In June, state security forces in the United Republic of Tanzania engaged in a violent eviction campaign against Indigenous Maasai, shooting them and driving them from their lands. The attack took place in Loliondo in northern Tanzania near the Kenyan border. Dozens of Maasai were injured, some fleeing to Kenya to seek medical attention, while others were arrested.

The violence was the Tanzanian government’s latest move in a years-long campaign to remove the Maasai and make way for game reserves, protected areas, and tourism. Amid months of increasing state violence and persecution, Maasai leaders have called for urgent international attention and intervention.

So when Salangat Mako, a Maasai leader, heard that the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights was going to make a monitoring visit to Tanzania, he felt like his prayers had finally been answered. Mako was chosen alongside five other community members to speak to the Commission on their planned visit to Loliondo.

Throughout the day, Mako and other community members rehearsed their statements, skipping lunch, and growing excited every time they heard a car approach. But late in the afternoon, they received news that the Commission was not coming to Loliondo. “The little hope that was ignited in the morning vanished in a second, replaced by desperation and hopelessness,” Mako said.

Angry and disappointed, Mako wanted to find another way to get his message out. Samwel Nangiria, another Maasai leader, decided to film a video of Mako.

“I have become a thief in my own land,” Mako said in the video. “A community depending on livestock, without grazing land. Where is our future? Where is our tomorrow? Where will our children be?”

Nangiria and Mako sent the video to the Commission and other activists. Some posted the video on social media, hoping that the Commission and the world would pay attention. Instead, government officials came to Loliondo the next day, and announced that they planned to arrest Mako and whoever filmed and shared the video. Mako has since fled to Kenya. Nangiria is in hiding.

The Maasai say the violence and persecution they face are the result of domestic and international conservation policies — a years-long effort by the Tanzanian government to destroy Indigenous ways of life, and drive tens of thousands of Maasai off their land to establish game reserves, reach global conservation goals, and support tourism.

