It may be Arbor Day, but it’s generally a tough time to be a tree lover. That’s according to the latest edition of The World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Review, which found that millions of trees were removed in 2021, potentially putting global climate goals at risk.

“We’re losing a lot of forest cover,” said Mikaela Weisse, Deputy Director of Global Forest Watch, or GFW. “That’s definitely alarming, especially given all the commitments and attention towards forests.”

The report, which is released by WRI annually, looks at global forest data and tree cover loss. According to Elizabeth Goldman, Global Forest Watch’s senior GIS research manager, the group was particularly interested in this year’s numbers. Last November at United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP26, 141 countries signed the Glasgow Leader’s Declaration on Forests and Land Use committing to “halt and reverse forest loss by 2030.”

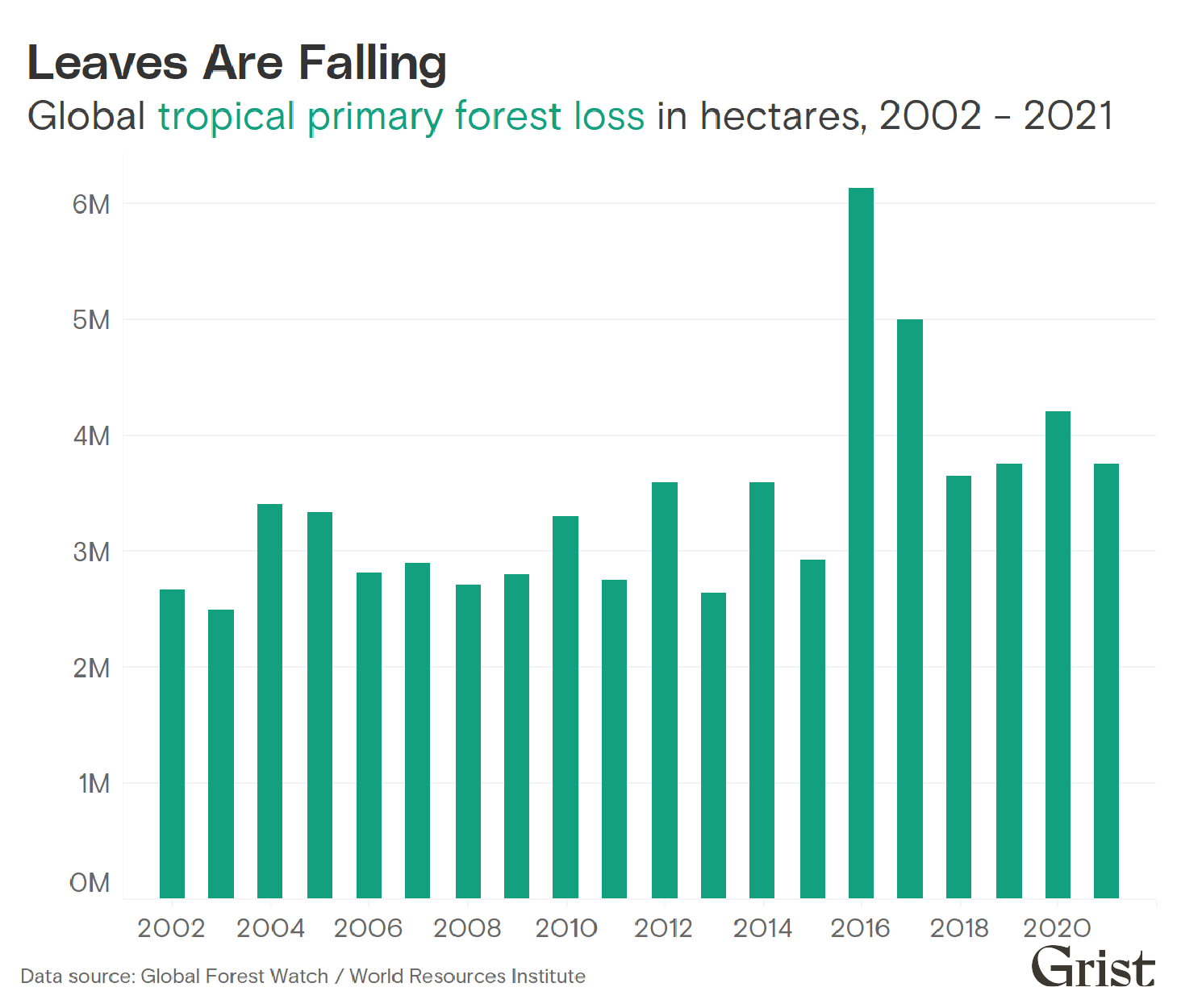

But despite those promises, the group found that the world’s pristine forests were destroyed at a “relentless” rate in 2021. The latest analysis highlighted old-growth forest loss (also known as “primary” forest loss) in the Tropics as an area of particular concern. Last year, the world lost an estimated 3.75 million hectares — the carbon equivalent of India’s total annual fossil fuel emissions — of tropical rainforest.

