As fires ripped through the West this month, displacing families and releasing a thick, choking cloud of smoke that reached all the way to Europe, some scientists began to worry about yet another loss. Thousands of acres of forest, maintained to offset greenhouse gas emissions, might be going up in smoke.

Claudia Herbert, a PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley, who is studying risks to forest carbon offsets, noticed that the Lionshead Fire — which tore through 190,000 acres of forest in Central Oregon and forced a terrifying evacuation of the nearby town of Detroit — appeared to have almost completely engulfed the largest forest dedicated to sequestering carbon dioxide in the state.

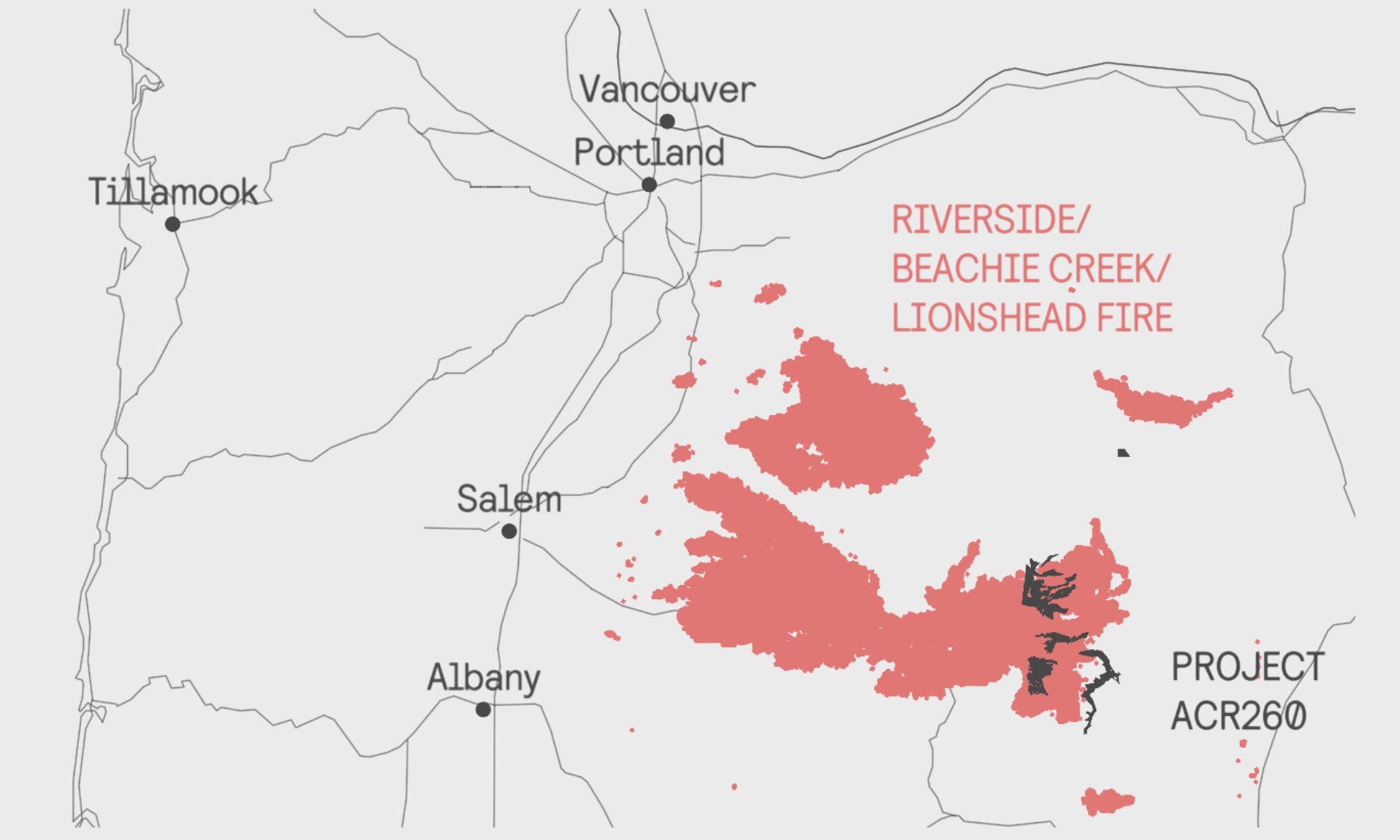

Intersection between the Riverside/Beachie Creek/Lionshead fire and the Warm Springs forest offset project (ACR260). Courtesy of CarbonPlan.

