On Saturday, as protests demanding racial justice and an end to police violence took over New York City, a separate but related demonstration wound its way through Brooklyn echoing those cries and adding a few more. This other protest took place on bikes, as a few dozen New Yorkers rode the route of a partially constructed natural gas pipeline. As they pedaled through neighborhoods between Brownsville and Greenpoint, the cyclists drew attention to the disproportionate burden of environmental hazards in the predominantly black and brown communities that live along the pipeline’s path, calling on state regulators to put an end to the project.

Formally called the Metropolitan Reliability Infrastructure project (MRI), the 7-mile-long, 30-inch-wide pipe is technically a “transmission main.” Unlike the Williams Pipeline, which would have delivered fracked gas to New York City from Pennsylvania but was recently struck down by the state, the MRI is a much smaller project that will not bring a new supply of gas into the city. National Grid, which is building it, says its primary purpose is to increase the “safety, reliability, and operational flexibility” of the system. The MRI essentially provides “another lane” for the company to deliver gas to customers, according to company spokesperson Karen Young. However, even though the project won’t directly bring new gas into the system, the company has said that it needs the MRI to handle additional gas from other proposed projects, like the expansion of its liquefied natural gas facility in Greenpoint.

Construction of the Metropolitan Reliability Infrastructure project underway on Moore Street in Brooklyn. Erik McGregor / LightRocket via Getty Images

Construction of the MRI started in 2017, and the first three “phases” have already been completed in Brownsville and parts of Bushwick. Construction on phase 4, which extends through East Williamsburg, started in the fall. But the company does not yet have approval to complete phase 5 — the home stretch through Greenpoint to National Grid’s liquefied natural gas facility on Newtown Creek. The company is currently in the process of asking state regulators to hike up customers’ gas rates to raise the $185 million needed to complete it.

The bike ride on Saturday was organized by the No North Brooklyn Pipeline campaign, a coalition of community organizations and environmental groups that joined forces to try to shut the project down after they learned about it last fall. Throughout the protest, speakers explained that they had no idea a gas pipeline was going to be built in their neighborhood until construction crews showed up. They oppose the project for a number of reasons, including the cost to ratepayers and the climate risks of building new gas infrastructure, but one of the key issues raised on Saturday was a lack of transparency with impacted communities who they say were not adequately informed or consulted before the company broke ground.

National Grid told Grist that it has an extensive community outreach program including a regularly updated website with construction timelines. Young said the company notifies local leaders, schools, medical facilities, and businesses about upcoming construction in their area and conducts door-to-door outreach to hundreds of residents about two weeks in advance of when crews will be working on their block.

Brownsville native and community board member Gabriel Jamison speaks to a crowd about high rates of asthma and a lack of access to healthy food in his neighborhood. Erik McGregor

For the protestors, though, the MRI isn’t just a pipeline — it’s one more line item on a long list of social and environmental burdens. At the first stop on the ride, Brownsville native Gabriel Jamison spoke to the crowd about high rates of asthma in his neighborhood, and the need for investments in the community to improve access to healthy food and housing options. In Bushwick, protester Noel Sanchez pointed out that communities in the North Brooklyn neighborhoods the pipeline cuts through are already facing gentrification, a racist criminal justice system, and a poor education system. “The last thing we need is this pipeline,” he said.

Third-generation Bushwick resident Jorge Arteaga decried how the pipeline’s route cuts through black and brown, low-income communities. Bushwick residents already suffer from poor air quality due to a waste transfer station, cement plants, and other industrial activity in the neighborhood that brings heavy truck traffic there. “Now more than ever, this is a time for us to use our voices, not just to make a rah-rah, but to see it through and make real structural changes,” Arteaga said.

“Now more than ever this is a time for us to use our voices,” Bushwick resident Jorge Arteaga tells protesters. Erik McGregor

At the final stop of the ride in Greenpoint, Kevin LaCherra, whose family has lived in the area since the late 19th century, spoke about pollution from vehicles on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, an elevated highway. He also recounted the legacy of contamination in the soil and water from old fossil fuel plants along Newtown Creek, including the largest underground oil spill in U.S. history. Newtown Creek is also home to a Superfund site that National Grid inherited partial responsibility for cleaning up when it took over the property.

