Alex Wolfe doesn’t hike. He walks for very long distances, which is an important distinction. Rather than toiling along the Appalachian Trail or scrambling over Wyoming rock fields, his routes cover less majestic landscapes: a Long Island turnpike, the banks of New Jersey’s Raritan Canal, the strip malls of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. These suburb-spanning slogs have all been made in an effort to answer the question: What can we learn about our environment when we travel on foot through a place that is not designed to be walked?

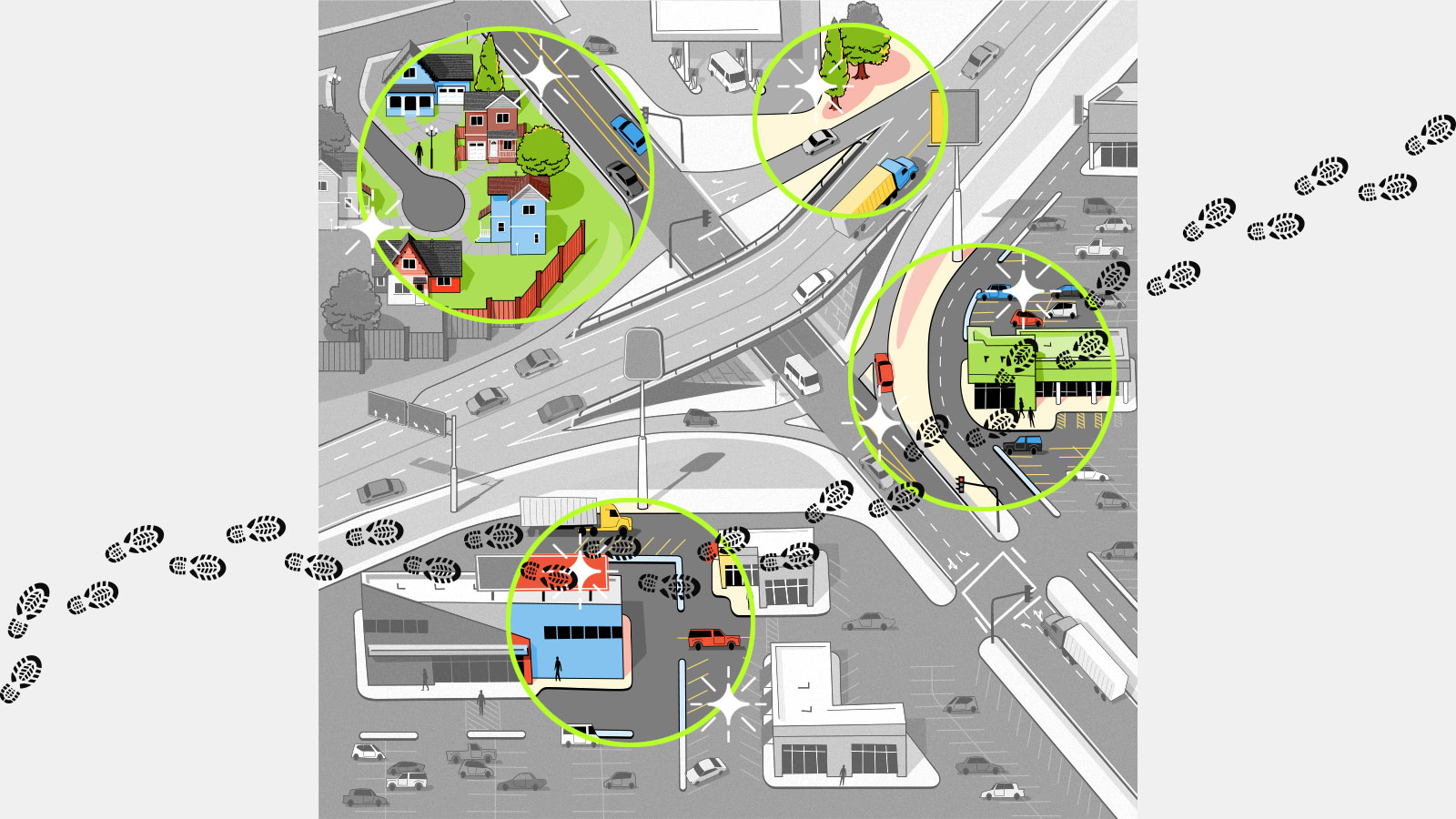

Many of the cities and neighborhoods we ostensibly built for ourselves were actually built for our cars. Anyone who has ever tried to walk to a grocery store in a typical suburban neighborhood, for example, or cross a six-lane arterial to get from a Target to a Best Buy on foot, knows that to be a pedestrian in most of America is to work your way around a lot of obstacles. There are roads with no sidewalks, where you must teeter tightrope-style along a narrow shoulder flanked by 60 mile-per-hour traffic. There are the perilous no-crosswalk blocks where would-be walkers’ safety is left to the mercy of passing motorists. Even in the densest of cities, there is often the perpetual maze of construction sites that force foot travelers from sidewalk to traffic lane.

These are all familiar obstacles to Wolfe. He once walked the length of Western Avenue in Chicago, a major thoroughfare that spans 24 miles. He has traversed the entire isle of Manhattan, north to south, and then some in one go. This year, he completed two multi-day treks of 180 and 160 miles, respectively, traveling from his home in Brooklyn to Philadelphia in May and Montauk in October.

The initial inspiration for Wolfe’s work was “not born out of an eco-friendly, advocacy lens,” he said, but navigating so many roads and thoroughfares on foot made him realize the “subtle kind of stress you carry with you in these spaces” when you’re not traveling at 60 miles per hour ensconced in a few thousand pounds of steel. And the more we depend on cars to safely get us even a mile away from home, the more carbon emissions we’re building into our daily lives. (The electric revolution may be impending, but it is not yet here.)

Many active transportation advocates were hoping for more in the way of pedestrian-friendly city planning as part of the Biden administration’s heavily contended trillion-dollar infrastructure bill that passed last month. And while federal funding opportunities for cities that want to improve pedestrian and bicycle safety did grow, it’s a drop in the bucket compared to how much money has been allotted toward improving and expanding the nation’s already sprawling highways. For all the climate bravado of some politicians, it seems cars are still very much king.

