Hurricane Ida, one of the strongest storms to hit the U.S. on record, intensified so rapidly before hitting New Orleans that city officials did not have enough time to issue a mandatory evacuation order. Limited exit routes from the city meant that people would have been stuck in traffic on the highway when the storm came. Those who stayed in the city and surrounding area were hit by 150-mile-per-hour winds and heavy rains that knocked out power to almost 1 million homes and businesses in Louisiana and Mississippi on Monday. By Thursday afternoon, in the midst of the blazing heat wave, Entergy, the utility that serves most of the region, reported that only 18 percent of its system had been restored.

At the same time that stronger, wetter storms like Ida are exposing the dangerous weaknesses of the U.S. electricity grid, the clearest pathways to stop the effects of climate change from getting worse all involve people becoming more and more reliant on it — for example, by trading gas-powered cars for electric ones, or using renewable electricity to heat homes. As demand for electricity grows, experts say that the way utilities and policymakers address grid resilience, which is largely reactive rather than preventative, has to change.

“The reality is, our infrastructure is built for the climate of the past, and we keep rebuilding it by incremental improvements,” said Roshi Nateghi, an assistant professor of industrial engineering at Purdue University. “And that’s just not gonna cut it.”

Resilience is a slippery word. There’s no universally agreed-upon way to define or measure it. Experts say it’s unrealistic to expect a grid that never has outages, but there are at least three different kinds of solutions that Nateghi and others point to that could help our electricity system withstand stronger storms and, in the inevitable case of an outage, ensure that communities get the minimal service needed to remain safe.

The first begins with what we’ll call the old, incremental way of thinking — a focus on the physical infrastructure that makes up the grid. The scale of the damage wrought by Ida was severe. Entergy reported that within its transmission system — the high-voltage poles and wires that deliver electricity from power plants to the distribution lines that serve customers’ neighborhoods — more than 200 wires and 200 substations had been put out of service by the storm. In its distribution system, about 10,000 poles, 13,000 wires, and 2,000 transformers were damaged or destroyed.

There’s a lot utilities can do to minimize this kind of damage during storms. They can design systems to withstand stronger winds by using stronger wires supported by poles spaced more closely together. They can replace wooden poles with concrete and steel, and be diligent about trimming trees nearby. But Nateghi said these kinds of fixes are piecemeal and may be more expensive in the long term than an often-debated solution with high upfront costs — burying power lines underground. “It’s always argued to be really expensive,” said Nateghi, who said that when you look at the full costs of these disasters, many of which enter the billions, it might not seem as expensive. Buried lines are protected from wind and can be insulated from flooding. The downside is that they are harder to access for repairs.

Logan Burke, the executive director of New Orleans-based nonprofit the Alliance for Affordable Energy, said there have been conversations about burying lines in New Orleans for decades. Part of the problem is that the cost of burying lines would likely get passed on to customers through their electric bills, and that the city, and Louisiana at large, has extreme levels of poverty and high energy burdens. Half of the low-income households in New Orleans spend more than 10 percent of their income on energy, according to a 2016 report, and a quarter spend more than 19 percent, compared to a national average energy burden of 3.5 percent.

“The hesitance to burying lines is, how do we do this in a way that people can afford?” said Burke. Unless the federal infrastructure bill, or a reconciliation bill, provides additional dollars for that kind of project, she said, it’s simply not an option for Louisiana.

The bipartisan infrastructure bill that the Senate passed in early August contained $65 billion for the power grid, with $10 billion to $12 billion specifically for building new transmission lines. The Biden administration also announced last month that it is making nearly $5 billion available through the Federal Emergency Management Agency for projects that improve community resilience to extreme weather.

The second possible solution, which is cheaper than burying lines and something that utilities can take advantage of today, is using predictive computer modeling to identify where the biggest weaknesses in their systems are in order to make those incremental improvements more strategically. Nateghi and other academic researchers have published methods that use meteorological models of climate impacts and translate them into potential infrastructure damage to predict which areas are most likely to lose power. As part of her doctoral research, Nateghi worked with utilities in the southeast to incorporate such models into their planning and said they were able to cut costs and fare better in future storms. Farzad Ferdowsi, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Louisiana who has worked with Entergy, agreed that one of the things the company could do to improve resilience is more comprehensive modeling.

