The Obama administration took aim at the spiraling cost of housing when it recently released a “toolkit” for changing local zoning codes. Get rid of requirements for parking and large lot sizes, the White House urged, allow greater density and more affordable housing will follow.

The problem, at first glance, was that these recommendations appeared toothless. The federal government doesn’t control zoning codes, so how can it carry them out?

But, because of the racial discrimination inherent in these exclusionary zoning codes, it turns out that the federal government has more power to force changes to zoning rules than many (including me) realized.

Why do affluent suburbs throughout the country want codes that guarantee low-density development? The residents will tell you it’s to prevent nemeses like traffic, overcrowded schools, and loss of greenery.

But the history of zoning says something else. These zoning codes have often been adopted precisely because residents want unaffordable housing to keep out people with less money. In many urban areas, it’s the same thing as keeping out people of color.

That means the Department of Justice could use the Fair Housing Act of 1968 to force them to change. The law bans not just intentional discrimination but any policy that has an “unjustified” discriminatory effect or “disparate impact” on different racial groups (How can discrimination ever be justified? An example might be a town where low-density rules protect sensitive wetlands).

Until a century ago, towns and cities, especially in the South, could legally pass ordinances that were explicit about stopping black people from moving into white neighborhoods. That changed in 1917, when the Supreme Court ruled that practice unconstitutional by striking down such a law in Louisville.

Local governments responded by devising zoning rules that kept out African-Americans, and later Latinos, by effectively making their housing unaffordable. They allowed only single family homes with multi-car garages on large lots, guaranteeing that their neighborhoods would be fairly expensive, which in turn meant they would remain mostly white.

The connection between high housing prices and racial exclusivity is even stronger than the racial income gap would suggest, because buying an expensive house requires a large down payment, and that requires savings. The average white family has 13 times the wealth of the average black family and 10 times the wealth of the average Latino family.