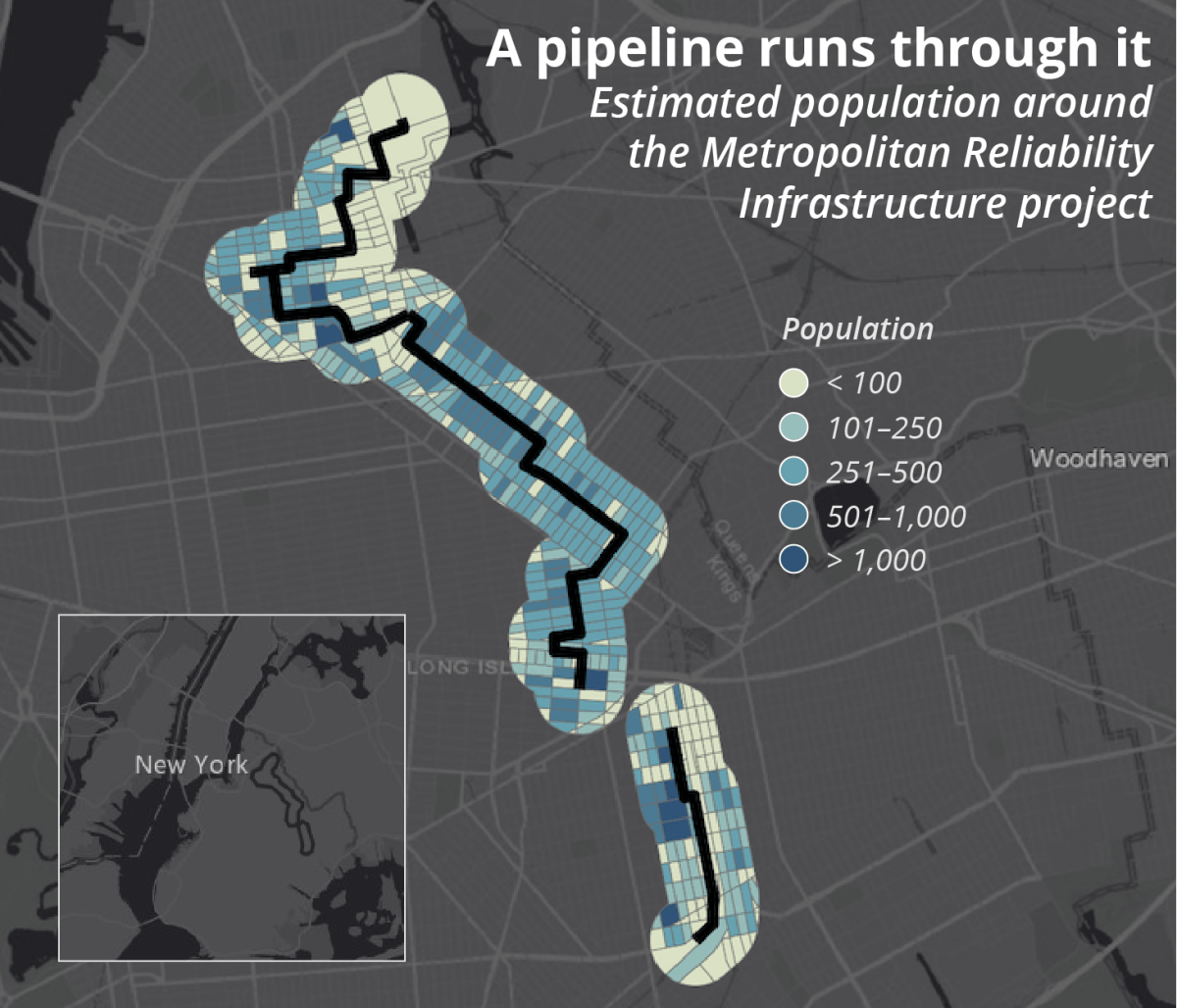

The No North Brooklyn Pipeline Coalition is concerned that on top of these existing threats, folks who live along the MRI’s route will be at risk of explosions or leaked methane. Nearly 153,000 people live within a 1,275-foot radius of the project, in addition to more than 60 schools and 80 daycare centers, according to an analysis by the Fractracker Alliance. In response to that concern, Young of National Grid said that “the gas main project design, engineering controls, and safety features we have in place meet or exceed NYC construction standards and stringent safety guidelines.” At a public meeting in January, engineers from National Grid said pressure in the pipeline was low, and that if there was a rupture, it would leak, not explode.

Whatever the physical risks of the project, it will have a cost burden on ratepayers, particularly the low-income customers who live near the MRI. National Grid originally asked state regulators for permission to raise rates by about 11.99 percent for customers in Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Queens. Richard Berkeley, executive director of the Public Utility Law Project, a nonprofit that advocates on behalf of low-income consumers, told Grist that the double-digit increase would be unaffordable for millions of customers. “Even before the economic collapse from the pandemic, we were extremely concerned about the huge rate increase the company was looking for,” he said. “This is the greatest loss of jobs in New York since the Great Depression, how do they expect people to pay?”

