As the deadliest fires in California history swept through leafy neighborhoods here, Kathleen Sarmento fled her home in the dark, drove to an evacuation center, and began setting up a medical triage unit. Patients with burns and other severe injuries were dispatched to hospitals. She set about treating many people whose symptoms resulted from exposure to polluted air and heavy smoke.

“People were coming in with headaches. I had one. My eyes were burning,” said Sarmento, the director of nursing at Santa Rosa Community Health, which provides health care for those who cannot afford it. But respiratory problems — coughs and shortness of breath — were among the biggest risks. “We made sure everyone had a mask.”

More than half of the evacuees at the shelter that October night were elderly, some from nursing homes who needed oxygen 24/7. Sarmento scrambled to find regulators for oxygen tanks that were otherwise useless. It was a chaotic night — but what came to worry her most were the weeks and months ahead.

“It looked like it was snowing for days,” Sarmento said of the falling ash. “People really need to take the smoke seriously. You’ve got cars exploding, tires burning. There has to be some long-term effect” on people’s health.

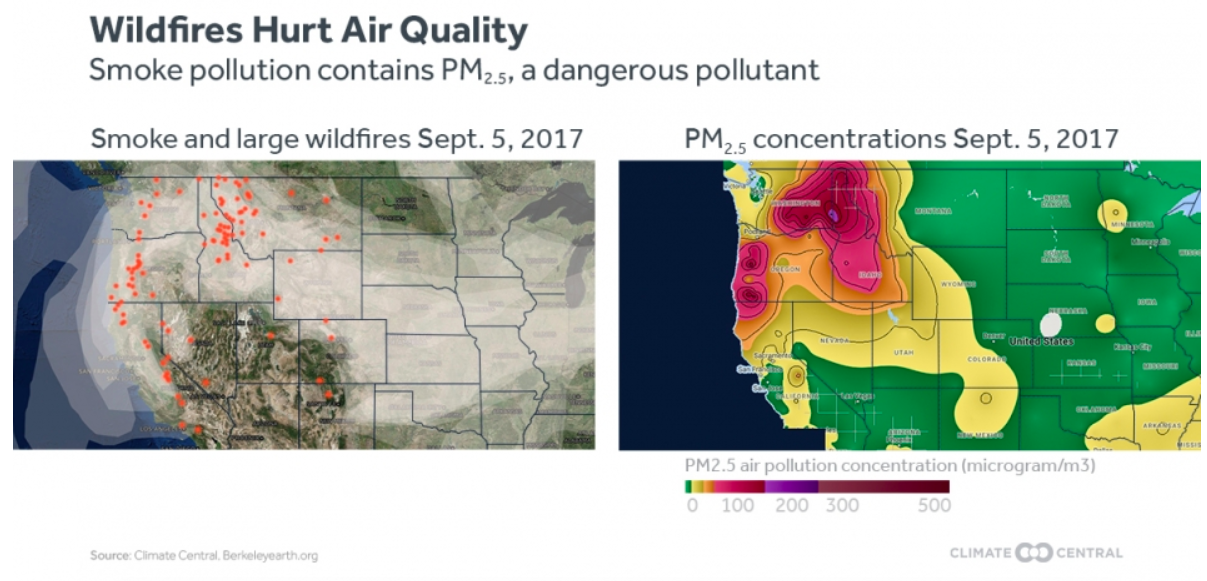

From Puget Sound to Disneyland and east over the Rockies, Americans have coughed and wheezed, rushed to emergency rooms, and shut themselves indoors this year as pollution from wildfires darkened skies and rained soot across the landscape. Even to healthy people, it can make breathing a miserable, chest-heaving experience. To the elderly, the young, and the frail, the pollution can be disabling or deadly.

