironbound activists agitated for more and better public health studies, attorney Michael Gordon spent his days sifting through box after box of yellowed paperwork. He was looking for a memo or a letter or a report, some written evidence that Diamond had been aware of its dioxin problem and yet had done nothing to address it.

It was a tedious job. But one afternoon in 1986, Gordon found the smoking gun: a file of correspondence — and related internal memos — between a Diamond employee and officials at the C.H. Boehringer Sohn chemical company in Germany. The exchanges left no doubt that Diamond managers knew dioxin was contaminating their manufacturing process; that they knew dioxin was the cause of the chloroacne outbreak among workers at the Newark plant; that they knew how to eliminate the dioxin from the process; and that they knew all of this as early as 1957. “I went back and read [the file] a few times,” says Gordon. “And I remember saying, okay, that’s it. I’m done.”

Although dioxin was first synthesized in a German laboratory in 1872, it really is a 20th Century phenomenon, a nasty little legacy from the age of chlorine. As early as the 1920s, organic chemists began stitching chlorine atoms to hydrocarbon molecules. In so doing, they created whole new classes of chemicals, from durable oily substances like PCBs to powerful herbicides like DDT to unintended poisons like dioxin. The most dangerous dioxin, TCDD, was the one being generated in massive quantities by workers at 80 Lister Avenue.

Temperature, as it turned out, was the key to preventing TCDD from contaminating the Agent Orange batches. Above 320 degrees F, trichlorophenol, one of the two phenoxy herbicides used to make Agent Orange, becomes unstable. The chemical bonds that hold its chlorine and carbon and oxygen atoms together come undone. As the compound unravels, new molecular matchups lead to new compounds. One of the new compounds is TCDD. The hotter the reaction, the more TCDD is produced.

The remains of the old Diamond Alkali factory were sealed inside 932 shipping containers and buried beneath this six-acre concrete mound at 80 Lister Avenue.Photo: Mary BrunoIn 1967, a decade after it was first warned about dioxin, Diamond finally took some action, upgrading the ventilation system in its Lister Avenue factory. By then the company was one of the largest Agent Orange manufacturers in the U.S. The Newark plant turned out 16 million pounds of trichlorophenol between 1952 and 1968. Diamond workers turned out the last batch in June of 1969. Two years later, in March 1971, Diamond sold the property to Chemicaland, a corporation that made benzyl alcohol, a multipurpose organic solvent used by ink, paint, and lacquer manufacturers.

The remains of the old Diamond Alkali factory were sealed inside 932 shipping containers and buried beneath this six-acre concrete mound at 80 Lister Avenue.Photo: Mary BrunoIn 1967, a decade after it was first warned about dioxin, Diamond finally took some action, upgrading the ventilation system in its Lister Avenue factory. By then the company was one of the largest Agent Orange manufacturers in the U.S. The Newark plant turned out 16 million pounds of trichlorophenol between 1952 and 1968. Diamond workers turned out the last batch in June of 1969. Two years later, in March 1971, Diamond sold the property to Chemicaland, a corporation that made benzyl alcohol, a multipurpose organic solvent used by ink, paint, and lacquer manufacturers.

It took awhile, 14 years to be exact, but dioxin came back to haunt Diamond. In the deluge of documents, depositions and media stories unleashed by all the litigation, the truth about operations at Diamond Alkali came tumbling out. It became painfully clear that the only thing more careless than the chemistry at 80 Lister Avenue was the housekeeping.

In testimony, Diamond plant worker Chester Myko called the floor in the trichlorophenol building the “dirtiest place in the entire plant.” The amount of Agent Orange batter that was regularly slopped onto the plant floor made the surface so slick that walking across it was treacherous. Workers hosed down the floor with sulfuric acid every week or so, directing the wastewater into open trenches, which took it outside the building and into the Passaic.

Aldo Andreini cleaned the 10,000-gallon tanks that were used to store the Agent Orange ingredients. Once or twice a month, Andreini shoveled sediment from the storage tanks into metal drums. The liquid and solid waste that got spilled onto the ground during the transfer would be washed away — into the Passaic.

Harry Heist was employed at Diamond from 1966 to 1969. “There were spills all the time,” Heist told The Newark Star-Ledger in June 1983. “The reactors would run away, boil over and stuff would flow down the sides of the tanks and troughs on the floor that led to the river. The stuff was all over the place.” Diamond’s waste disposal strategy, in the words of its workers, amounted to “dumping everything” into the Passaic River.

As Michael Gordon prepared the Ironbound case for trial, the Marisol Corporation, hired by Diamond and supervised by the state, took the 80 Lister Avenue plant apart. Marisol workers broke down and gathered up all the equipment that was used to make Agent Orange. They packed up every square inch of flooring and wall board, every pipe and valve, every beam, brick, gate, fencepost, lock, chain, window, door, shelf, closet, light fixture, sink, toilet, desk, filing cabinet, phone, wastepaper basket, clipboard, pencil — everything. They laid the bits and pieces of Diamond Alkali to rest, without ceremony, right there at 80 Lister Avenue in the six-acre, clay-sealed, membrane-capped, gravel-topped grave with the white planters on top. Federal EPA officials proposed cremating Diamond Alkali on site. Ironbound residents soundly rejected the EPA’s “on-site incineration” plan as unsafe. Instead, the remains of Diamond Alkali were sealed inside 932 shipping containers along with the neighborhood’s toxic dirt and the dust from Carol De Francis’s vacuum cleaner bag.