FracTracker Alliance / U.S. Census (2010) / Grist

Investor-owned utilities like National Grid aren’t allowed to make any money on the gas they sell to customers — they have to sell it at cost. But they are allowed to earn a return on their investments in new infrastructure, and that return is built into customers’ rates. State regulators are tasked with making sure companies don’t take advantage of that arrangement and only build things that are necessary for them to fulfill their duty of serving the demand for gas.

National Grid’s rate case — its formal negotiations with regulators over how much to raise rates and what it can spend the money on — is ongoing, so the proposed rate increase could still come down. The increase won’t only cover the MRI and the expansion of the Greenpoint facility: It will also pay for things like routine maintenance, replacing leak-prone pipe, improved methane detection, energy efficiency programs, and investments in low-carbon solutions like renewable natural gas and geothermal heating.

Pipeline sections stored on the street outside of a public housing project in Bushwick. Erik McGregor / LightRocket via Getty Images

The company also claims that federal, state, and local regulatory requirements account for more than 60 percent of its proposed capital expenditures, and that rising property taxes, environmental remediation (like cleanup of the Superfund site), and other operating costs were driving the companies’ rate increase request.

The Sane Energy Project, a grassroots anti-fracked gas group that is part of the No North Brooklyn Pipeline Coalition and has testified in the rate case, argues that if New York is serious about mitigating climate change, regulators should not allow National Grid to build any new infrastructure that prolongs the use of natural gas. The group says the company should instead address gas supply constraints solely through programs that reduce demand, like efficiency upgrades and incentives for customers to switch to electric heat pumps. Both New York City and state passed landmark laws last year that seek to drastically reduce carbon emissions by 2050. The city’s Climate Mobilization Act specifically aims to cut emissions from buildings — the majority of which come from natural gas heating systems. Critics say building new projects like the MRI will hook New Yorkers on gas for decades to come, making these goals harder to accomplish.

This perspective is shared by New York City comptroller Scott Stringer, and elected officials like Senator Julia Salazar and Assembly Member Joseph Lentol, who have all sided with protesters against the MRI. “I have called for a moratorium on major gas infrastructure because we know the infrastructure we install today only puts our climate goals further out of reach,” Stringer said in a statement.

The communities along the MRI are also more vulnerable to the climate effects of New York City’s continued reliance on natural gas. These neighborhoods are already highly vulnerable to heat in the summer, and their residents are less likely to be able to afford adequate air conditioning.

“Being communities of color, we will be hit first and worst by climate change. We’re already feeling the effects so we are extremely alarmed by this,” Leslie Velasquez of the Williamsburg-based community organization El Puente said in a statement.

Climate change isn’t the only long-term risk. The high price tag of new gas infrastructure like the MRI will not only burden consumers now — that burden could grow in the future. As climate policies push New Yorkers to switch to electric stoves and heating systems, the gas ratepayer pool will grow smaller, and fewer customers could be left footing the bill. Unless the state plans for an equitable transition, those remaining ratepayers are likely to be low-income residents who cannot afford electric upgrades.

Saturday’s protest ended outside of National Grid’s liquefied natural gas facility in Greenpoint. Erik McGregor

These questions about how new gas infrastructure fits into New York’s climate goals and about the risks of not planning ahead for an equitable transition have been raised by environmental groups like the Environmental Defense Fund and the Pace Energy and Climate Center in rate cases for several years now. So far, the state’s Public Service Commission (PSC), which regulates utilities, has not tried to answer them. But in March the commission announced it was opening a new proceeding to make natural gas planning in the state more transparent and better aligned with the state’s climate targets, recognizing the shortcomings of the existing process to address these issues.

For the No North Brooklyn Pipeline Coalition, the best-case scenario would be for the Public Service Commission to reject National Grid’s request to charge ratepayers for the MRI in the current rate case. The case has been delayed by complications from the COVID-19 pandemic, and new rates will likely not go into effect until November.

“We’re demanding that the PSC listen to city and state climate law and the thousands of public comments from the community and reject the MRI pipeline and do it now,” said Lee Ziesche of the Sane Energy Project. Ziesche worries that if the PSC doesn’t make a decision soon, National Grid will continue construction until the decision is effectively moot. “They can’t let National Grid build this pipeline without approval for funding, against the will of the community, and wait until construction is completed in the fall to make a decision.”

So what would National Grid do if regulators reject the MRI? “National Grid is committed to making the system upgrades necessary to maintain safe and reliable service for our customers,” Young told Grist. “The project costs will be addressed through the rate proceeding process before the Commission.”