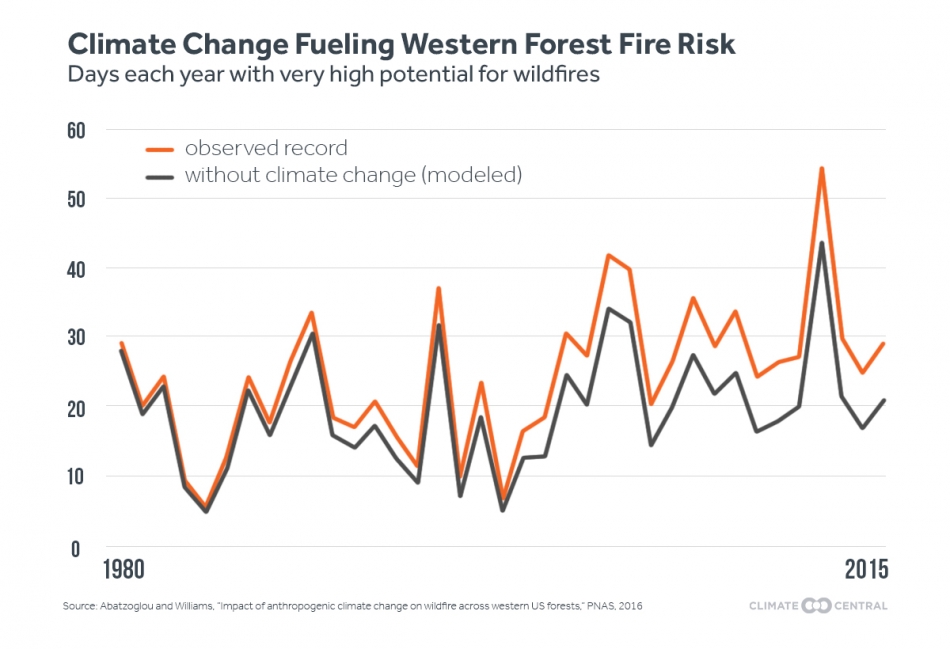

Even though the nation has greatly improved air quality over the last 40 years through environmental regulations and technological improvements, the increasing frequency of large wildfires now undermines that progress, releasing copious pollutants that spread far and wide through the air and linger long after the fires are extinguished.

Scientists say climate change, degraded ecosystems, and the fickleness of the weather have been amplifying fires in forests, grasslands, and neighborhoods throughout the West. Nine times more western forestland is burning in large fires each year on average now than 30 years ago, according to calculations by two leading scientists.

The blazes create smoke waves — pulses of pollution containing everything from charred plastic residue to soot to other small particles that lodge deep in the lungs. They can trigger short-term ailments, such as coughing; worsen chronic diseases, such as asthma; and lead to long-term damage, including cancer.

The effect of the fires in Northern California’s wine country, which destroyed thousands of homes and killed 43 people, went well beyond the burn zone. The smoke choked the San Francisco Bay Area, home to 7 million people in nine counties, for days.

Colette Hatch, 75, of Santa Rosa, who suffers from lung disease and uses a nebulizer daily, evacuated to her daughter’s home in Sunnyvale, in Silicon Valley, when the fires came. But even nearly 100 miles away, Hatch said she struggled to breathe, coughing so hard she couldn’t sleep.

Wafting beyond Oakland and Livermore in the East Bay, the smoke headed into California’s agricultural heartland, the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys.

Known collectively as the Central Valley, it stretches for hundreds of miles roughly north to south, bracketed by mountain ranges that trap some of the dirtiest air in America. Increasingly, wildfires like the ones in Northern California’s wine country funnel smoke into the chute, significantly raising the pollution levels in places as far away as Fresno.

