This story has been updated.

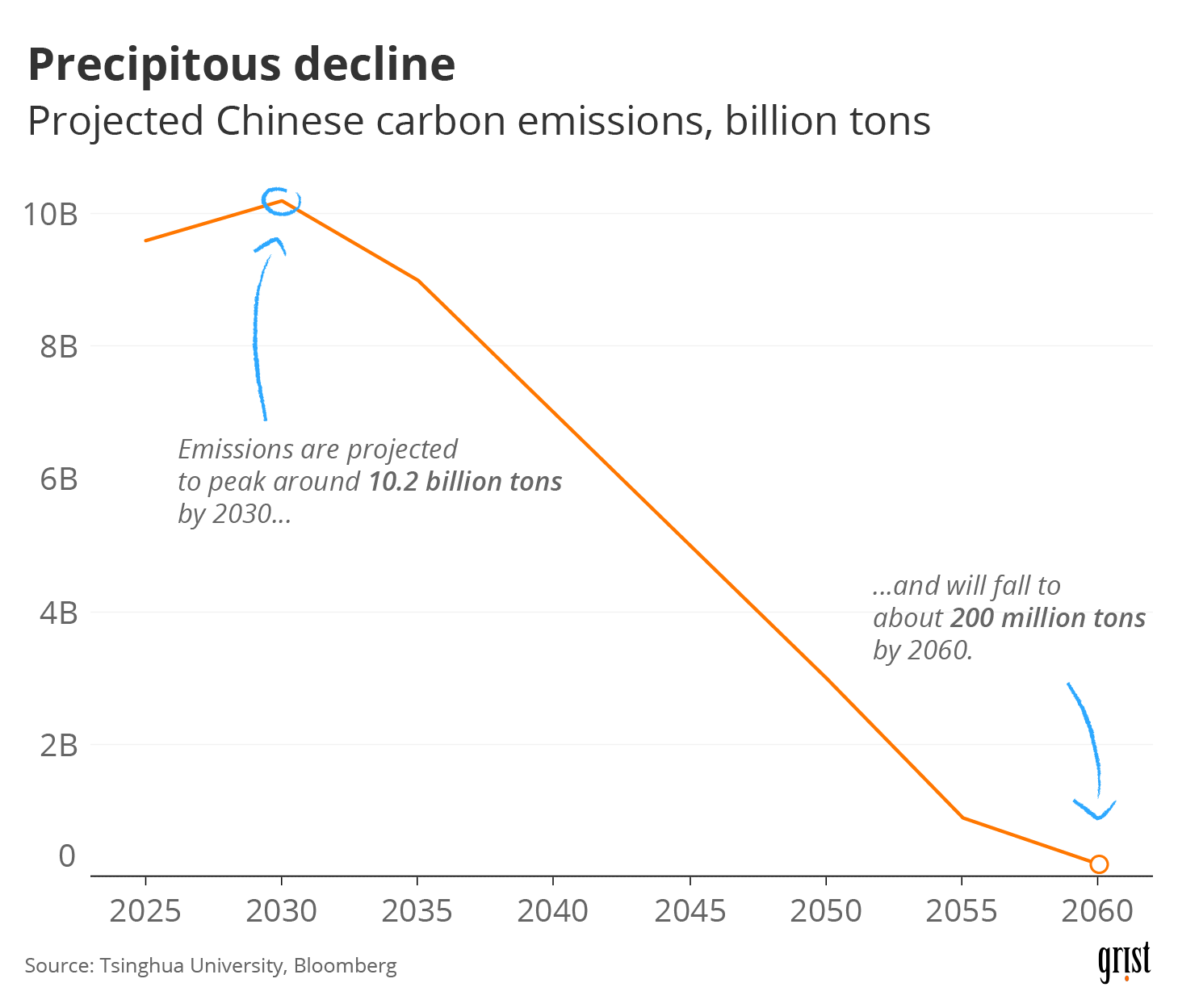

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s recent announcement that his country aims to reach peak carbon emissions before 2030 and become carbon-neutral by 2060 has raised a lot of questions: Was it a serious commitment, or a geopolitical maneuver meant to outshine President Trump? Does it exempt China’s financing of dirty energy projects in other countries? Most importantly: How will the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, which is still building new coal plants, achieve such an ambitious goal?

Varun Sivaram, a senior research scholar at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, said he cannot begin to express how gargantuan a transformation it would be.

“It would be the most herculean thing ever accomplished in human history,” he told Grist completely earnestly. “If the United States were to go to net-zero by 2050, it would be great, but it would be far less impressive than China going net-zero by 2060.”

In 2018, China emitted twice as much CO2 into the atmosphere as the U.S. did. To go net-zero, its economy and energy system would have to undergo changes on a different order of magnitude than any other country.