But raw numbers are only part of the story: When it comes to tree loss, the type of forest matters too. Tropical primary forests, for example, are critically important both in terms of maintaining biodiversity and removing and storing carbon from the atmosphere. While boreal forests — those found throughout the U.S. and Russia — have experienced tremendous losses due to wildfires, 96 percent of tropical forest loss is due to human-caused deforestation. Additionally, there is evidence that boreal forest loss can be temporary while tropical forest loss is often permanent.

The report wasn’t all bad news.

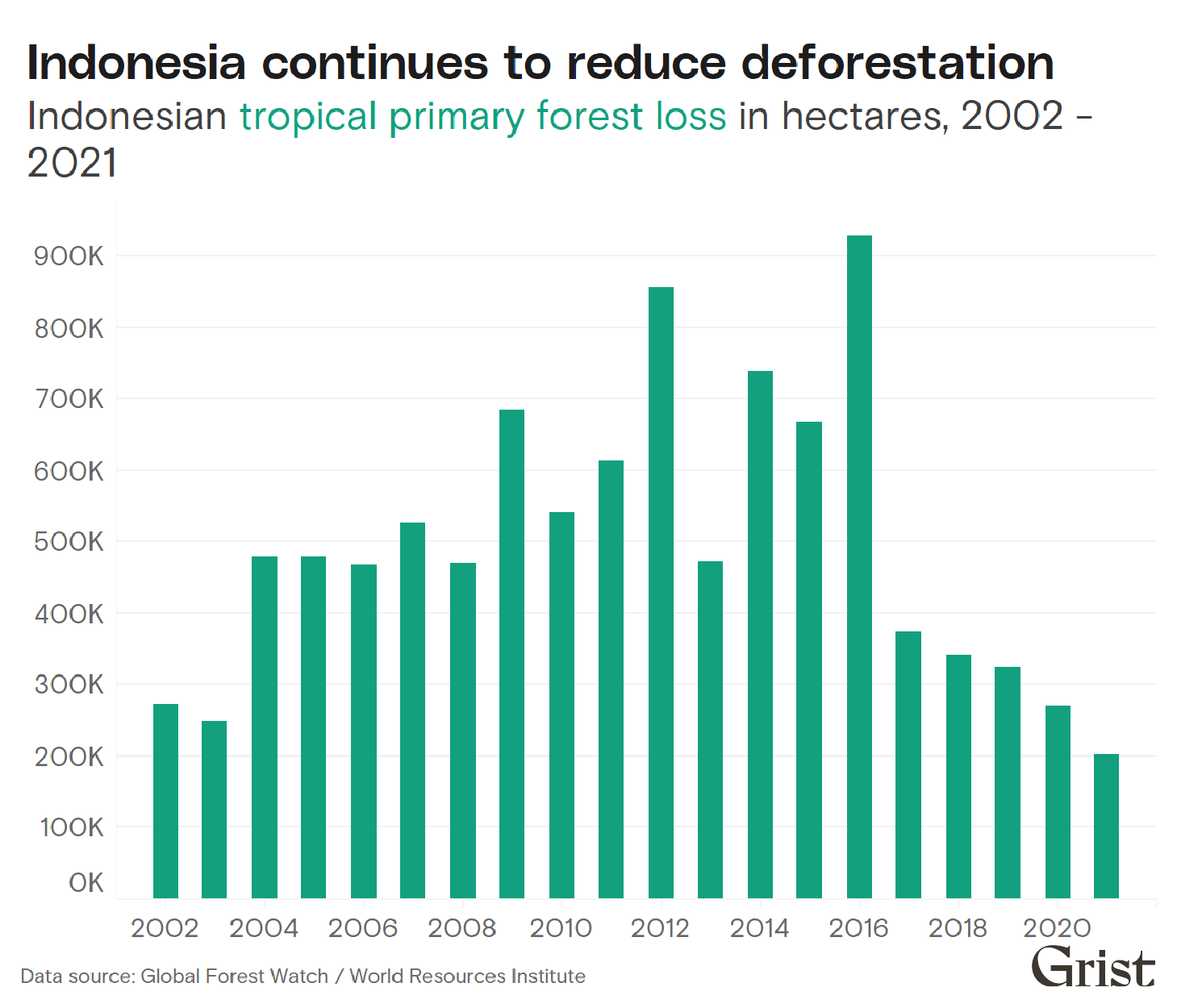

For the fifth year in a row, Indonesia significantly cut its tropical tree loss, reducing its tropical forest loss by 25 percent from 2020 to 2021. Some of that credit goes to the government, which enacted new forest conservation measures following massive forest and peatland fires in 2015 that burned over 600,000 hectares of land. The country’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry increased the country’s fire monitoring capacity, enacted a permanent moratorium on the conversion of tropical primary forest and peatland to palm oil plantations, and, in conjunction with the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, strengthened the palm oil harvesting certification requirements.