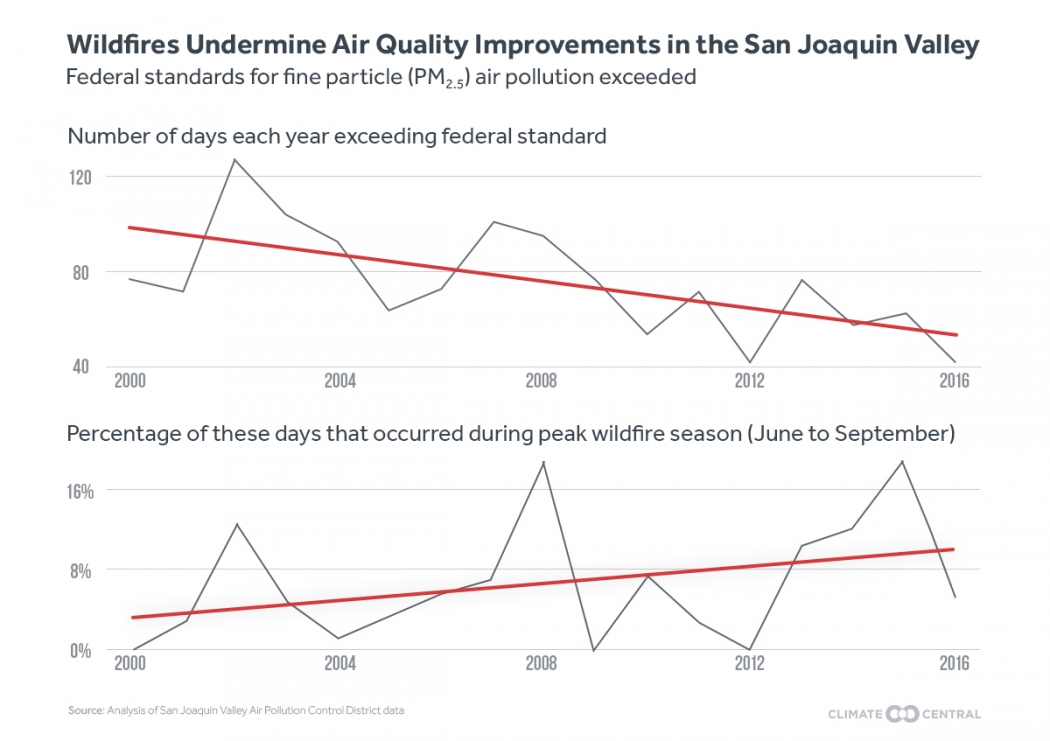

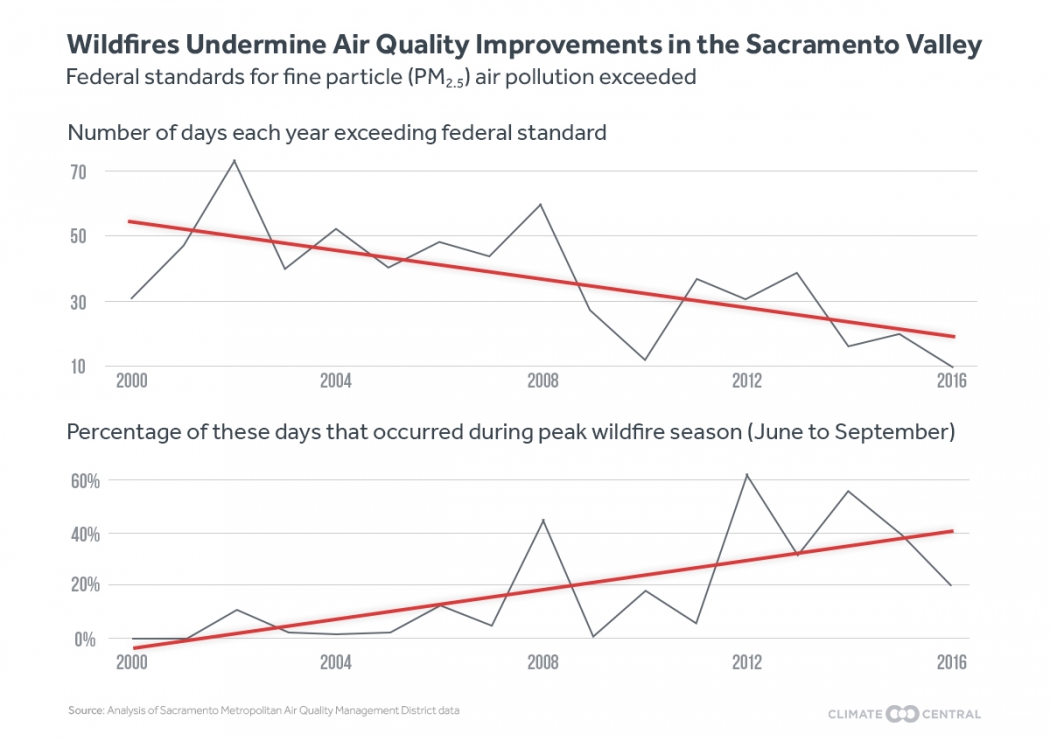

Climate Central, a research and journalism nonprofit, examined air district data from California’s Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys. The analysis showed that while the number of heavily polluted days is falling overall each year on average, those days are occurring more frequently during the peak fire season. The researchers say wildfire smoke is to blame.

Monitors in the San Joaquin Valley and San Francisco Bay Area showed levels spiked in October as the wine country fires sullied skies.

With large wildfires on the rise, smoke and the attendant breathing ailments seemed everywhere this year. In September, smoke from fires burning in California, the Pacific Northwest, and Montana pushed as far east as Pennsylvania. Smoke triggered emergency declarations in Washington state and California. The Evergreen State was experiencing a few fires of its own in July when it was hit by smoke waves that poured across the Canadian border. And smoke returned to much of the northwest in August and September as fires broke out in the Cascades and the Columbia Gorge.

“I remember waking up one morning and the sky was orangey-red and there was ash falling out of the sky,” said Jeremy Hess, a researcher and physician at the University of Washington in Seattle. “This summer was very busy for us in the emergency department and we were often over capacity. If it wasn’t the smoke, it was the heat,” Hess said.

As the world warms, environment and health suffer

The blazes came after record-breaking late summer heat dried out grass that had flourished following record-breaking winter rains — both forms of extreme weather that are worsened by global warming. In addition, a high pressure system over the Pacific fanned the flames by driving unusually hot and powerful seasonal winds into Northern California from the dry highlands of Nevada.

The immediate precipitant may have been sparks from power lines, although investigations into the causes are ongoing. But a changing climate helped fuel the blazes.

“Climate change was not the cause but it’s definitely an ingredient,” said Park Williams, a climate and ecology researcher at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. And that means worse is to come.

