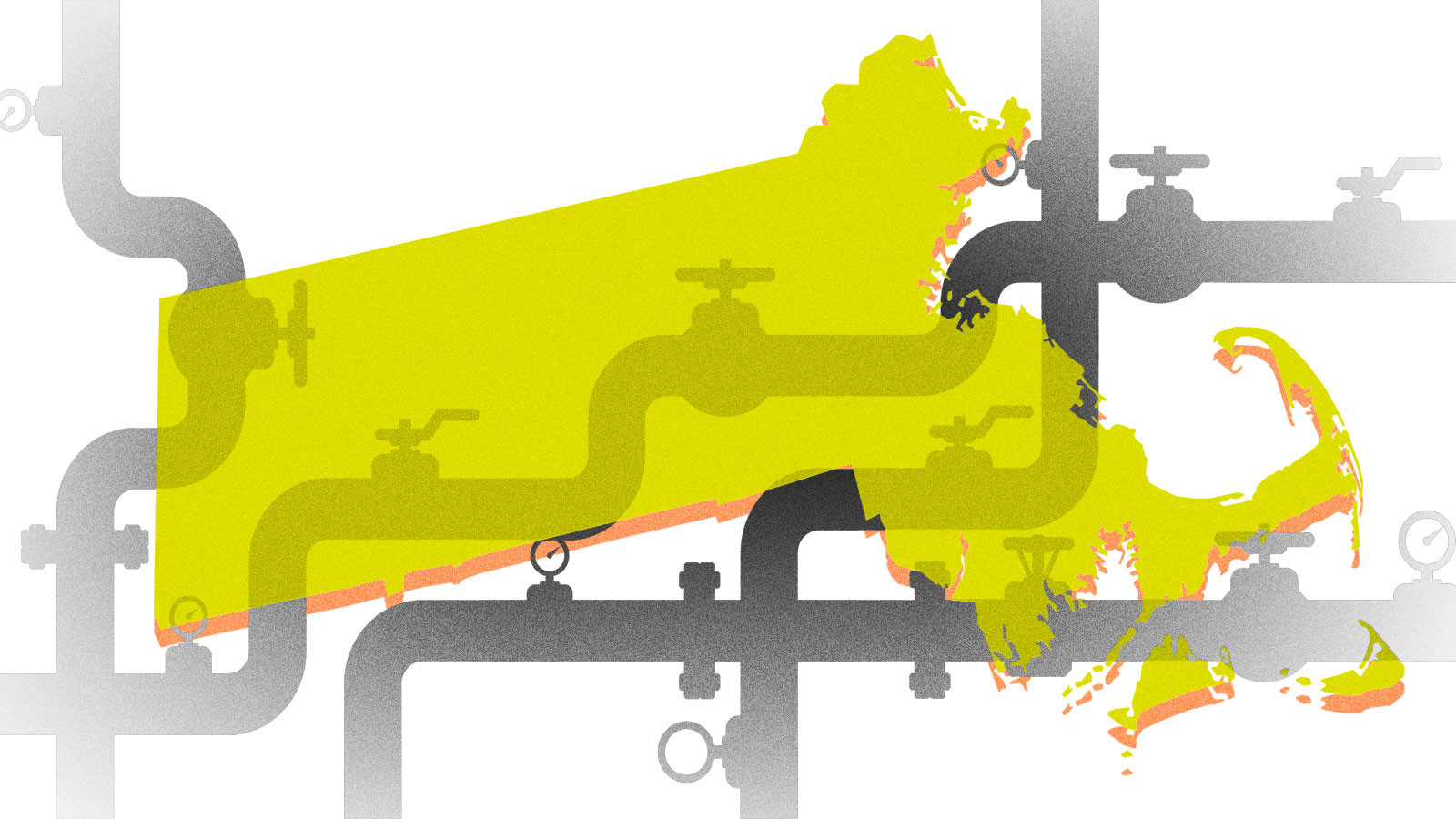

Massachusetts may be a climate leader in the U.S., with a goal to reduce economy-wide emissions in the state to net-zero by 2050, but it will face a major obstacle along the way: More than 1.3 million of its households make it through those cold New England winters by burning natural gas. Roughly one-third of the state’s emissions come from the fuels burned in buildings for heating, hot water, and cooking.