The plant managers and executives at Diamond Alkali couldn’t have known about dioxin’s destructive effect at the cellular or molecular level. They did know what was causing their chloroacne problem though, and they had been warned about the potential for far more serious health consequences. Chemical companies in the U.S. and Europe were freely, if quietly, exchanging information and concerns about dioxin. “Tragically,” writes toxicologist Ellen K. Silbergeld in the 1993 book Toxic Circles, “while industry shared this information within its own circle, industry medical and toxicological staff withheld such knowledge from those most at risk, the workers.” No dermatologist or plant manager ever told the crews at 80 Lister Avenue about the true nature of the chemicals they were handling every day.

The Ironbound community’s case against Diamond Alkali — by then the Diamond Shamrock Corporation — was settled, out of court, on Thursday, Jan. 24, 1991. Diamond agreed to pay plaintiffs $1 million in damages, but refused to admit any liability. The settlement came rather abruptly about seven weeks into the trial. Diamond had yet to present any of its expert witnesses. Diamond’s settlement offer was far less than the millions in damages being sought.

When I ask Michael Gordon whether he was satisfied with the outcome of the case, he offers a qualified yes. “Given where the Ironbound Community was and the resources it had, and the point in time in the development of these kinds of cases, it was an excellent result. We got a few million and made sure there was a proper recognition of the extent of the problem.” In big picture terms, says Gordon, the dioxin case was a wake up call for New Jersey’s environmental regulators. In its aftermath, the state’s standards for hazardous waste regulation and litigation became far more rigorous and sophisticated.

Twenty-seven years after Governor Kean’s emergency 1983 press conference, the dioxin that Diamond Alkali dumped into the river is still there. The New Jersey Supreme Court took pains to mention this sad fact in its 1992 opinion from the Diamond vs. Aetna case. The Honorable David S. Baime, writing for the majority said: “We digress to note that neither Federal nor State environmental protection agencies have directed Diamond to remediate the damage to the river. As Diamond correctly points out in its brief, the claims which are the subject of this litigation do not encompass losses resulting from the discharge of substances into the Passaic River. We nevertheless recount this evidence because it bears upon the state of Diamond’s knowledge and intent regarding the environmental damage caused by its operations. At least to some extent, this evidence disclosed a less than benign indifference to the consequences of Diamond’s operations that directly bears upon whether other discharges and their effects were accidental or inadvertent.”

The talk nowadays, and there is lots of it, involves whether and how to safely dredge the dioxin-drenched sediments, and even more controversial, who should pay for it. Michael Gordon is helping the state sort through the complex legal issues.

We paddle into Newark with the dusk — Carl, my kayaking buddy, and I — around a bend in the river and past a decommissioned Bascule bridge frozen in the open position with a welcome message spray-painted on its underside: Newark Sucks.

Coming into Newark, just upstream from the Diamond superfund site where dioxin remains buried in the river sediments.Photo: Mary Bruno

Coming into Newark, just upstream from the Diamond superfund site where dioxin remains buried in the river sediments.Photo: Mary Bruno

The river is narrow on the approach, almost a culvert, corseted by bulkheads on both banks and domed by closely packed rusting iron bridges. The modest skyscrapers of downtown rise up from the western shore. The water before us is dead calm, an obsidian mirror as shiny and impenetrable as the windows of a stretch limousine. It is Sunday evening. In a few minutes streetlights will begin to flicker on, but for now the city is hushed and shrouded in twilight.

I slow down as I approach the rusting New Jersey Transit Bridge, and start to back paddle when I notice a train pulling out of Penn Station. I don’t want to be under the bridge when the train crosses it. I lay my paddle across the cockpit and cover my ears against the squeal and rattle of the train wheels on the steel tracks above.

Ten feet below me, buried in the dark pudding of silt and muck at the bottom of the river, is the world’s second largest deposit of dioxin. There are other poisons down there too: PCBs, and DDT, and the whole cast of heavy metals. All the toxic byproducts of Newark’s electroplating, hat-, paint-, varnish-, leather-, fertilizer-, and pesticide-producing past are there below me, bound up in the Passaic River mud. Dioxin is the most deadly of them all, man’s most carcinogenic creation. I draw my paddle up out of the water and slide the small rubber drip guards as close to the paddle blades as they’ll go. I don’t want any of this water dribbling down the paddle shaft and dripping on to me.

This is the second installment of a two-part excerpt from This American River: From Paradise to Superfund, Afloat on New Jersey’s Passaic.

Check out Part One here.