Williams said there was a clear connection between the nearly 2 degrees F overall increase in global temperature since the late 1800s and the severity of these and other fires. (Warming in the West has been outpacing the global average in recent decades because of natural cycles.)

“Fire really responds strongly to even that small of a change of temperature,” said Williams, whose assessment of global warming’s role in the wine country fires is shared by other experts.

Environmentally, the fires are a double whammy: They destroy trees that help to slow global warming by absorbing heat-trapping carbon dioxide as they grow. They also release carbon dioxide stored within, as well as black carbon that melts snow and ice.

Environmentally, the fires are a double whammy: They destroy trees that help to slow global warming by absorbing heat-trapping carbon dioxide as they grow. They also release carbon dioxide stored within, as well as black carbon that melts snow and ice.

Research indicated in 2015 that large fires had helped turn California’s forests and other lands into polluters, releasing more carbon to the atmosphere than they suck back in. The state’s wildlands released more heat-trapping pollution from 2001 through 2010 than Vermont’s entire economy. Rising temperatures aren’t the only cause — the forests are overloaded with fuel following more than a century of aggressive firefighting.

While public attention has tended to focus on other health risks from climate change such as heat stroke in summer and the spread of mosquito-borne diseases northward, the effects of smoke pollution have been gaining more attention following dramatic and widespread wildfires.

The most dangerous pollution from wildfires is fine soot — “really small particles that we know can get into the lungs,” said Colleen Reid, a geographer at the University of Colorado who researches climate change and human health. It’s known as PM2.5, meaning “particulate matter” that’s less than 2.5 microns wide, only visible using microscopes.

It can nestle into lung tissue and pass into the bloodstream, contributing to an array of health problems, including infections and, potentially, heart attacks.

Symptoms related to smoke waves may not be diagnosed right away, making it hard to recognize the role a fire may have played in an illness or death. Reid led an analysis published a year ago based on hundreds of studies into fire pollution’s health effects. The clearest links shown in the studies were between PM2.5 and asthma and other breathing problems; links to heart disease were less conclusive.

