The Canadian tar sands, or oil sands, are much more carbon-laden than most other fossil fuels produced in North America, and their possible outsized impact on the climate is one of the primary reasons the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, which would carry tar-sands oil to Texas refineries, is so controversial.

Despite long odds as oil prices continue their dip below $50 per barrel, commercial tar-sands mining is coming for the first time to the U.S., where an Alberta company called U.S. Oil Sands has begun producing tar sands from a mine in eastern Utah.

Up to 76 billion barrels of recoverable crude oil may be locked up in deposits of thick claylike and hydrocarbon-laced sand called bitumen beneath the state’s red rock canyon country, according to University of Utah estimates. (The Canadian oil industry refers to the sticky bitumen as “oil sands,” but in the U.S., the federal government uses “tar sands,” a name the Canadian industry considers pejorative because it is used by its critics.)

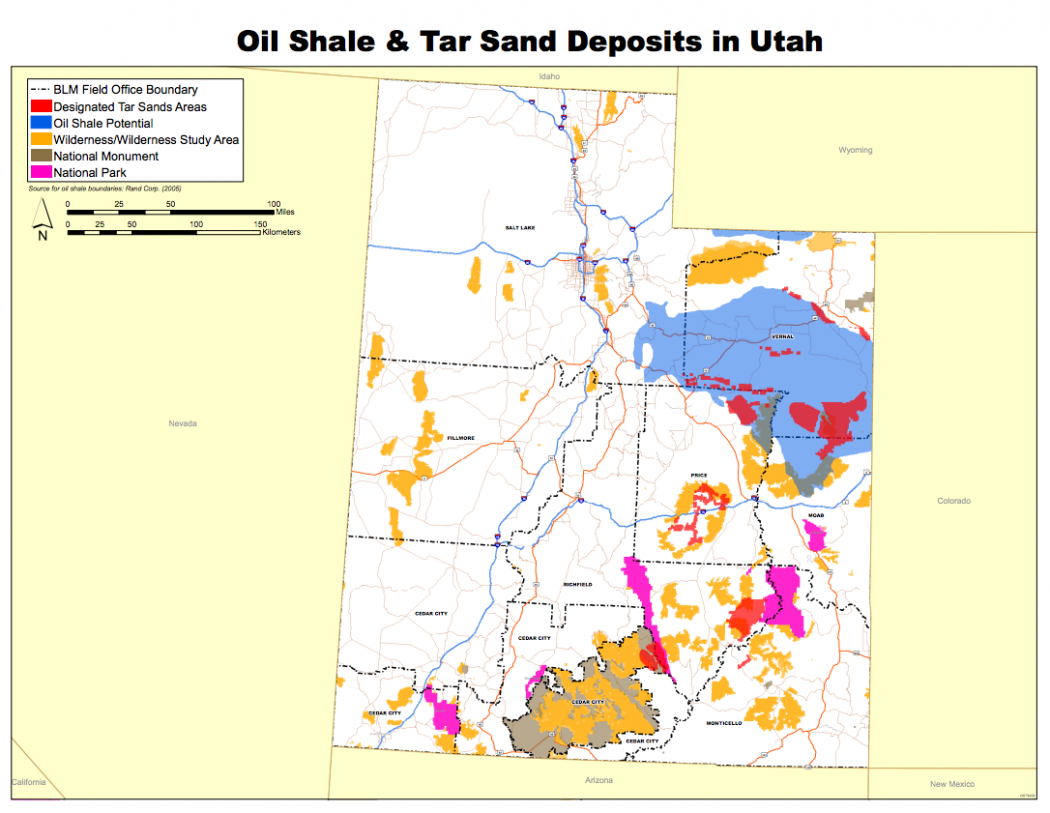

Oil price volatility makes tar-sands development in Utah — the only state in the U.S. with large deposits of it — uncertain. But if successful, it will be a historic moment in the history of oil and gas production in the U.S.

“There have been numerous attempts to develop the oil-sands resource in Uintah County, Utah, over the past eight decades,” Jennifer Spinti, a research associate professor for the Institute for Clean and Secure Energy at the University of Utah, said. “While the oil sands have been exploited commercially for use as a paving material, no company has ever produced bitumen at a commercial scale.”

If the industry does gain a foothold in the U.S., the climate implications could be significant.

In evaluating the climate impacts of Keystone XL, the U.S. State Department concluded that Canadian tar-sands production is 17 percent more carbon intensive than production of an average barrel of oil. In June, a group of 100 scientists called for a moratorium on tar-sands development, saying it is incompatible with stabilizing the climate and meeting greenhouse gas reductions targets.

But U.S. Oil Sands, which did not respond to requests for comment, is moving ahead with production, even as tar-sands producers in Canada struggle to make a profit as crude oil prices fall.

U.S. Oil Sands, which has acquired the rights to produce tar sands at mines on 50 square miles of land between Salt Lake City and Moab, Utah, plans to produce 2,000 barrels of oil per day by the end of the year, according to documents the company filed with Canadian securities regulators.

“This is a breakthrough in technology,” U.S. Oil Sands CEO Cameron Todd told the Associated Press. “If we’re able to demonstrate to the investment world that this is possible, there are many, many places where this could be done.”

The economic winds are blowing hard against the company, however.

Spinti’s 2013 economic assessment for Utah tar-sands development shows that any mine producing 50,000 barrels per day would be unprofitable even when West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil prices are above $100 per barrel. On Thursday, the WTI price was about $45.

“I expect that all oil-sands operations, both in the U.S. and Canada, will find the economic climate to be very difficult in the near term,” Spinti said.

Other challenges facing future tar-sands development in Utah include climate policy, environmental regulations, complications with land ownership, and the remoteness of some of the tar-sands deposits, she said.

“Some of the federal lands containing oil-sands resources are located in national parks, national monuments, wilderness, and wilderness study areas, so those areas would not be developable,” Spinti said. “However, the state has shown significant interest in developing the oil-sands resources on its lands and there are private landowners interested in development as well.”

From a climate perspective, any kind of tar-sands development in the U.S. would present a threat to the globe’s ability to meet climate goals, said Paul Ekins, a professor of resources and environmental policy at University College London.

Ekins published a study in the journal Nature in January showing that most Canadian tar sands would have to be left in the ground in order for the globe to cost-effectively keep global warming to 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels.

“The world is awash with fossil fuels, so if we are to get a handle on climate change, any new production of hydrocarbons will have to be balanced by reduced production elsewhere,” Ekins said. “Those who wish to produce U.S. oil sands should therefore be asked which fossil fuel production elsewhere they will substitute for.”