Jerry KirkhartPigeon guillemots, a kind of puffin.

Nearly a quarter of a century after the Exxon Valdez crashed and spewed 11 million gallons of crude into Prince William Sound, one species of seabird still has not recovered from the disaster. To help it recover, the federal government is proposing to get rid of lots of American minks. Allow us to explain.

Thousands of pigeon guillemots were killed by the Valdez disaster — some coated with oil, others poisoned by it for a decade afterward. The guillemots are the only marine bird still listed as “not recovering” from the accident; the local population is less than half what it was before the spill.

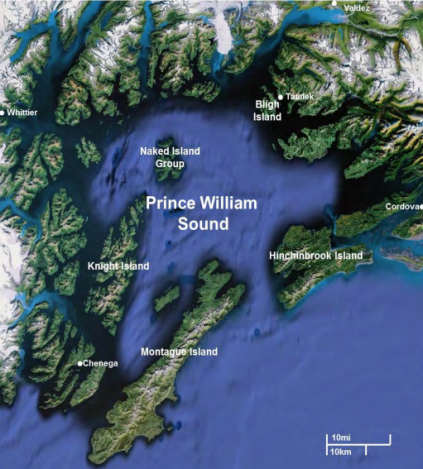

The birds used to flourish on the Naked Island group in the middle of the sound, but fewer than 100 remain there now. To boost that number back up to the pre-spill level of 1,000, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is proposing to trap most of the islands’ American minks — aquatic ferret-like creatures that feast on the birds’ chicks and eggs. If trapping doesn’t work, shooting the minks is the backup plan.

Leo-AvalonAmerican mink.

The minks are native to the region, but nobody knows for sure whether they are native to the islands in question. What scientists do know is that the islands’ mink populations skyrocketed in the immediate aftermath of the 1989 spill. “[T]he increase in mink caused pigeon guillemots and other bird species (whose nests are susceptible to mink predation) to decline significantly,” the FWS wrote in a draft environmental assessment detailing its proposal.

Figuring out how many mink to remove is “the hard part,” [FWS seabird coordinator David] Irons said, as the exact number inhabiting the cluster of islands is unknown, although their numbers are estimated to range roughly from 200-300.

By removing the mink, several other species of birds that nest on the islands would benefit as well, Iron said. Parakeet auklets, tufted puffins and horned puffins have also been on the decline in the past decades, but those birds are not on the [Exxon Valdez oil spill] Trustee Council’s list of affected animals.

“Right now Naked Island is a desert of birds — it used to be a hot spot,” Irons said, adding that the Prince William Sound used to be home to 700 parakeet auklets, whereas now only around 40 remain.

It’s hard to imagine how an oil spill would cause a mink population to explode. But Irons points out that that’s not the main concern — what’s important to the Exxon Valdez oil spill Trustee Council is that the birds “were affected by the oil spill” and it is therefore the council’s responsibility to do what it can to help them out, drawing on $900 million in civil penalties paid by Exxon.

This map shows the Naked Island group. The Exxon Valdez ran aground bear Bligh Island.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service