Researchers from leading American universities examined fire pollution across the West, finding that two of every three counties in the region suffered at least one smoke wave from 2004 through 2009. When they correlated those findings with medical data, they found a 7 percent jump in breathing-related hospitalizations after smoke levels were most extreme.

“An acute fire lasting, for example, days to weeks, may not show up as an immediate problem but as health problems that may occur over a time span of weeks or months,” said Loretta Mickley, a Harvard researcher who worked on the study.

This summer in California

Elva Hernandez, 51, has lived in the San Joaquin Valley most of her life. She’s suffered from asthma since she was 10. This summer she was stuck inside her house for several weeks as smoke waves suffocated her neighborhood in the small town of Kerman, California, near Fresno.

“The smell, all the dust, the smoke, the smog, everything, it’s just — you can’t breathe,” said Hernandez, a stay-at-home mom whose husband analyzes lab samples at a hospital. “You can’t live your life normally.”

The San Joaquin Valley is home to 4 million people, many of them poor. One in 6 children suffers from asthma. Poor people often are most affected by air pollution, partly because they tend to live in more drafty housing in more polluted neighborhoods.

But enforcement of federal regulations dating to the Nixon administration has been reducing air pollution from fossil fuels and fertilizers in the valley, requiring cleaner engines for trucks and the replacement of outdated equipment on farms.

“We’ve been seeing a lot of positive trends,” said Jon Klassen, manager of the air monitoring team at the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District. At the same time, “there’s a lot more emissions coming from these fires. They’re uncontrollable. They’re very difficult to deal with.”

Research looking at air pollution levels helps explain why people like Hernandez are suffering more during fire seasons. The Climate Central analysis of San Joaquin Valley air data showed that while the number of days each year on which levels of PM2.5 exceeded federal standards declined by about 45 percent overall from 2000 to 2016, they increased by almost a third during the peak summer fire season.

In the Sacramento Valley to the north, summer fire season pollution has been responsible for about 40 percent of the days when federal standards for PM2.5 pollution were exceeded in recent years. That’s up from less than a tenth of them earlier this century, the researchers found.

Wildfires also release toxic material and chemicals that react in the atmosphere to form ozone pollution, which can hang over neighborhoods as haze. Ozone irritates lungs and throats, triggers shortness of breath and aggravates diseases like bronchitis, emphysema, and asthma.

Hernandez’s asthma doctor, Praveen Buddiga, who operates his own practice in nearby Fresno, treated patients with oxygen and medicine during September fires in the Sierra Nevada mountains, which straddle California and Nevada. He did so again following the wine country fires in October. For asthmatics, the onslaughts of fire pollution are “like pouring a little salt into the wounds,” he said.

Buddiga suggests his patients limit their time outside, drive with windows rolled up, and wear masks when smoke waves hit. Better yet, he advises them to leave the area if possible until the smoke clears.

But risks can be difficult to gauge for patients and experts who want to offer precautions. Scientists who sampled pollution from wildfires using a NASA jet reported in June that fire pollution is being “significantly underestimated” by the federal government. While fleets of mobile air monitors are deployed near fires to help government agencies project the movement of smoke waves, the network of permanent monitors is sparse.

“We have no real good way of communicating to people, ‘Hey, the wildfire smoke is really bad in these spots, and this is where you take precautions,’” said Rob Carlmark, a weathercaster with ABC10 in Sacramento whose audience stretches from Bay Area cities to Lake Tahoe at the Nevada border.

Absent local smoke pollution data, he tells viewers, “The best smoke detector is your nose.”

Lighting up to protect lungs — and the planet

Josh Bien wore a heavy pack and held a hoe in one hand. Using the other, the firefighter dripped a burning mixture of diesel fuel and gasoline on the forest floor from a spouted canister. Saplings and beds of pine needles sizzled and burned around him in a national forest in the Sierra Nevada, an hour’s drive east of Fresno.

