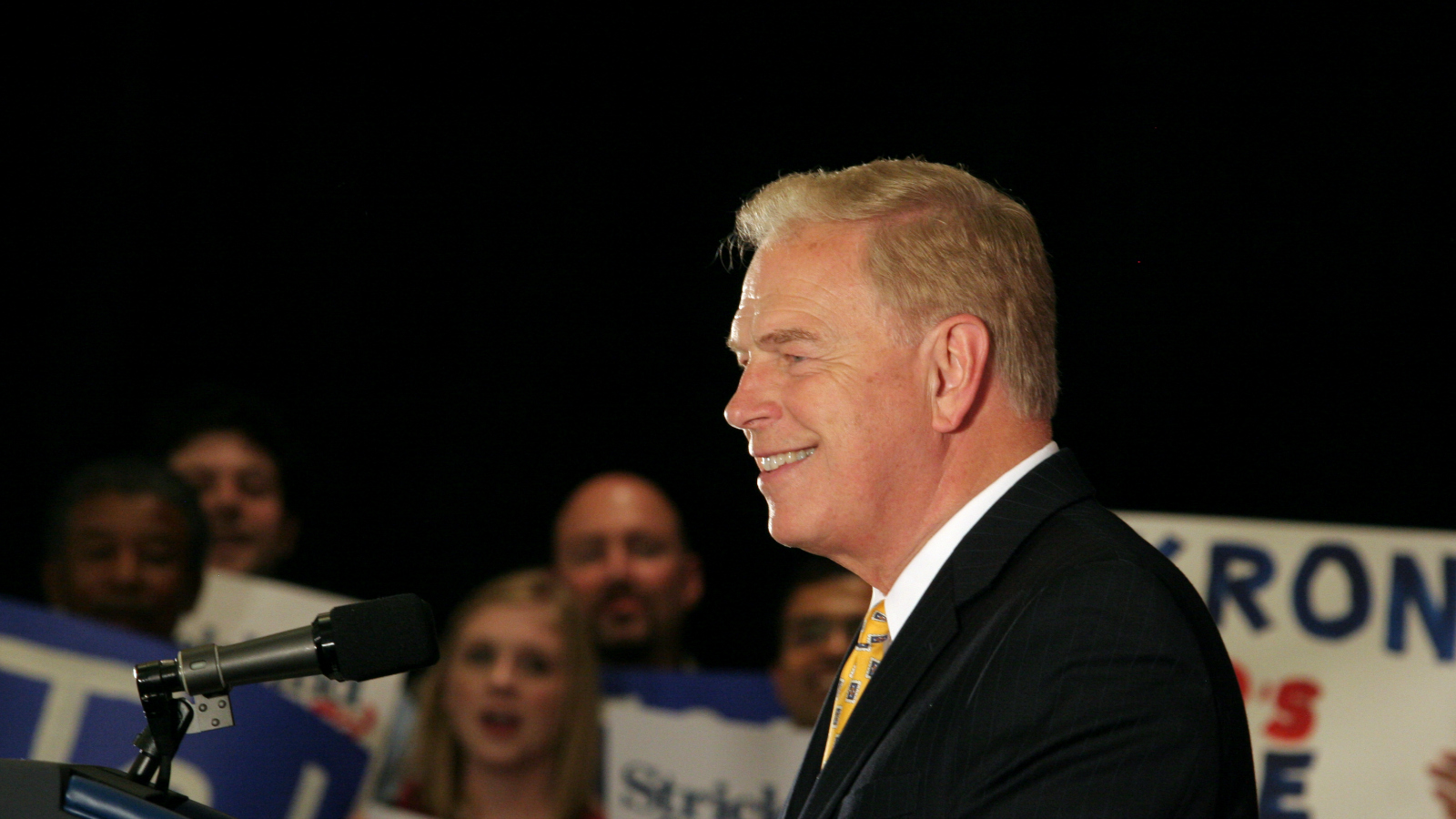

As election endorsements have been pouring in, one in particular caught your correspondent’s eye: The League of Conservation Voters is backing former Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland (D) in his U.S. Senate race. Strickland hasn’t always been a friend to the environment in the past, so will he be going forward?