Wolfe is used to bewilderment from followers that he enjoys walking dozens of miles through less-than-picturesque settings like North Jersey and Long Island, the butts of so many jokes about suburban hellscapes. Wolfe maintains the negative perception of those places is largely driven by the fact that many people experience them primarily from behind a windshield. “I think you get such a limited scope of what these places are [while driving],” he said. “I get a lot of joy out of figuring out why these places are terrible, and more often than not they’re not terrible at all.”

Wolfe meticulously documents his walks in photos and writing that he shares on Instagram and via newsletter. He says that part is important, too; capturing his journey is an artistic practice through which he tries to highlight the characters of places overlooked by drivers.

“I have just such a deep desire to connect with my surroundings, and I found that walking is the most intimate way to experience your surroundings for better or for worse,” Wolfe explained. “There’s a beautiful thing of watching your surroundings unfold in front of you. Going from Queens to Montauk and watching that subtle progression of strip malls and parking lots to nature to the ocean — it’s so powerful.”

I became fascinated by Wolfe’s work because I used to walk places, and then I didn’t. As a teenager too unmotivated to get a driver’s license, I would routinely cover two or three miles across Pittsburgh in the middle of the night to come home from parties, the stupidity of youth blissfully insulating me from the reality checks of danger and cold. When I moved to Chicago a few years later, delayed buses or overcrowded trains would often make a journey on foot seem an almost pleasant alternative, even under the most ghastly lake effect conditions. In Seattle, the unceremonious death of my car’s transmission meant that walking became simply necessary.

But somewhere along the line, something shifted for me about which places I saw as worth walking. I got more into the outdoors, which meant driving several hours round trip to go for a walk. The urban treks that had been part of my every day seemed to pale in comparison – both in exertion and scenery – to the spectacular hikes of the Pacific Northwest. Towering old-growth forests and alpine mountainscapes offered something very different from the artificial valleys of downtown skyscraper-lined streets or long Midwestern blocks of gas stations and big box stores.

