A meter in the kitchen of the “Smart Energy Experience” home tracks the amount of electricity being consumed and its cost.Photo: Southern California EdisonThis is the second in a two-part series. You can find yesterday’s installment here.

A meter in the kitchen of the “Smart Energy Experience” home tracks the amount of electricity being consumed and its cost.Photo: Southern California EdisonThis is the second in a two-part series. You can find yesterday’s installment here.

When experts try to describe the smart grid, their favorite analogy is the internet.

Just as the internet enabled interactive, two-way communication, the smart grid, we’re told, will deploy sensors and software to digitize a century-old analog electricity distribution system, transforming it into one capable of integrating renewable energy and decentralizing power production.

But while the benefits of the internet are manifest — YouTube, Facebook, Grist! — what will the smart grid do for you and me?

For most people, the most familiar part of the smart grid is the smart meter, those wireless digital devices being installed in homes by the millions so that residents can monitor electricity use in real time rather than through a monthly utility bill that arrives long after the power has been consumed.

Smart meters have been controversial in Northern California, where a number of communities have moved to ban the devices over fears about the potential health effects from their emission of electromagnetic frequencies. (Mobile phones, televisions, and other electronic devices also emit electromagnetic frequencies, and so far there has been no scientific evidence to support the health claims about smart meters.)

A sunnier view of the smart meter as a gateway to a new energy future emerges in Los Angeles, where utility Southern California Edison has built a model home with smart grid technology embedded in everything from the dishwasher to the thermostat.

“It’s much easier to show than tell,” says Mindy McDonald, a Southern California Edison project manager. She is standing outside the “Smart Energy Experience” home that’s been constructed inside the utility’s Customer Technology Application Center, just off the 210 freeway in the inland suburb of Irwindale. “Grappling with the smart grid, it’s much easier to just walk people through,” says McDonald.

The idea is to show people how smart grid technology can cut their electricity bills, reduce the need to build additional fossil fuel plants, and therefore cut greenhouse gas emissions.

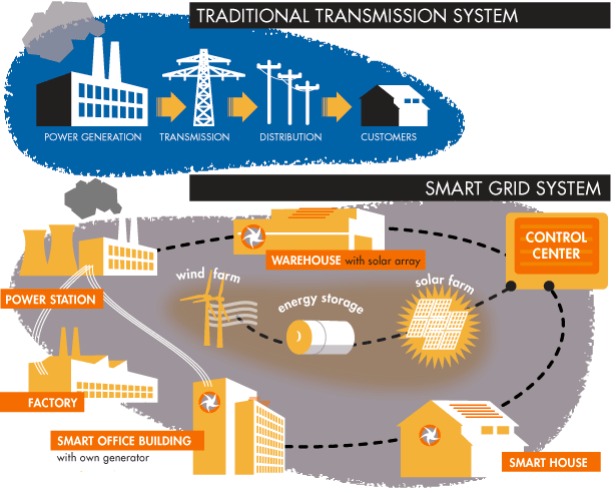

The smart grid links every element of the power system, from large generators to homes and offices. The control center sends out price and control signals throughout the system and keeps it balanced.Image: Dillon Thompson Design

The smart grid links every element of the power system, from large generators to homes and offices. The control center sends out price and control signals throughout the system and keeps it balanced.Image: Dillon Thompson Design

A Coda electric car is parked in the stylish suburban ranch’s garage. Solar panels, a solar hot water system, and a wind turbine sit on the roof. LEDs provide the home’s lighting, and every appliance contains communication chips, allowing them to “talk” to each other and to the utility through the smart meter attached to the front of the house.

A video screen in the living room displays the home’s energy management system, and a large flat screen in the kitchen tracks the amount of electricity being consumed and its cost.

When McDonald turns on the washing machine and the air conditioner and then plugs in the car, an “energy speedometer” on the screen shows the cost of electricity rapidly accelerating from 11 cents an hour to $2.81. The display also tells the homeowner how much electricity has been consumed so far in the day and the price per kilowatt-hour.