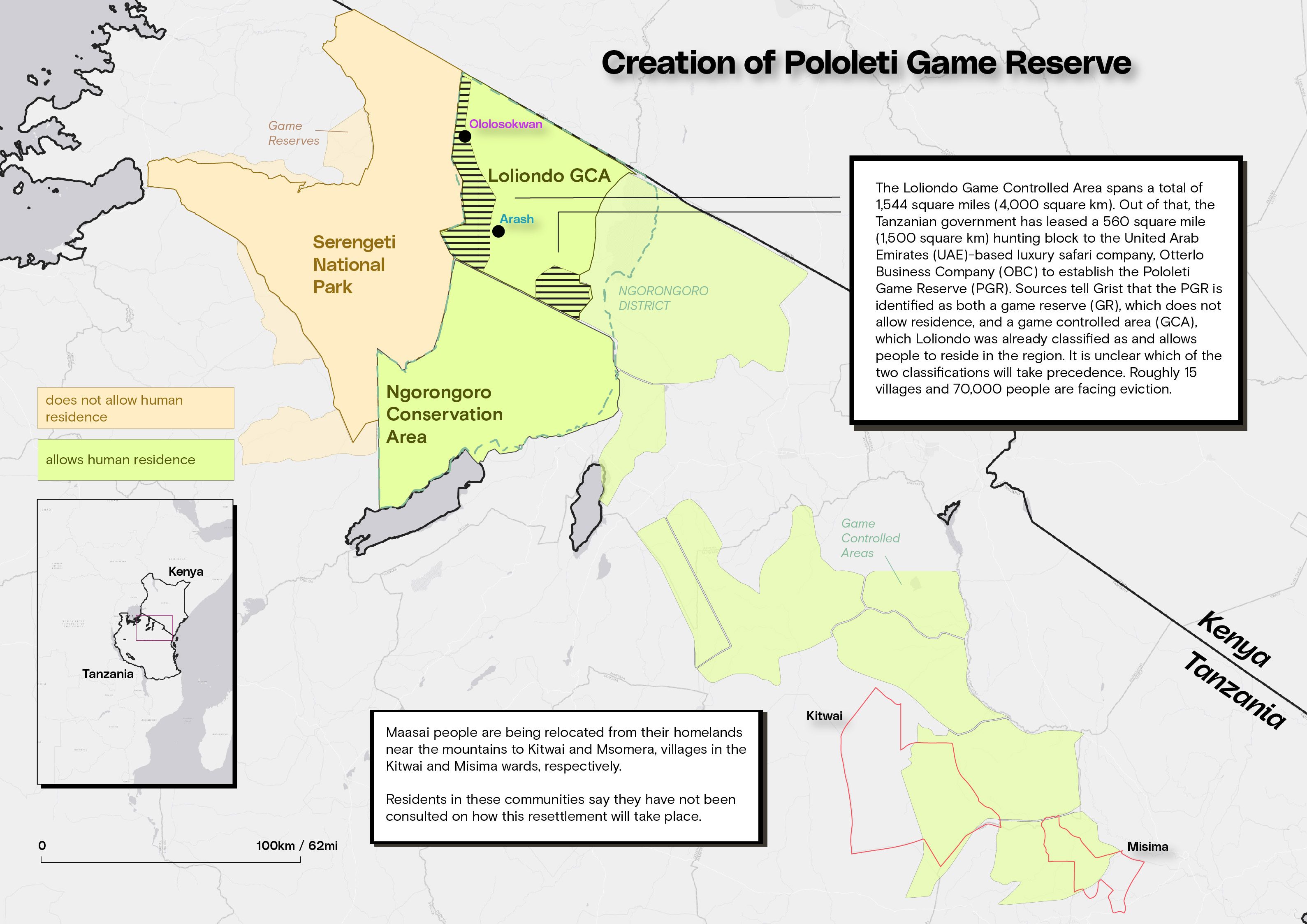

When Tanzania created Serengeti National Park in the mid-20th century, Maasai pastoralists living there were forced to relocate. Many moved to the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, a mixed-use piece of land to the east that is home to about 70,000 Maasai. The Ngorongoro Conservation Area is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the country’s largest tourist attraction, drawing over half a million visitors each year.

In 2019, the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) urged Tanzania to develop a plan to limit population growth in the park, saying it was a threat to conservation efforts and the “value” of the park. The Tanzanian government responded by cutting access to services and resources for Maasai in an attempt to force them out of the area. Although many Maasai have remained in the park, they face increasing pressure to make way for international tourists who pay thousands of dollars for safaris.

In a statement, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee said, “Neither the World Heritage Committee – the intergovernmental body of 21 elected States governing the Convention – nor UNESCO Secretariat have at any time asked for the displacement of the Maasai people.” The World Heritage Committee added that it is concerned about conflicts in the area and has recommended that Tanzania invite an advisory mission led by the World Heritage Centre, but Tanzania has not responded to the request. The statement echoes a March 2022 communique that also said it is ready to help the government develop a sustainable solution.

Many Maasai who were evicted from the Serengeti also relocated to Loliondo, a district north of Ngorongoro on the Kenyan border, where they have legally protected village land. But in 1992, the Tanzanian government granted a hunting block in Loliondo, the Pololeti Game Reserve, to a United Arab Emirates-based luxury safari company. Since then, the Maasai say the government has repeatedly attempted to force them from their land. In June of 2022, the violent attack by state security forces left dozens of people injured and arrested – prompting Salangat Mako and other Maasai leaders to request international observers and support.

At the time, the African Commission publicly called for a halt to evictions: “The African Commission is gravely concerned that the forcibly [sic] uprooting of the affected communities entails grave danger to various rights of the members of the communities.”

The Maasai say the most recent visit from Africa’s highest human rights protection body is a government-controlled sham, and the Commission’s visit comes on the heels of a scuttled United Nations trip. In December of 2022, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, José Francisco Calí Tzay, was scheduled for a week-long visit to Tanzania. Days before Calí Tzay was scheduled to arrive, the Maasai say the visit was postponed out of fear that the government would not allow an independent investigation. The Special Rapporteur had no comment on the matter and would neither confirm nor deny the reason for the trip’s cancellation.

The Maasai are now calling for a new, independent visit by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, or any international observer for that matter, to investigate the decades-long campaign to remove the Maasai from their homelands. They’re not optimistic. “Our government can control anyone who is coming to our rescue,” Nangiria said.