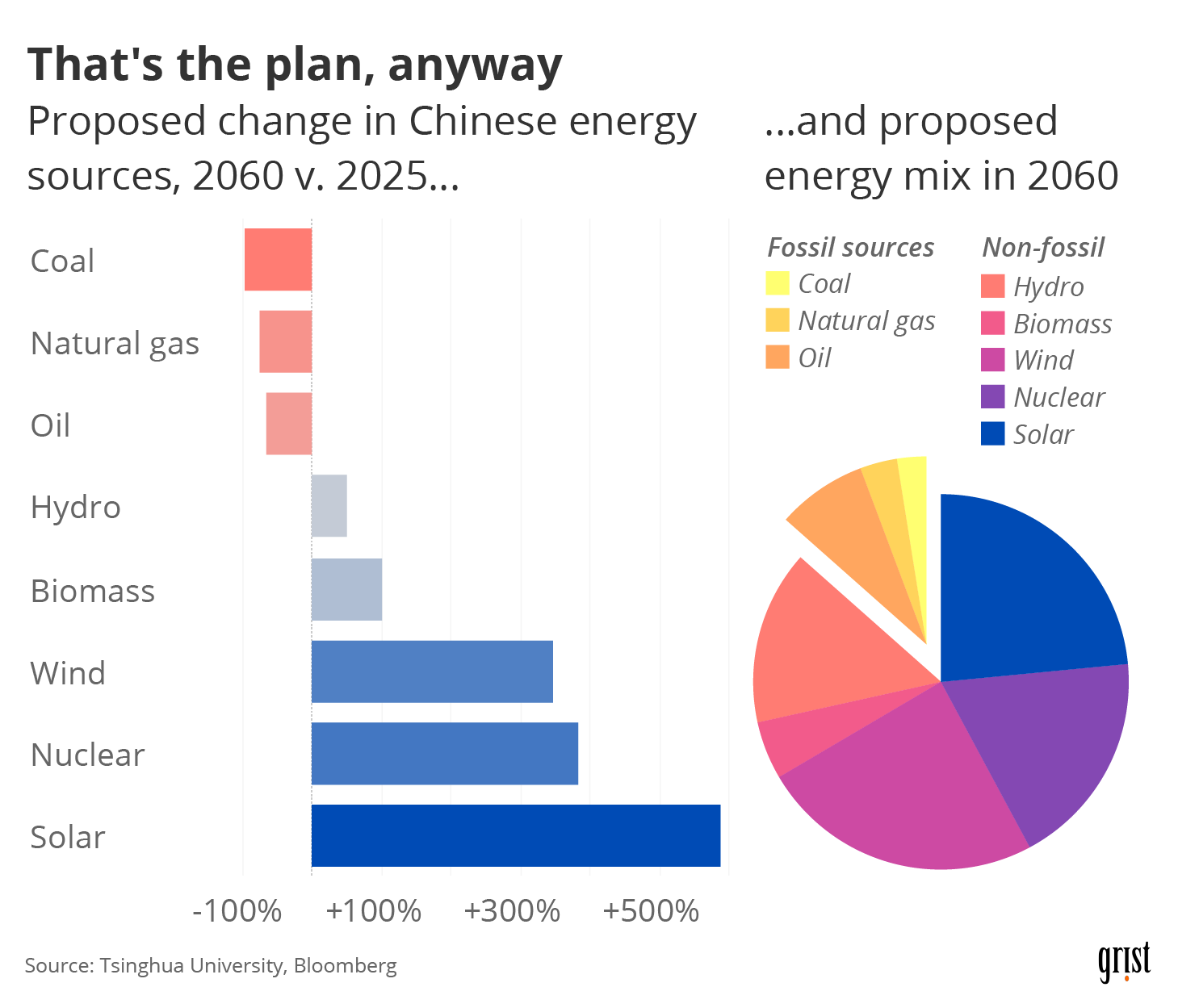

While it’s still unclear how serious China is about this target, or what its plans are in other countries, answers to the “how” came to light earlier this week with the release of a blueprint for the country’s energy transition. Tsinghua University’s Institute of Energy, Environment, and Economy, which works closely with the Chinese government’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, released a report outlining how the country’s energy mix will change by 2060. And the changes are huge.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

“What it’s committing to is a level of infrastructure build-out in energy that the world has never seen,” Sivaram said. “And if it weren’t China, I wouldn’t believe it.”

The researchers project a staggering 587 percent increase in solar energy generation between 2025 and 2060. This explosive growth is in line with Sivaram’s research — he expects solar to become the number one energy source in the world during the second half of this century.*

The roadmap also sees nuclear generation in China increasing almost five-fold — an impressive feat, but one that Sivaram does not think is unrealistic considering China’s track record of scaling up nuclear projects and its early investment in new, advanced nuclear technology.

So there’s a chance that China can pull this clean energy build-out off. But what about achieving its 2060 target? That all depends on what China decides to do with coal. The country is still digging it out of the ground and planning to construct new coal-fired power plants, which won’t be paid off until 2050 at the earliest. In a webinar about the energy blueprint over the weekend, the director of Tsinghua’s institute, Zhang Xiliang, confirmed that coal-fired electricity won’t be phased out until around 2050.

To Sivaram, that’s “horribly unrealistic.” If China’s energy mix is full of coal until 2050, the entire energy system, as well as coal-dependent communities and local economies, will have to undergo a dramatic transformation in just 10 years. He said there is no viable pathway for China to build all of its planned new coal-fired power plants and still achieve carbon neutrality in 2060.

While the Tsinghua researchers expect coal to be phased out of electricity markets by 2060, that doesn’t mean they see it disappearing altogether. They still see coal, oil, and natural gas generating about 13 percent of the country’s energy, and expect China to still emit 200 million tons of CO2. That’s about 3 percent of the United States’ carbon emissions in 2018.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

These numbers likely account for industries that are especially difficult to decarbonize, like steel and cement production, air travel, petrochemicals, and fertilizer. Remember, this is a net-zero target, meaning China aims to take as much carbon out of the atmosphere as it puts in. To zero-out the CO2 from remaining fossil fuel sources, the country will need to scale up carbon capture and storage technology.

Ultimately, no one can judge how serious China is about cleaning up its contribution to climate change based on a promise in a speech. But that may change later this month, when the country is expected to lay out the broad strokes of its energy plans for the next five years.

“China should get some credit for making this target,” said Sivaram. “But the proof of the pudding will be in the eating. And if they continue to build out the coal plants, they should get negative credit.”

Correction: A previous version of this story said that China would “have to build more solar every single year for the next 41 years (including this year) than the entire world built in 2019.” That estimate may not be accurate due to uncertainty about how China calculates solar generation.