I wrote a post yesterday about the (dumb) fight between those focused on cleantech innovation and those focused on cleantech deployment. I want to follow up today by engaging with some specific arguments from an enthusiastic innovation supporter and show where I agree and where I don’t. (It’s more exciting than it sounds.)

The arguments are mainly found in this post, written by Matthew Stepp of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. In it, he makes the case for better innovation policy, a cause I support wholeheartedly. But there is an implication in the post — a point made more explicitly by Stepp in other posts — that I disagree with. Let’s take a look.

We can break the typical energy innovation argument down into three stages.

Stage one: The innovation pipeline is busted

Stepp begins by pointing out the Department of Energy has a somewhat muddled mandate — environmental cleanup, security of the nuclear arsenal, and overseeing most U.S. energy research — which has prevented it from being an effective tool of energy policy. Consequently, “energy deployment policies are largely conducted through the tax and regulatory code, including EPA mandates on power plant emissions and production tax credits, and not through the DOE.”

Since DOE has no particular experience or expertise deploying clean energy, lots of stuff never makes it out of the agency’s labs. “Energy research as a whole is no different,” writes Stepp, “and runs into significant market barriers including uninterested utility markets and a lack of initial customers for new innovations.”

Stepp concludes, sensibly, that “significant work needs to be done to connect DOE’s built-out research institutions and capabilities to markets and deployment.”

So that’s stage one: The early part of the conveyor belt I discussed yesterday is broken. I agree!

Stage two: We really need cleantech innovation

Stepp then clarifies why this disconnect between research and markets matters so much. It is entirely plausible that the U.S. can get to its near-term carbon goal — 17 percent reductions from 2005 levels by 2020 — with current clean-energy technology. But getting to our long-term target — 80 percent reduction by 2050 — will require “significant innovation, including breakthroughs like new battery chemistries and affordable, higher energy converting solar panels.”

Now, I think innovationeers have always been needlessly provocative when they say that it would be impossible to meet our long-term target with today’s technology. It assumes, among other things, that carbon reduction is purely a technological problem. But there are other levers of social change — policy, economics, and behavior — that can be brought to bear on the problem. If technology is arbitrarily frozen at today’s level of development (and how could that ever happen, by the way?), it just means we have to push correspondingly harder on the other levers. It would make the undertaking much more arduous, and success even more unlikely than it currently is, sure. Social and behavioral change are difficult, in some ways more difficult than technological change. But nothing is impossible.

Nonetheless, it’s fair to say that as carbon reductions cut deeper and deeper, it will become correspondingly more difficult, expensive, and politically contentious to achieve them with today’s technologies. And it’s fair to say that most people, including most climate hawks, underestimate the scale of the challenge. So yeah, cheaper, more powerful low-carbon technology, whether it comes in the form of incremental advances or the much-balleyhooed “breakthroughs,” will make the undertaking easier. Axiomatically.

Therefore, stage two: It is important to devote time, attention, and money to building an innovation ecosystem that reliably carries new ideas from the lab to robust market success. I agree!

Stage three: what innovation gets, it must take from deployment

Here’s where I get off the bus. Stage three of the argument stipulates that there is a finite pool of time, attention, and money devoted to clean energy and concludes that what gets spent on deployment comes at the expense of early-stage innovation. (This is mostly absent in Stepp’s latest piece — to its credit! — though not from other pieces of his.)

If this is true, then innovation is in competition with deployment and those who champion innovation must make a case against deployment, a case for why less time/attention/money should be spent on it (and correspondingly more on innovation).

And it certainly seems like a lot of innovationeers have made this their mission: to crap all over existing and proposed energy policies that are not innovation policies (and existing green groups that are not focused on innovation). It’s what has irked people from the moment the original Breakthrough Douchecanoes paddled onto the scene: that they view other climate hawks as their enemies.

So is it true? Is there a zero-sum competition between innovation and deployment? As I argued yesterday, I don’t think so.

Now, it is true — again, axiomatically — that there is a limited pool of public funds. It’s especially true these days, given D.C.’s counterproductive mania for spending cuts. But I think it’s a misreading of the political economy to think that those cuts are being made according to any rational assessment of spending needs, or that it is savvy for recipients of that spending to angle against one another for scraps.

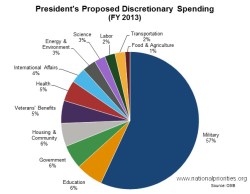

National Priorities ProjectClick to embiggen.

Consider this analogy: The U.S. budget includes a limited pot of what’s called “discretionary spending,” which is spending that’s not mandated by law. Over half of it goes to the military. A tiny percentage is spent on the earned income tax credit. Another tiny percentage is spent on Pell grants. Both policies are intended to help fight poverty. There are arguments about which is more effective. Does it follow that fans of the EITC should deride the effectiveness and appropriateness of Pell grants? Is that the best way to get more money for the EITC?

I hope it’s obvious that the answer is no. To squabble over pennies is to accept that the larger spending picture is rational and appropriate. It is to argue within a constrained space, the borders of which were drawn by opponents of social spending. The problem for anti-poverty advocates is the massive unbalance in discretionary spending, how much goes to the military and how little goes to social priorities. The problem is that the U.S. political system has deemed poverty and income inequality appropriate trade-offs for massive gains at the top of the income ladder.

That is the bigger fight. Both the EITC and Pell grants will benefit if that argument is won. And it is more likely to be won if anti-poverty advocates speak with one voice.

The same is true for advocates of sustainable energy. Right now, an absurdly small amount of time/attention/money is spent on shifting to low-carbon energy. This is, for the most part, a hangover from a time when fossil fuels were cheap and climate change but a faint rumor. It persists due to the extremism and intransigence of the Republican Party, which, thanks to quirks of America’s system of government, has almost total veto power over policy, especially federal policy. Republicans are assisted in this matter by “centrist” Democrats from fossil-fuel-heavy states.

Innovation fans will not make friends of conservatives (or “centrists”) by joining their derision of today’s clean-energy deployment policies, or their derision of carbon-pricing proposals. They will merely serve as useful idiots in the larger effort to defund and suppress sustainable energy. The strategy of denouncing environmentalists, proclaiming your commonsense bipartisanship, and seeking partners across the aisle is fruitless. It is maladapted to current political realities in America.

The larger and more consequential fight, for both innovation and deployment advocates, is the fight to make the transition to clean energy a top national priority. Innovationeers can and will build one coalition and push for one set of policies; deploymenteers can and will build another coalition and push for another set. But they are soldiers in the same army, facing the same enemy. Attempts to define the former as a “new paradigm” and the latter as crusty, backward-looking green idealism — to capture market share by punching hippies — is destined to backfire. It’s a parlor game for media-hungry narcissists.

Clean-energy innovation requires active government intervention and an appreciation of the scale of the climate challenge. Clean-energy deployment also requires active government intervention and an appreciation of the scale of the climate challenge. Meanwhile, active government intervention is under attack (discretionary government spending is shrinking) and very few people in the federal government give a tinker’s damn about climate change. Fighting over deck chairs on the Titanic might be a road to personal glory, but from a humanitarian perspective, we’d all be better off trying to avoid the friggin’ iceberg.