LCV thinks so, and the group isn’t alone. Progressive and green activists in Ohio think so too. The reasons they give suggest not so much a personal transformation as a cultural one. Strickland’s evolution is emblematic of changes in the energy economy and Midwestern climate politics.

Strickland represented Ohio in the U.S. House for a dozen years in the ’90s and the aughts, and LCV gave him a 77 percent rating for that time. That’s certainly respectable, but it’s lower than the 90 percent–range scores typical of leading congressional climate hawks. Strickland repeatedly voted against higher fuel economy standards for automobiles. He also voted against reducing subsidies for coal and logging, and for George W. Bush’s 2005 energy bill that contained a host of pro–fossil fuel provisions, including the “Halliburton loophole” that exempts fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act. But he also cast pro-environment votes on controversial issues, such as voting against allowing more offshore drilling and against drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. As Roll Call notes, Strickland’s LCV score gradually rose over the course of his six terms in the House.

As governor from 2007 to 2011, Strickland had a strong record on clean energy. He managed to get a Republican-controlled legislature to pass a renewable portfolio standard, mandating that 25 percent of the state’s electricity be produced from renewable sources by 2025. That law helped propel the growth of the state’s clean energy sector so it supported 25,000 jobs, or 89,000 if you count jobs in energy efficiency. (Strickland’s successor, John Kasich, now a GOP presidential candidate, signed a law in 2014 that weakened and delayed the standard.)

This kind of mixed record is typical of some other liberal populists from the Midwest, like former Michigan Rep. John Dingell (D), longtime chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. These Midwestern Democrats usually support clean air, clean water, and preserving the natural areas where their blue-collar constituents camp, hunt, and fish. But their states and districts depend on energy-intensive heavy manufacturing industries, most notably the auto industry. And given their proximity to Appalachia, their energy portfolios are among the most coal-dependent in the country. Ohio has the ninth-most coal-reliant energy sector, with 67 percent of its electricity coming from coal.

But times have changed since Strickland began his congressional career. Other Midwestern Democrats now have strong records on climate change and clean energy, like Sherrod Brown, who holds Ohio’s other Senate seat and has a lifetime score of 93 percent from LCV. Progressive and environmental activists say they are confident that Strickland will pretty consistently side with them going forward.

That’s partly just because he will have a broader constituency than he did during his time in the House, when he represented a district in eastern Ohio. “When you look at his congressional district, he was in the middle of coal country,” says Sandy Thiel, executive director of Progress Ohio, a progressive advocacy group. “When he was in that district he represented it very well, and when he was governor he represented the entire state very well.”

There are other reasons too. The economics of energy are rapidly changing. Coal is on its way out for economic reasons: cheaper renewables, the fracking-led boom in natural gas, and the depletion of easily accessible coal reserves, especially in Appalachia. Coal’s share of the U.S. electricity portfolio is dropping. Three major U.S. coal companies have declared bankruptcy in the last year and a fourth is on the brink.

Meanwhile, the auto industry is not as consistently opposed to stricter fuel economy standards as it once was. After the industry was battered by the Great Recession, the Obama administration bailed it out and got its support for higher standards. “Ohio is the No. 2 automaker [after Michigan] and No. 1 auto parts maker, but we’ve seen auto manufacturers be more supportive of fuel efficiency standards, so that will hopefully have a good effect on Strickland,” says Thiel. A note of caution, though: Since the auto industry rebounded, it has become more resistant to higher fuel efficiency standards again, wrangling concessions from the Obama administration when it raised standards a second time in 2011.