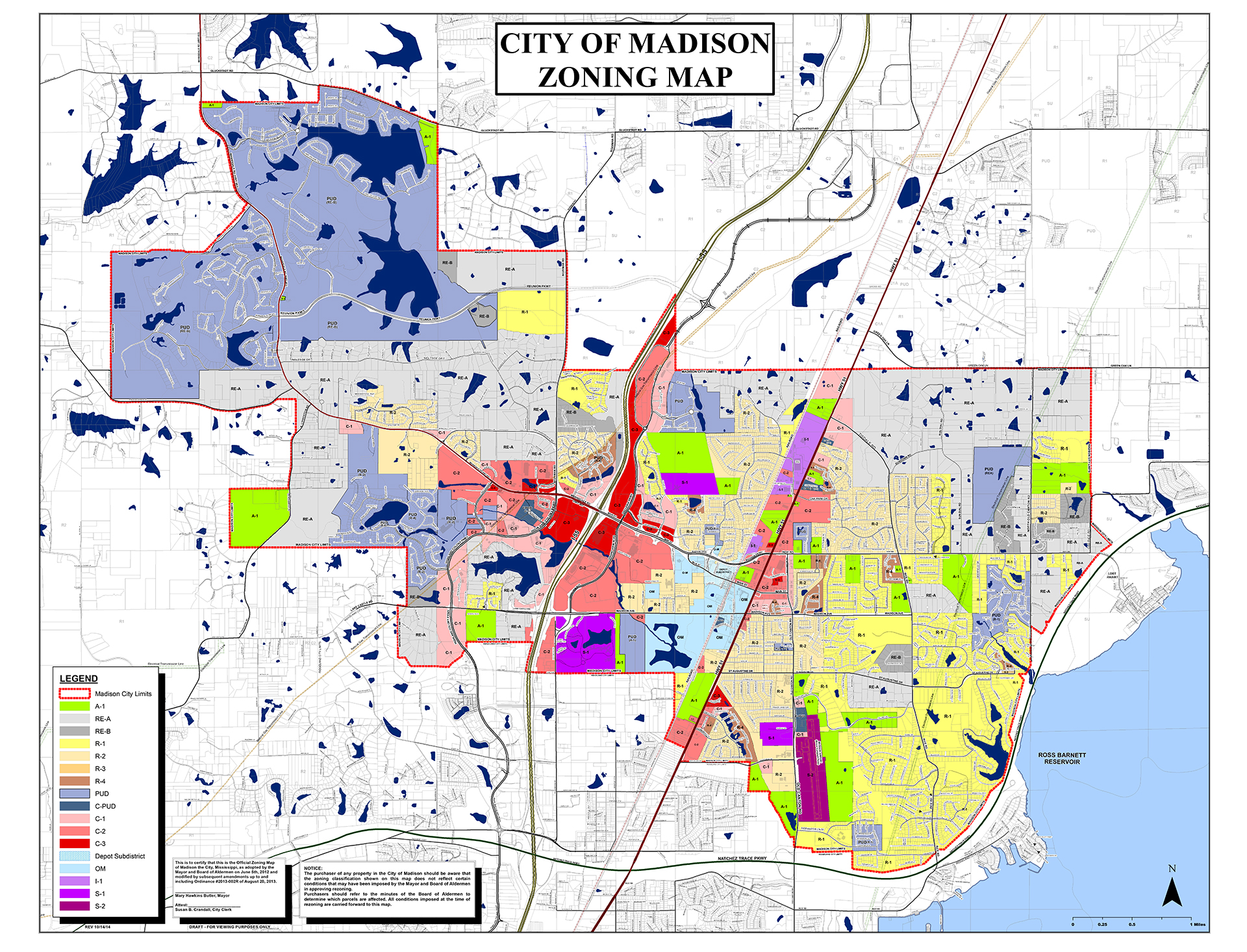

Suburbs today are rife with such exclusionary zoning. As you can see in this map, the city of Madison, Mississippi, a suburb of Jackson, has 17 different kinds of zoning districts. Only one of those designations, R4, is for multi-family housing, and it’s allowed in less than 2 percent of the city.

This mandatory low density helps to maintain Madison’s racial and economic exclusivity. The numbers reveal stark differences between the neighboring cities: Madison is 92 percent non-Hispanic white, while the city of Jackson is 79 percent African-American. In Madison, the median household income is $109,873, and 2 percent of its residents live in poverty. In Jackson, the median is $33,000, and 30 percent live in poverty. Madison’s residents paid a median monthly rent including utilities of $1,238, according to the latest figures. Jackson’s residents paid $720.

City of Madison

It’s a similar story across the country wherever you find wealthy, predominantly white suburbs from Oakland County, Michigan, outside of Detroit, to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Sometimes, suburbs pretend they’re promoting affordable housing while actually holding diversity at bay. Affluent towns create affordable housing for senior citizens or their own civil servants, like schoolteachers, so that they can take care of their existing community without letting any outsiders in.

“There are certain restrictions like having multi-family developments but only luxury housing; then you might have white residents able to live there but not African-Americans or Latinos,” says Elaine Gross, president of Erase Racism, an organization advocating for racial equity based in suburban Long Island, New York.

So if all these towns are breaking the law, why doesn’t the Obama administration just use its legal authority to force them to permit denser, more affordable housing?

The answer is that the Fair Housing Act doesn’t give the government much power to enforce the law. A federal agency cannot send out inspectors to every town to issue fines for violations. The primary solution is to sue, which is time-consuming, expensive, and subject to the whims of judges — many of whom were appointed by conservatives.

Under most recent presidents, the Department of Justice has neglected this responsibility, leaving it up to civil rights organizations to sue in some of the most egregious cases. Under the Obama administration, the Department of Justice sometimes does step in. It’s suing the town of Oyster Bay, New York, for creating affordable housing programs that favor its residents, instead of supporting affordable housing for anyone. Since Oyster Bay is overwhelmingly white, the programs assure it will remain so.

But even Obama’s DOJ has been cautious. They are walking on eggshells politically: Get too aggressive, and they might trigger a backlash from suburban white swing voters, or a crusade to defund the civil rights division from the House Republican majority.

This city-by-city approach — challenging a county here and a town there — means there’s no sweeping, countrywide change.

“It’s going to be on a case-by-case basis,” says Thomas Silverstein, associate counsel at the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, an anti-discrimination non-profit. “They can’t sue every municipality that’s engaged in exclusionary zoning at once.”

What’s needed is a system-wide solution, such as strengthening the Fair Housing Act to give the feds broader enforcement powers. It’s impossible to imagine this happening with the current Congress, of course, and any effort by the federal government to claim more control over land use would lead to legal challenges.

“We have not just an historical norm that local governments control these processes, but it’s almost become like a culture of it,” says Silverstein. “People think of local control as the natural state of affairs.”

As the Obama administration has finally come to realize, however, the shortage of housing and its drag on our economy is a national problem, and so is housing segregation. It’s time we started working on a national solution.