It seems to be a cultural stance of the American white-collar class that if you are going to go for a long walk, you ought to be doing it in the wilderness, or as close to it as possible. Spending time in nature has important physical and mental benefits, to be sure, to say nothing of the appreciation it instills for the beauty and preciousness of natural ecosystems. But the realities of contemporary life mean that very few of us can be out in the woods and mountains and streams all of the time. It requires, at minimum, free time, a car, a decent amount of disposable income to spend on the necessary and very expensive gear.

The more I got into hiking my idea of “outside” somehow developed, like so many other aspects of American life, along a new valuation spectrum of my own making. Nature was better for walking, cities were worse. And in my daily life, I found myself increasingly reaching for my car keys. Since I still spent almost all of my time in cities, the net result was that I was more confined to the indoors.

As Wolfe’s work seeks to remind us, our cultural purity test for outdoorsiness and reluctance to walk in urban settings represents a real loss. Much has been written by better writers than I about how walking can be the best way to get to know both a city and oneself. The bulk of the action of the novel Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf is built around the main character walking around London and reflecting on her life. She observes all the delightful and mundane details of life on the street (very Jane Jacobs), runs into old friends and lovers, rhapsodizes over the budding beauty of England on a June morning. “I love walking in London,” she declares. “Really it’s better than walking in the country.”

Similarly, New York-based writer Cat Marnell has penned many an ode to the calming and grounding effects of a middle-of-the-night miles-long walk around a new or familiar neighborhood. In earlier columns, she’d describe how Manhattan streets at 4 a.m. brought much-needed quiet to her drug-addled brain. Her audiobook on her European travels made a case, safety concerns notwithstanding, for nighttime explorations of foreign cities; sidewalks were free of tourists and full of enchantment. “It would just give me this magic in my brain that was like peace for me,” she told Audible.com in an interview.

But in my opinion, the story that best captures the bleakness of a world in which walking is increasingly rare is Ray Bradbury’s short story “The Pedestrian.” This piece of science fiction is set in 2051 (a date 100 years in the future at the time it was published), and technological advances have allowed society to go nearly 100 percent virtual, removing people’s need to venture outside of their homes. And yet, the main character, Leonard Mead, strolls his silent neighborhood at night, watching his neighbors inside with their televisions. That is, until he gets stopped by the police, who demand a reason for why he chooses to go walking. He replies: “For air, and to see, and just to walk.” In response, the authorities take him to a psychiatric research facility.

If this sounds uncomfortably familiar, well, welcome to 2021. When the COVID-19 pandemic started and the whole world was driven into their homes, people became more eager to walk around their neighborhoods so as not to be driven insane by shelter-in-place claustrophobia. Nearly two years later, many of us are still quite housebound, but those nearby circuits are well-worn and not offering much in the way of mental refreshment.

When every encounter with a stranger entails some degree of risk calculation, being outside can be exhausting. And the less we are outside, the more we lose connections that ground us to our communities and our environment.

Wolfe shared that when he takes on these long-distance walks, most people that he meets along the road react with “almost universal fascination” to this undertaking that is, at its heart, incredibly basic: just walking. Because in so many places, it is so unusual to see a pedestrian.

Granted, a place built for cars means that it comes with safety issues for those who just want to ambulate along it on their own two legs. (Wolfe has never been hit by a car, but confessed that at the end of a long walking day he has found himself crying from the cumulative stress of busy roads and the “violence” of traffic.) Some cities, in an ostensibly well-meaning effort to make walking safer for all, have increased enforcement of jaywalking fines – which just ends up punishing pedestrians and burdening the poor.

But it does seem too bleak a fate to simply accept the place you live, no matter how unremarkable by travel guide standards, as somewhere you cannot just go outside. Perhaps the best way to counter that is simply to walk, as much as you are able to do so. Nothing changes if no one wants it to change; no one wants something to change unless they recognize why it’s wrong. This is the same idea that you’ll hear bicycle advocates invoke when they talk about what’s needed to create more bike-friendly cities. You don’t know how badly better infrastructure is needed until you try to get around on two wheels – or two feet, as the case may be – yourself.