Like smoke from suburban fires in the San Francisco Bay Area, that from large wildfires in the forest of this 600-mile mountain range can travel into the Central Valley. A spate of large fires in August and September created heavy smoke that suffocated foothills towns and drove people like Elva Hernandez indoors.

Firefighter Josh Biel ignites the forest floor during a prescribed burn in the Sierra National Forest. John Upton/Climate Central

Devastating forest fire seasons in recent years have prompted research pointing to the need for more prescribed burns like this one. They’re set and managed by firefighters and foresters and guided by computer models that predict the spread of fires and their smoke. They’re aimed at removing highly flammable undergrowth and spare the mature trees.

“You can either do it on your terms,” said Adam Hernandez, a prescribed fire and fuels management officer with the U.S. Forest Service, as gray smoke billowed around, “or you wait for that wildfire to come and it does it on its terms — and then you’re in a bad way.”

Small fires used to burn regularly through the understories of the Sierra Nevada’s forests, started by lightning and native tribes. That changed after the Native Americans were forced from the mountain range, followed by more than a century of logging and aggressive firefighting. Those activities replaced stands of large, fire-resistant trees with thickets of smaller ones, building up fuel for enormous blazes.

“When you have some of these extreme wildfires, you’re creating more harmful emissions,” said Jonathan Long, an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service. Extreme fires burn larger areas and their flames jump from forest floors to incinerate canopies, producing heavy black smoke and killing mature trees. “We think taking the medicine in small doses is a lot healthier.”

The excessive undergrowth amplified the impact of California’s recent drought — there was too little water for so many trees. More than 100 million trees may have died across the Sierra Nevada in recent years. The dead trees can provide nesting cavities and their logs create important habitat for wildlife, but some scientists fear they may also intensify fires after they topple into desiccated piles.

Trees killed by the effects of drought in the Sierra National Forest. John Upton/Climate Central

The federal government has been striking agreements with state agencies to use more prescribed burns and take other steps to better manage forests. In January, California released an ambitious draft plan to restore forests over the decades to come — through a focus on prescribed burns — with the goal of reducing pollution from wildfires.

“We’re trying to ensure that we have healthy, resilient forests that are net sinks of carbon so that they’re storing more carbon than they’re releasing,” said Russ Henly, a California Natural Resources Agency official who helped draft the plan. By 2020, the plan seeks to double the amount of land treated using prescribed burns to 35,000 acres a year.

With so many local, state, and federal agencies overseeing environmental rules and owning land in California, the state says coordination will be key. For example, the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District can prevent national parks and other landowners from conducting prescribed burns when pollution levels will be affected — which is most of the time.

Mindful of the growing danger of big blazes, the air district has become more accommodating of prescribed fires. Still, finding the money to pay for the work remains a challenge.

Some members of Congress have pushed logging as a way to ease forest fires, though that approach could have the opposite effect: Trees valued by loggers tend to be the largest and most fire-resistant. Troublesome small trees and dead ones have little value other than as fuel for power plants, and even then they’re generally too expensive to gather. Low natural gas prices have been forcing the closure of biomass power plants, which are fueled with wood.

Even if the money is found to improve forest management, climate change will likely limit the progress from improved forest management, said Christopher Field, an ecology professor at Stanford University. The fire season will continue to lengthen. Landscapes will continue to dry out. “The challenge we still face is how to get out of decades of managing forests in ways that increase, rather than decrease, fire risk,” he said.

Field oversaw a survey dealing with Sierra Nevada forests completed by 75 academics, government officials and nonprofit and industry employees. While most agreed that prescribed burns and other approaches can lock carbon into the mountain’s ecosystems, they warned it will be difficult to overcome the losses from wildfires as temperatures rise.

California doesn’t include carbon losses from forest fires when it tallies its progress toward reducing climate pollution. But amid the burning, logging, and clearing of forests from Indonesia to the Amazon and the Congo, destructive fires in the forestlands of a U.S. state that has some of the world’s most ambitious climate goals are contributing to the problem.

And, in the process, they are making people sick.

This story was produced through a partnership between Climate Central and Kaiser Health News with support from the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University.