Wind and solar power are growing by leaps and bounds at home and abroad, creating opportunities for jobs building wind turbines, solar panels, and their component parts. States with a manufacturing infrastructure and workforce are well-positioned to benefit. With major growing economies such as China and India having committed in Paris last December to dramatically expand their renewable energy generation, there is even more rapid growth to come. According to local green activists, that’s changing the politics of energy in the Rust Belt. “The world wants clean energy,” notes Jen Miller, director of the Sierra Club’s Ohio Chapter. “One hundred ninety countries signed the Paris climate agreement and, of course, that’s an economic opportunity.” Ohio isn’t the only Rust Belt state taking notice: In Michigan, both Democrats and Republicans, including GOP Gov. Rick Snyder, are backing clean energy development.

Miller also says that as the public becomes more aware of the effects of climate change, that’s shifting the politics of energy in the Great Lakes region. As researchers at Ohio State University point out, “increased rainfall right here in the Great Lakes region can flood sewer systems and cause contamination of lakes, streams and other supplies of drinking water, which can lead to harmful algal blooms and water-borne illnesses.” This is already a major problem in Michigan. “One of the things that’s happening in Ohio that’s very visceral, in terms of climate change impact, is what’s happening to our inland lakes,” says Miller. “We have massive flash flooding across the state now, major water quality issues. One-third of our beaches across the state last year got closed because of high bacteria levels.”

Strickland’s campaign declined an interview request from Grist, but sent a statement from campaign spokeswoman Liz Margolis framing progressive climate politics as part of a populist stance: “Energy and environmental issues offer another powerful example of how Ted Strickland is a fighter for working people. He grew up in Appalachia and cares deeply about this community — and he understands how market forces and environmental factors have impacted and changed Ohio’s energy industry over a long period of time. … In the Senate, he will continue to stand up for working people and to ensure that Ohio is positioned to take advantage of all the benefits that the clean energy economy can bring.” This is very different from the kind of language we hear from coal-state Democrats like Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and oil-state Democrats like former Sen. Mary Landrieu of Louisiana, who talk about protecting their local economies from the federal government’s meddlesome threats to cap carbon emissions or regulate fossil fuel extraction.

Of course, when LCV makes an endorsement, it is factoring in both a candidate’s record and that of his or her opponent. Strickland is challenging Sen. Rob Portman (R), who has a lifetime LCV score of 20 percent and a score in the Senate of just 9 percent. Portman has sided with the fossil fuel industry on all of its major priorities, such as voting in favor of the Keystone XL oil pipeline, in favor of making it easier to build liquefied natural gas export terminals, and against closing the Halliburton loophole. He also voted to overturn the Clean Water Rule, which clean water advocates say is important to Great Lakes restoration. “In the last six years alone, Portman has cast over 60 votes to prioritize fossil fuels over clean energy, against action on climate change, to undermine and weaken protections for our clean air, water, lands, wildlife, and public health – standing up for his polluter allies instead of Ohio families,” writes LCV Legislative Director Sara Chieffo in an email to Grist. Part of what LCV is doing is simply boosting the candidate it thinks is better in a close race. Polls have Strickland up by a point or two.

Portman’s campaign counters by pointing out that he wrote legislation to protect tropical forests in 1998, and last year he cosponsored bills to protect drinking water and the Great Lakes. Portman also cosponsored a bipartisan energy-efficiency bill, and in 2013 LCV President Gene Karpinski praised it and called for its passage. A version of the bill was signed into law last year. “Funny that the League of Conservation Voters clearly forgot the praise and endorsements they gave Rob Portman for his bipartisan efforts on conservation through the years,” says Portman spokeswoman Michawn Rich in an email to Grist. The campaign also contends that Portman’s pro–fossil fuel stances benefit American consumers and workers. “The bottom line is, Rob is a leader on pursuing all-of-the-above energy policies to reduce prices, promote conservation, protect national security, and create jobs right here in Ohio,” Rich said.

But LCV and environmental activists in Ohio believe not only that Strickland would be more on their side than Portman, but that Strickland would be a consistent vote for climate action and clean energy. Their understanding of politics — that an elected official’s actions reflect the changing conditions and incentives in his or her state, not just his or her personal beliefs — is shrewd. And the incentives are moving in a more pro-climate direction for progressive Midwestern politicians.