Because the palm oil industry drives so much of Indonesia’s tropical deforestation, those crackdowns have been highly effective at reducing the country’s forest losses in recent years. Weisse compares Indonesia’s success to a similar policy enacted in Brazil in the early 2000s: “The Amazon had a big decline in deforestation at that time, in part because of things like the soy moratorium,” she explained. “Soy expansion was no longer permitted to clear forests, but also there was better enforcement of the rules that were on the books.”

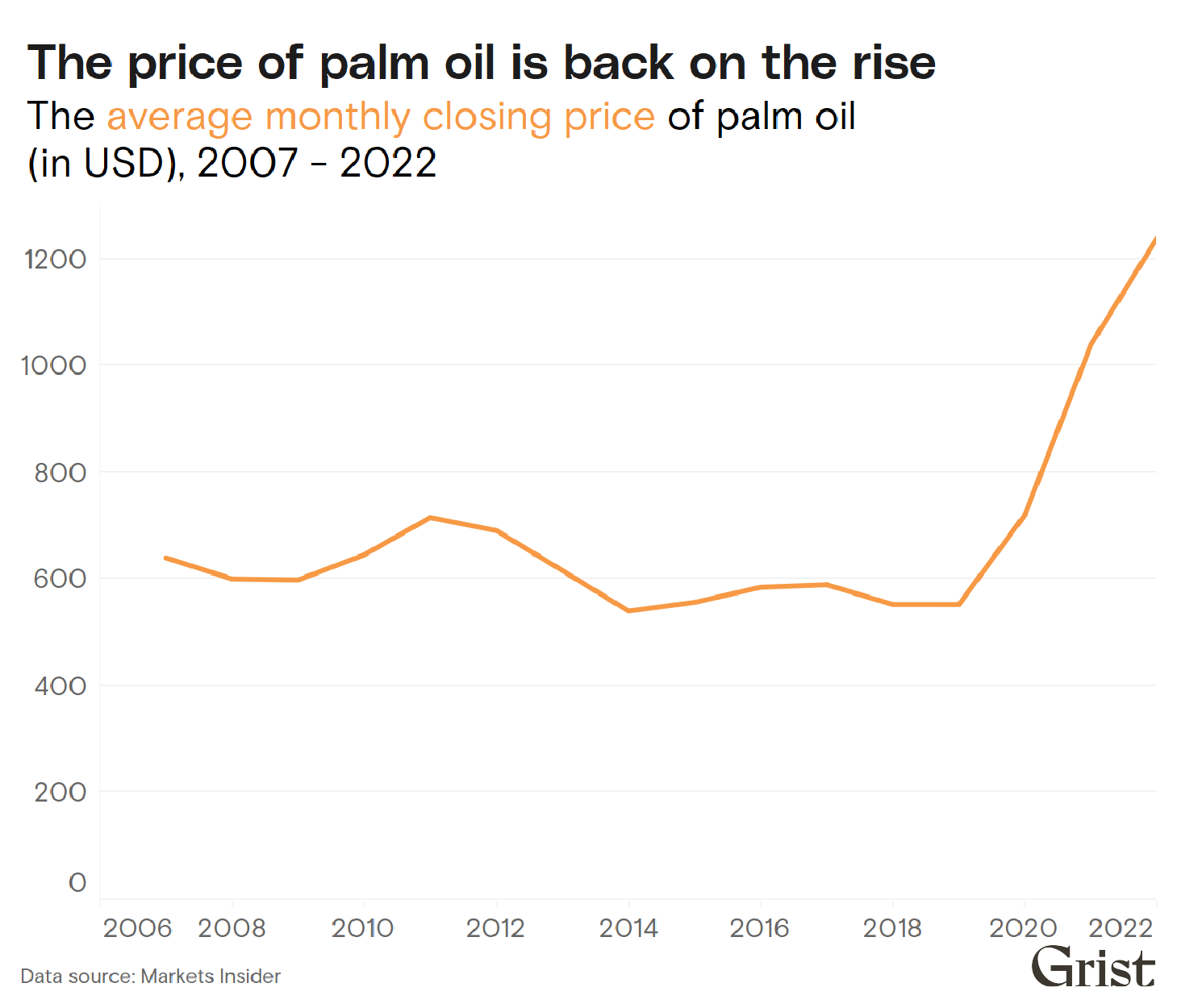

But there is a downside to policy-driven measures to fight deforestation: Should a country’s economic or political situation change, those protections are likely to be watered down or even reversed. One factor in Indonesia’s successful tree protection efforts, for example, has been the relatively low price of palm oil over the last few years. Should the value of palm oil rise in the future, it’s possible that Indonesia’s tropical forest protections could be overturned.

“Palm oil prices started ticking up in mid-2020, and there tends to be a year lag between when palm oil prices start going up and when deforestation linked to palm oil starts to go up,” Goldman said.

In October, Indonesian President Joko Widodo halted the temporary freeze on new palm oil plantation permits that was enacted in 2018. The possibility of a wave of new palm oil plantations coupled with a COVID-19 starved economy could jeopardize what has otherwise been a tropical preservation success story.