“It’s really has an impact when you can see how much it’s costing and they realize that maybe they should turn something off,” McDonald says. “Most people don’t pay any attention to what electricity costs until they get their bill and it’s too late to do anything about it.”

The utility so far has installed smart meters in about a fifth of the 4.9 million households and businesses it serves. Beginning in January, those customers can set a monthly electricity budget and receive a text alert, email, or phone call when they’re on track to exceed their limit, according to McDonald.

Another upcoming program, called Save Power Days, will let customers sign up to have their electricity consumption automatically curtailed when demand — and prices — spike, say on a hot summer afternoon. In return, they could save up to $200 a year on their bills.

“Your meter would receive a notification and send it to your programmable communicating thermostat, and it would automatically raise or lower the home’s temperature,” says McDonald. “If you have energy management system, you could set it up any way you want.”

She touches the iPad that controls the house to show how a smart house would react. When the meter signals the energy management system, it adjusts the thermostats, turns off the air conditioner, and switches on ceiling fans. Window blinds lower to block sunlight and keep the house cooler while the lights are dimmed.

“It’s all automatic,” notes McDonald. “If you are home and you don’t want to participate, you can opt out by turning up thermostat temperature, or just push ‘opt out’ on the screen.”

The Smart Energy Experience home.Photo: Southern California EdisonTheodore F. Craver, Jr., chief executive of Edison International, the utility’s parent company, said in an interview that these technologies will change people’s relationship with the energy system.

The Smart Energy Experience home.Photo: Southern California EdisonTheodore F. Craver, Jr., chief executive of Edison International, the utility’s parent company, said in an interview that these technologies will change people’s relationship with the energy system.

“Most people think it’s out of sight, out of mind — as long as the light switch goes on and an appliance can be plugged in, that’s it,” he says. “Now the customer will interact with the grid instead of just being passive.”

The question is just how successful utilities will be at persuading people to become active participants in managing their energy consumption.

“Too many of them are saying just giving people more and better information about electricity use, for example, is automatically a huge environmental plus,” Ralph Cavanagh, the co-director of energy programs for the Natural Resources Defense Council, said at the E2 Environmental Entrepreneurs recent conference.

“I’m all for better information but the average electric bill in the average U.S. household is $3 a day,” he continued. “If all you’re talking about is giving people more and better information about their $3 a day, at some point many of them are going to conclude that they have more important things to do with their time.”

Said Jesse Berst, president of the Center for Smart Energy, a research and consulting firm in Redmond, Wash.: “I think it’s a lot easier to teach devices to be smart about energy than to teach people to be smart about energy. I don’t see people clustered around the warmth of the home energy management console.”

They might well start paying more attention when utilities begin introducing what is called “time of day” pricing. Since the smart grid lets utilities monitor electricity consumption in real time, they can start charging consumers higher prices when demand spikes and thus the cost of power rises.

In other words, if you set your air conditioner at arctic temperatures when all your neighbors are cranking up their units on a sweltering day, you’ll pay the price. The flip side is that your smart meter could tell your smart washing machine and dishwasher to delay switching on until power prices dr

op in the evening.

The smart grid offers Joe and Josephine Ratepayer other benefits as well. For instance, if a storm knocks out a power line, all the 1,500 homes on a typical Southern California Edison circuit served by that line will lose electricity. The utility usually doesn’t find out about such outages until customers call to complain. It can be hours before a repair crew can be dispatched and the problem located and fixed.

As part of its smart grid program, Southern California Edison will be installing sensors on the top of power poles to monitor the circuit. If a line goes down, sensors will reroute power to minimize the number of homes affected by a blackout. The sensors will also notify the utility of the problem and its location and the system will automatically dispatch a repair crew.

That means fewer people sitting in the dark.

Edison International’s Craver says that a grid with this kind of smarts could make a huge difference. “There’s such a high potential for change, and a perhaps pretty radical difference that will start to be created where the grid has a two-way communications capability, and some level of intelligence actually built into the system.”