The project, owned by the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, spans 24,000 acres. Before the fires, the state of California had issued more than 2.6 million offset credits based on the carbon stored in its trees. That translates to 2.6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide — or the equivalent of driving 560,000 cars around for one year.

California has a cap-and-trade law that limits greenhouse gas emissions from major emitters like power plants. Those companies, however, have a little bit of leeway — in order to meet the law’s requirements, instead of fully reducing their emissions, they can buy “carbon offsets.” Those often take the form of paying a forest manager to boost growth so the trees will suck up, and store, more carbon dioxide over the long term: in theory, at least 100 years. Those offsets are supposed to counterbalance any extra emissions, so the climate is no worse off than before.

Runaway wildfires, however, throw a wrench in that plan — and as climate change intensifies fires around the world, forest carbon offsets are only going to get riskier.

“If a forest burns down, you didn’t keep carbon out of the atmosphere,” said Danny Cullenward, an energy economist at Stanford University. “So if you let a refinery pollute more because they bought an offset premised on those trees, you have a problem.”

Luckily, California anticipated this problem. The California Air Resources Board, or CARB, which oversees the offset program, built in a type of insurance that accounts for risks like fire, disease, and drought.

This is how it works: Land owners that manage forests under California’s program only get paid for between 80 and 90 percent of the carbon they store. This means all of the forests in the program are storing an extra 10 to 20 percent more carbon than California actually sells as credits on the offset market. CARB keeps track of this “buffer pool” of extra carbon, and can tap into it if any of the forests with existing credits get destroyed.

For example, back in 2015, a fire wiped out Trinity Timberlands, a forest management project in Northern California worth about 850,000 credits. In response, CARB pulled 850,000 credits out of the buffer pool to compensate for all that lost carbon storage. The system worked.

But right now, the buffer pool has about 25 million credits — and some scientists are worried that won’t be enough. William Anderegg, a researcher at the University of Utah, thinks there’s a strong case that current policies around forest carbon offsets, including California’s, underestimate the risks from climate change. Studies show that fire frequency, size, and severity will continue to get worse due to climate change, especially if the world doesn’t start seriously cutting emissions. Anderegg also pointed out that California’s program assigns the same risk to forest carbon offset projects around the country, even though fire risk in Maine is really different than in California.

The Lionshead fire is still burning, and it’s hard to say how bad the damage to the Warm Springs project will be. In the absolute worst case scenario, however, the damage could be devastating: If all of the 2.6 million tons of stored carbon is unleashed into the atmosphere, that means that as much as 10 percent of the entire buffer pool would be wiped out by just one fire.

“This doesn’t mean we should give up on offsets, but we need to be clear-eyed about this,” Anderegg said. “If we don’t have the risks priced correctly, we’re basically investing in a bunch of climate policy that may turn out to be worthless.”

The possibility of underestimating insurance doesn’t just affect California’s climate goals. Tons of companies voluntarily purchase forest carbon offsets through other markets in order to claim they are reducing their emissions or are “carbon neutral.” Anderegg’s lab group is currently working on calculating the risk of fires, droughts, and insects for forests in different regions of the country, and plans to make that data available for California and other carbon offset programs.

Jason Gray, chief of the cap-and-trade program at CARB, said that after a fire or some other kind of disturbance, a project manager has 30 days to notify the agency. That kickstarts a two-year process to vet the remaining forest and see how many offsets were saved — and how many need to be taken out of the buffer pool. He said that once the agency gathers more information about what happened this fire season, it will inform future amendments to the program, in addition to the latest science and public input.

For Herbert, the PhD student, it’s hard to separate her academic interest in carbon offsets and what happened in Oregon with her personal feelings of grief. “You do this work because you want to inform and make things change,” she said. “But seeing pictures of this happening isn’t necessarily the type of relief or validation you might hope for.”