Now the state is responding to pressure from its attorney general, Maura Healey, to take a look at what the path to net-zero in the building sector might look like, particularly for the gas companies whose entire reason for existing could be eliminated in the process. Last week, the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities (DPU) officially opened a new proceeding to start guiding utilities into a decarbonized future while protecting their customers. As the number of people using the gas system shrinks over time, the cost of maintaining reliable service for remaining ratepayers could balloon.

“It’s a really complicated set of issues as you look at what’s going to be happening on the gas side as people peel off,” said Susan Tierney, a senior advisor and energy expert at the Analysis Group, an economic consulting firm. “There’s real trade-offs about affordability of supply, safety of service.”

The Massachusetts DPU joins regulators in California and New York, and now Colorado, who have all initiated similar investigations into these trade-offs and the future of natural gas in their states.

To aid in its inquiry, the DPU is requiring gas distribution companies in the state to jointly hire an independent consultant who will review two climate “roadmap” documents the state plans to release for various sectors later this year. The consultant will then analyze the feasibility of the proposed pathways in those roadmaps and offer additional ideas for how each company might comply with state law, using a uniform methodology. Ultimately the consultant must produce a single, comprehensive report of their findings for all companies. By March 2022, the companies are required to submit new proposals with “plans for helping the Commonwealth achieve its 2050 climate goals, supported by the Report,” for the DPU to review.

Tierney called this a “clever approach,” since often in utility rulemakings, each stakeholder will hire its own expert and use its own set of assumptions, leading to a data war of sorts where it’s hard to know whose numbers to go on. In this case, the DPU, utilities, ratepayers, and environmental advocates will at least have a common set of facts on which to base discussions.

But it’s also possible this approach will limit which solutions make it onto the table. Audrey Schulman and Zeyneb Magavi, co-executive directors of the Massachusetts–based environmental nonprofit HEET, applauded the new inquiry, but they are concerned that the process it outlines will result in a one-sided picture of what’s possible, and could stymie more creative solutions. “I think they were focused on ensuring the process is uniform and fair between gas companies,” said Magavi. “What I hope they are not missing is the idea generation that they could get from an engaged and open process.”

Magavi and Schulman are the masterminds behind a particularly innovative solution to decarbonize the gas system that they believe will benefit utility companies and customers. They propose that instead of overseeing the gas system, utilities could transition to overseeing what they call a “thermal grid,” made up of “geothermal microdistricts.” These would be clusters of homes that with geothermal heating systems, which run on electricity and use the near-constant temperature beneath the earth’s surface as a heat source. The systems could all be linked together to improve efficiency, forming the aforementioned “thermal grid.”

Geothermal systems have high up-front costs, but if the utility owned and operated the equipment as they do gas pipelines, that could offer them a way to stay in business in a carbon-constrained economy. Instead of replacing old gas lines with new ones, which could keep ratepayers on the hook for fossil fuel infrastructure far into the future, the utility could replace them with geothermal piping. HEET has successfully convinced Eversource, the largest utility in Massachusetts, to test the idea out with a pilot project. Last Friday, the DPU officially approved Eversource’s request to do so. The duo hope that the project will be developed in time for Eversource to collect a season’s worth of data before it submits its plan to the DPU.

The new proceeding won’t be entirely insular, as gas companies are required by the DPU to seek stakeholder feedback on both the report and their plans. When Grist reached out to Eversource and National Grid, another large Massachusetts utility company, earlier this year about how they see their role in a low-carbon future, they touted a slate of possible solutions, including putting renewable natural gas or hydrogen into their pipelines, and testing out geothermal districts. Both companies said they welcomed the attorney general’s call for an investigation into the transition.

In a statement to E&E News, Massachusetts Attorney General Healey said her office was “grateful to the DPU for taking this necessary next step.”

“This investigation is nation-leading and will allow Massachusetts to plan ahead and make the policy and structural changes in the natural gas industry we need to ensure a clean energy future that is safe, reliable, and fair for all of our customers,” she said.