But regardless, the grid will sometimes fail in one way or another. That’s why Burke thinks it’s more important to shift the conversation around resilience away from utilities to people. “We think it’s so important to be thinking about how to help people stay safe in their homes or where they’re sheltering, and that includes things like distributed solar and storage,” she said. New Orleans has a lot of rooftop solar, but most of it isn’t paired with batteries, which would allow it to provide power when the larger grid goes down. Burke imagines homes and community-based organizations like libraries, churches, and schools that have solar and storage systems that could be connected to form “neighborhood reliability corridors.” They would be able to operate as microgrids, independently from Entergy’s system, and allow communities to access cooling and other basic electricity needs in the aftermath of storms.

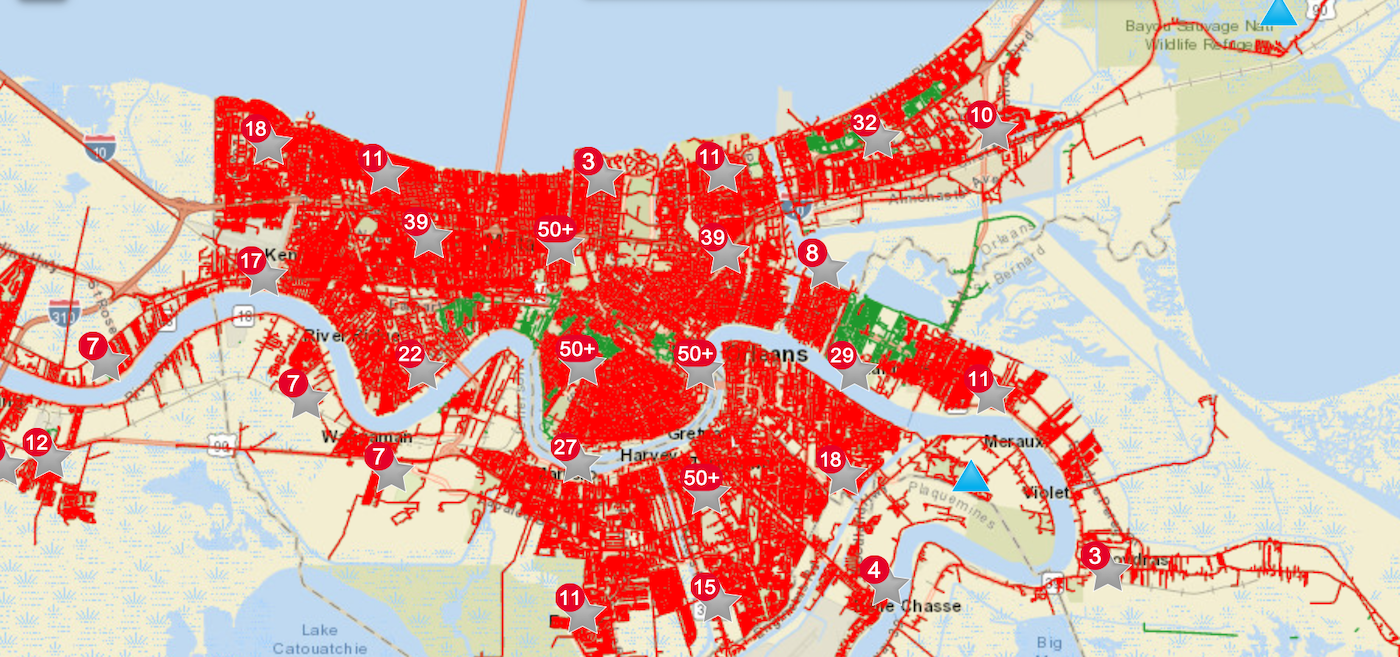

Entergy has forcefully fought proposals to allow for more locally produced and controlled electricity in New Orleans, instead convincing the city council to allow it to build a new gas-fired power plant in the city on the grounds of improved resilience during storms. That plant didn’t keep the power on during Ida because of damage to transmission and distribution lines. The company was able to start it up on Wednesday morning and provide power to a small part of New Orleans East, but most of the city is still blacked out, and Entergy has not yet provided estimates for when power will be restored.

“We expect to complete assessing all damage today, and then we can begin providing estimated restoration times for customers,” said Deanna Rodriguez, Entergy New Orleans’ president and CEO, during a press conference on Thursday morning.

Entergy can earn a rate of return on big capital investments like power plants, while locally produced solar would eat away at its profits. Like in other cities, Burke said that in the last month she has heard lots of calls for a public power utility that wouldn’t be subject to profit-motivated decision making. But she’s not very optimistic about a future for public power in New Orleans.

“New Orleans only has one Fortune 500 company, and it is Entergy,” she said. “They wield political power, they fund a lot of nonprofits. The kind of power that they have is fairly unmatched in the state. And so a movement to municipalize has a big heavy barrier up against it.”