With or without climate policies, energy prices seem set to rise. The question is, Who will get the money? Auctioned cap-and-trade gives us the opportunity to take charge of price increases and share the benefits widely — even while we safeguard the climate and stimulate local jobs. Big chances like this don’t come along often!

To see what a golden opportunity this is, we’ve got to briefly review recent fossil-fuel price increases.

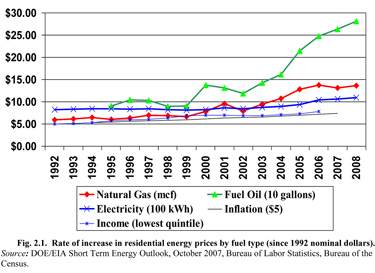

Energy prices have been rising for a decade, as this chart from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) shows. Working families have been taking it on the chin all along, as energy takes a growing share of their budgets.

Here’s ORNL:

The price increases for natural gas and home heating oil are part of an escalation in the price of carbon-based fuels over more than a decade that has outpaced the increase in purchasing power of low-income households … The mid-range EIA [U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration] price forecast foresees an increase in price of 27 percent for residential natural gas and 46 percent for propane in 2008 compared to 2004 and of 75 percent over that time frame for home heating oil.

The estimated increase in aggregate annual residential energy costs for low-income consumers … [is] over 44 percent. The impact of these rising energy costs across time can be measured for individual households in the form of rising energy burdens, defined as the ratio of residential energy expenses divided by household income. From 2001 through 2005, the most recent year for which data are available, the average residential energy burden for low-income households rose from 12.6 percent to 14.6 percent of income. For non-low-income households the average burden was 3.1 percent of income in 2001 and remained essentially unchanged at 3.2 percent of income in 2005.

Restated: As of 2005, when energy prices weren’t yet as high as now, low-income families in the U.S. were already devoting almost 15 percent of their household budgets to residential energy, more than four times as much as better-off families. High energy prices redistribute wealth from the poor to the rich, by sluicing money from people at the bottom of the income scale to the energy-company shareholders at the top.

This news is especially troubling considering how unkind the economy has been to working families of late. But who ever said that markets are automatically fair? Markets are good at some things; ensuring fairness is a job for democracy. Which brings us to climate policy.

Up to now, energy prices have not been rising because of cap-and-trade; they’ve been rising because of supply and demand. Oil and gas supplies appear tighter by the day, not just because of war and politics in oil-exporting regions, but also because the energy industry is already tapping most of the conventional fuels that are easy to extract. But if energy supplies are constrained, demand clearly is not. Consumers worldwide, especially in fast-growing economies such as China’s, are gaining purchasing power, and are using their money to buy oil.

And that’s the rub: oil and gas are in short supply; global demand is growing. The result is escalating prices. Prolonging our dependence on fossil fuels will leave us pinched in this market vise.

But placing a firm and declining cap on emissions, though it too will raise the price of energy, has peculiarly beneficial impacts. For starters, the price increases stemming from auctioned cap-and-trade might substitute for, rather than add to, market price rises.

Consider oil. Oil prices have recently been approaching $100 a barrel. Imagine that, in a North American auctioned cap-and-trade system, oil costs an extra $10 a barrel in a few years time. Over time, if consumers expect the price to remain at that level, that price increase might depress consumption by 6 percent (assuming long-term price elasticity of 0.6). In a tight market, a 6 percent reduction in demand can lead to more than a 6 percent drop in price.

The resulting oil price? Well, who knows? But it could still be something in the vicinity of $100. (I’m simplifying wildly, I know. The principle is this: prices are going up either way, with or without climate policy. They might even rise by similar amounts.)

Better still — and unquestionably — the $10 per barrel it takes to pay for carbon allowances doesn’t go to energy companies. Or it doesn’t stay with energy companies. They must give it to the public treasury, to pay for their carbon emissions permits. From the public coffers, the money will flow to public purposes — whether as citizen climate dividends, buffer payments to working families, or new community projects such as clean-energy research, bikeway investments, or green-collar workforce training. All of these things do more to stimulate economic vitality and job creation than fatter profits for energy companies.

In Cascadia, the local benefits of recirculating energy dollars will be especially pronounced, because we import most of our fossil fuels. (Only British Columbia among Cascadian jurisdictions produces appreciable quantities of oil or natural gas; no one mines much coal.) So a cap on emissions will have the effect of discouraging imports — keeping money from flying out of our local economies.

I don’t want to overstate the case. Capping emissions will constrain the supply of energy, which will raise energy prices. That’s not an accidental side effect: that’s the point. Climate pricing means raising the price of climate pollution, which means energy. But energy prices are rising anyway. Auctioned cap-and-trade lets us take charge of the increases — a rare opportunity — and ensure that the money goes to local economies, not distant moguls; working families, not energy companies; and community projects, not historic polluters.

Note: The chart and quote above are from Joel Eisenberg, “Short And Long-Term Perspectives: The Impact On Low-Income Consumers Of Forecasted Energy Price Increases In 2008 And A Cap-And-Trade Carbon Policy In 2030,” Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tenn., December 2007. This paper doesn’t seem to be online but excerpts are here (PDF).

With or without climate policies, energy prices seem set to rise. The question is, Who will get the money?

With or without climate policies, energy prices seem set to rise. The question is, Who will get the money?