Based in the Republic of The Gambia, the African Commission was established by an international human rights agreement that over 50 African countries, including Tanzania, have adopted. The Commission, however, does not have enforcement power and cannot compel countries to accept its recommendations.

In a draft communique from the Commission’s visit obtained by Grist, the Commission’s observers express concerns about the government’s relationship and treatment of Maasai people, but generally applaud the government for “providing ample access to the agro-pastoral communities,” and highlights that the Maasai enjoy more complete recognition of their rights under the Tanzanian government as opposed to previous colonial government administered by the British.

But Samwel Nangiria believes the system persecuting Maasai has not changed. “The colonial government initiated it and the independent government inherited and carried it forward,” he said.

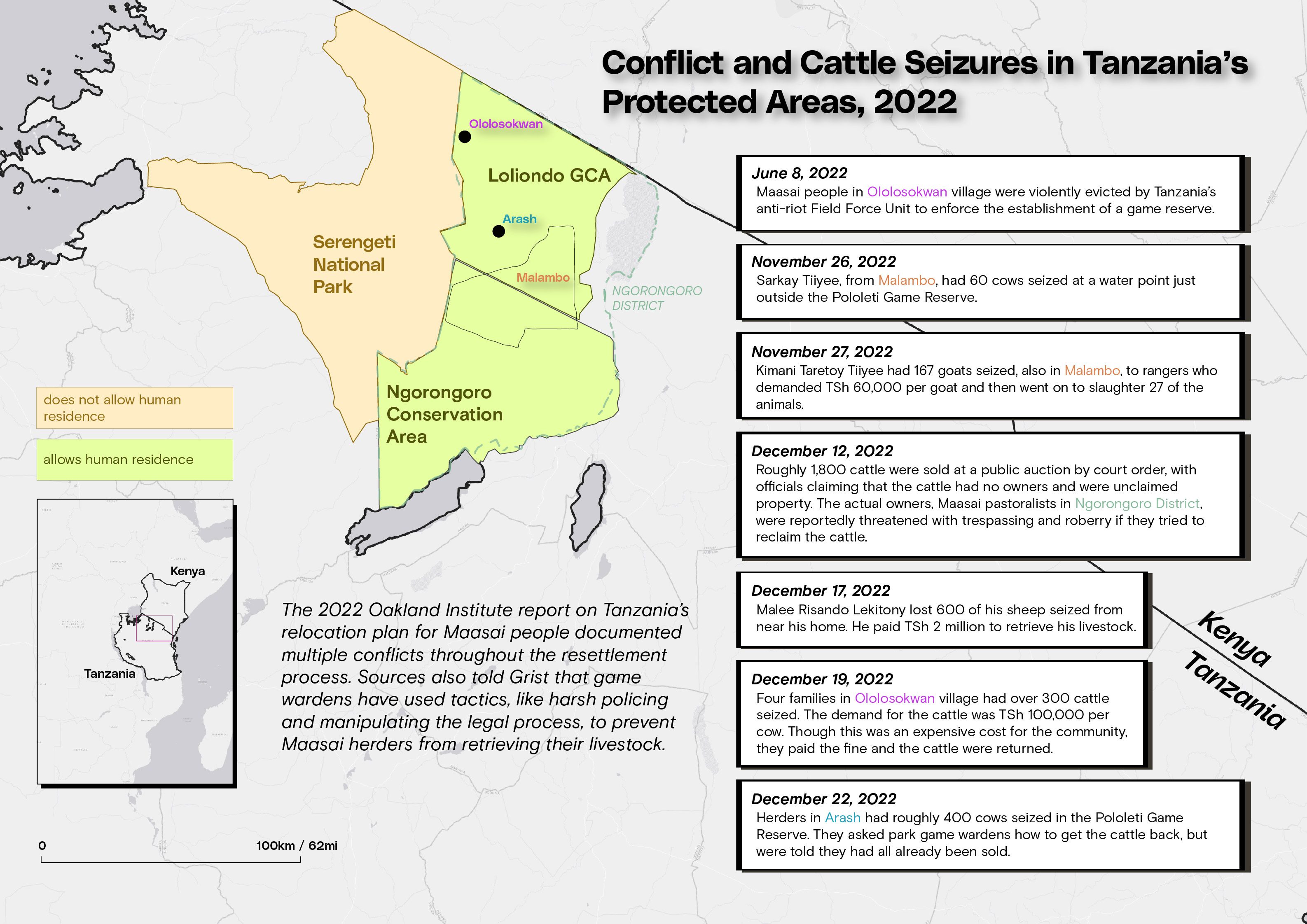

The latest attacks on the Maasai have come in the form of cattle seizures by state security forces. Since June, the government has seized or shot over 10,000 Maasai cows and collected over $2.5 million in fines. “Every corner that the Maasai pastoralists are there, the government is seizing livestock in a manner never seen before,” said Joseph Oleshangay, a lawyer representing Maasai in several cases against the government.

The Tanzanian government says that Maasai pastoralism is detrimental to conservation efforts inside the UNESCO site, but research shows maintaining pasture lands is good for biodiversity in Ngorongoro. Growing research, including from the IUCN, reveals that the protection of grazing land is one of the most important adaptive strategies for climate change.

“The driving force for our elimination is colonial conservation, a conservation that knows only the guns, military and money,” Nangiria said. “The colonial governments and their allies, particularly wildlife lobby groups, are still extending serious influences on how conservation is carried out in Africa.”

Mathew Bukhi Mabele, a conservation social scientist at the University of Dodoma in central Tanzania, says that if the government truly cared about conservation, they would focus on reducing invasive species and limiting tourism, both of which contribute to biodiversity issues in Ngorongoro. “The thing about revenue generation is they don’t think about the consequences of having such a large number of tourists per day,” he said.

Neither representatives from the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights nor the Tanzanian government responded to requests for comment on this story.

Maasai allege that at every step, the Commission was accompanied by state security forces who intimidated Maasai people, excluded them from meetings, and threatened those who spoke up about ongoing human rights abuses.

