Photo: Dr. Joe HummerWe have some ideas about how to make cars less destructive — but what about the streets they drive on? Is there a way to accommodate a growing population and its continued need to drive, without ending up in a scenario where we all live in the median of a 120-lane highway?

Photo: Dr. Joe HummerWe have some ideas about how to make cars less destructive — but what about the streets they drive on? Is there a way to accommodate a growing population and its continued need to drive, without ending up in a scenario where we all live in the median of a 120-lane highway?

Researchers at North Carolina State University have some ideas. In a recent study, they tested the efficiency of “superstreets” — which sound like giant highways, but are actually an alternative to making streets bigger. These streets’ U-turn-based intersections allow traffic to move more efficiently and with fewer accidents, without expanding the size of the road.

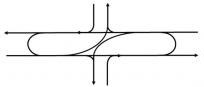

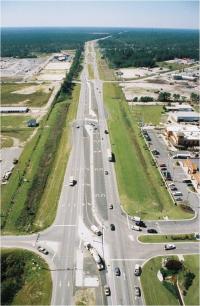

“Superstreets,” you say? Never heard of ’em. Superstreets are intersections between a major arterial road and a minor road that restrict or don’t allow direct left turns. To turn left from the minor road onto the major road, you first turn right, then make a U-turn across the median. Some superstreets allow direct left turns from the arterial road onto the minor road; others require U-turns for that too. There aren’t a lot of them at this point — a few in North Carolina; some in Maryland, Michigan, and Minnesota; one in Texas. Most are in rural areas. But the N.C. State researchers think they may represent a better solution for many streets in the U.S.

What’s so super about superstreets? It’s a way to avoid — or at least put off — expanding the road or intersection. For the same concrete footprint, you can get a road that provides quicker and safer travel — 20 percent shorter average travel times in the N.C. State study, and 63 percent fewer injury-causing accidents. The travel time savings were even bigger at times of high congestion.

Here’s how it works: It’s relatively easy to set up the signals on a one-way street to keep traffic flowing smoothly. You just set up the signal timing and speed limits so that when a cohort of cars reaches the light, it turns green. As you add more complexity — cross-streets, two-way traffic, left turn lanes — it gets harder to achieve what the researchers call “perfect signal progression.” Left turn lights in particular are lousy for this, since everyone has to wait while a few cars go, which bunches up not only motorists’ panties but also the flow of traffic. Because of the restrictions on how you can enter and leave the arterial, superstreets are more like two one-way streets running parallel than they are like a two-way road. That means it’s easier to use signals to control and improve the flow of cars.

It sounds confusing as hell to make a turn, though. Yeah probably. It’s hard enough just understanding the diagram. That was residents’ main objection to the existing superstreets that researchers studied — they found them confusing. Businesses weren’t crazy about them either, since confused motorists who aren’t quite sure how to turn left into your parking lot don’t bring in a lot of dollars. The researchers figure that people will get accustomed to superstreet operations as they become more commonplace.

What about pedestrians? It’s a little academic right now, since the existing superstreets are not in high-pedestrian areas. But in theory, superstreets are more pedestrian-friendly than conventional arterial roads, says Dr. Joe Hummer, who led the study. Because the signal progression is so easy to control, “there’s an ability to put mid-block pedestrian signals pretty much anywhere you want to on a superstreet without affecting the quality of flow on the main street for traffic,” Hummer says. “Anywhere they felt there was a demand for crossing, we could put a traffic signal.” Engineers usually fight against putting signals on a large road because they do a number on traffic flow, says Hummer, but on a superstreet that’s not the case.

It’s also easier to control the speed of traffic on a superstreet, to slow down cars in areas where you want to encourage pedestrian traffic. And pedestrians are less endangered because there are fewer directions in which traffic can move at each intersection. “The only way a pedestrian can get hit crossing a superstreet is if somebody runs a red signal,” Hummer says.

Coming to your neighborhood? Superstreets won’t be the right solution for every area. Because they’re so heavily U-turn-based, they need a certain amount of room, either a wide median or a curb cutout allowing for wider turns. But Hummer is optimistic about their possibilities outside of the large rural arterials where they’re currently used.

“We’re hurt a little by the name,” Hummer says — it makes people think of giant freeways. “But superstreets can be slow, and friendly.”