This story is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

There was a somewhat surprising announcement this week from a country with one of the world’s worst climate reputations: Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s office declared that his government is committed to signing on to the next major international climate accord, set to be hammered out in Paris later this year.

In a statement, the PM’s office said that, “A strong and effective global agreement, that addresses carbon leakage and delivers environmental benefit, is in Australia’s national interest.”

I have no idea what “carbon leakage” is. Presumably it’s something similar to carbon dioxide emissions, which are the leading cause of global warming. [Update: Carbon leakage is “the term often used to describe the situation that may occur if, for reasons of costs related to climate policies, businesses were to transfer production to other countries which have laxer constraints on greenhouse gas emissions,” according to the European Commission.] Regardless, the announcement is a welcome sign from an administration that was recently ranked as the “worst industrial country in the world” on climate action.

The Paris summit is meant to elicit strong commitments to reduce carbon pollution from all of the world’s leading economies, so it’s a good thing Australia is willing to play ball. The country gets 74 percent of its power from coal (that’s nearly twice coal’s share of U.S. energy generation). Australia has the second-largest carbon footprint per capita of the G20 nations (following Saudi Arabia), according to U.S. government statistics.

But let’s not get too excited. Although Abbott hasn’t yet specified exactly what kind of climate promises he’ll bring to the table in Paris, there’s good reason to be skeptical. Here’s why: In the run-up to the talks, developed countries are keeping a close eye on each others’ domestic climate policies as a gauge of how serious they each are about confronting the problem. It’s a process of collectively raising the bar: If major polluters like the United States show they mean business in the fight against climate change, other countries will be more inclined to follow suit. Of course, the reverse is also true — for example, the revelation that Japan is using climate-designated dollars to finance coal-fired power plants weakens the whole negotiating process. That’s one reason why President Barack Obama has been so proactive about initiating major climate policies from within the White House rather than waiting for the GOP-controlled Congress to step up.

So, on that metric, how are Australia’s climate policies shaping up? It looks like they’re going straight down the gurgler.

Almost a year ago, Australia made a very different kind of climate announcement: It became the world’s first country to repeal a price on carbon. Back in 2012, after several years of heated political debate, Australia’s parliament had voted to impose a fixed tax on carbon pollution for the country’s several hundred worst polluters. The basic idea — as with all carbon-pricing systems, from California to the European Union — is that putting a price on carbon emissions encourages power plants, factories, and other major sources to clean up. Most environmental economists agree that a carbon price would be the fastest way to dramatically slash emissions, and that hypothesis is supported by a number of case studies from around the world — British Columbia is a classic success story. (President Obama backed a national carbon price for the U.S. — in the form of a cap-and-trade system — in 2009, but it was quashed in the Senate.)

In Australia, the carbon tax quickly became unpopular with most voters, who blamed it for high energy prices and the country’s sluggish recovery from the 2008 global recession. Abbott rose to power in part based on his pledge to get rid of the law. In July 2014, he succeeded in repealing it.

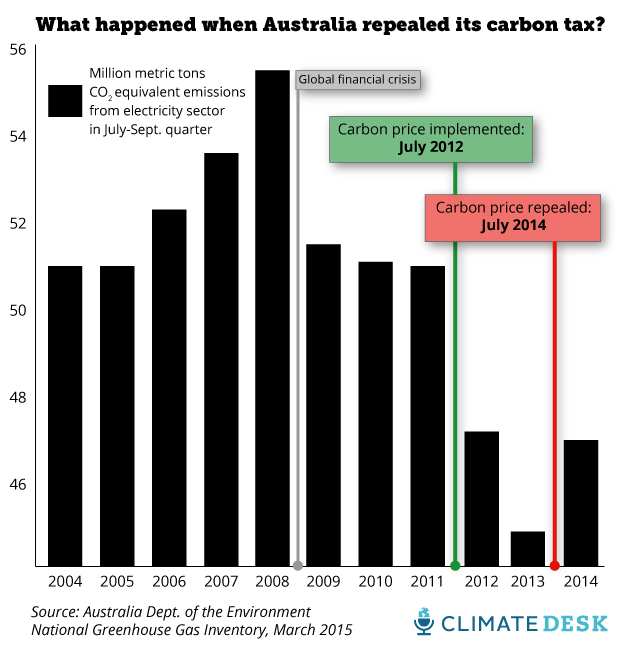

Now, new data from the Australian Department of the Environment reveal that whether or not you liked the carbon tax, it absolutely worked to slash carbon emissions. And in the first quarter without the tax, emissions jumped for the first time since prior to the global financial crisis.

The new data quantified greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity sector (which accounts for about a third of total emissions, the largest single share) in the quarter from July to September 2014. As the chart below shows, emissions in that same quarter dropped by about 7.5 percent after the carbon tax was imposed, and jumped 4.7 percent after it was repealed:

Tim McDonnell

It’s especially important to note that the jump came in the context of an overall decline in electricity consumption, as Australian climate economist Frank Jotzo explained to the Sydney Morning Herald:

Frank Jotzo, an associate professor at the Australian National University’s Crawford School, said electricity demand was falling in the economy, so any rise in emissions from the sector showed how supply was reverting to dirtier energy sources.

“You had a step down in the emission intensity in power stations from the carbon price — and now you have a step back up,” Professor Jotzo said.

… [Jotzo] estimated fossil fuel power plants with 4.4 gigawatts of capacity were taken offline during the carbon tax years. About one-third of that total, or 1.5 gigawatts, had since been switched back on.

In other words, we have here a unique case study of what happens when a country bails on climate action. The next question will what all this will mean for the negotiations in Paris.