Maasai lawyer Joseph Oleshangay says that the government prevented the Commission from visiting Maasai in Loliondo while residents of Msomera, a village many Maasai are being relocated to, also say they were prevented from participating in meetings with the Commission. Oleshangay also alleges that Commission members traveled with officials that have been accused of directing violent evictions, further preventing victims from interacting with human rights observers.

“How on earth can you ride in those vehicles?” Oleshangay said. “We feel like they are being used by the government to justify that nothing happened.”

During the visit, nine community organizations wrote multiple letters directly to the Commission. “The state party succeeded to divert the Commission from meeting indigenous peoples independently without the presence of government machinery as agreed and planned for,” reads one communication. “Hence rendering the Commission powerless to collect, analyze and consequently objectively report on human rights situation in those sites.”

In response, the Commission offered to conduct additional meetings with Maasai via Zoom, however, Oleshangay says the offer is the equivalent of being denied a consultation. “To many of the Maasai on the ground, internet is not available,” Oleshangay said.

Tanzania’s treatment of Maasai has come under increasing scrutiny from international observers. Over the last ten years, United Nations Special Rapporteurs have issued seven communications expressing concern over the treatment of Maasai, and in June, nine U.N. human rights experts called on Tanzania to immediately halt plans to relocate Maasai communities. In a letter, the experts warned that the removals “could amount to dispossession, forced eviction and arbitrary displacement prohibited under international law.”

The Oakland Institute and Survival International, two nonprofits that advocate for Indigenous rights, called on UNESCO and the IUCN to sever ties with Tanzania and remove Ngorongoro from the UNESCO World Heritage Site list.

The African Commission’s Tanzania delegation is expected to file a final report on their visit to the full Commission and submit findings to the Tanzanian government, but based on the delegation’s initial communique, the Maasai expect shortcomings: the findings only briefly mention the Maasai’s allegations of cattle seizures, and only vaguely mentions concerns about relocations. Samwel Nangiria says that the delegation’s communique is “far from the reality.”

Mathew Bukhi Mabele at the University of Dodoma isn’t hopeful that the Commission can push back against the powerful conservation interests driving the Tanzanian government’s campaign against the Maasai. “They are very much powerless when it comes to these international forces pushing certain agendas,” he said.

When he heard that the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, José Francisco Calí Tzay, would not be visiting in December, Samwel Nangiria was devastated. Now, seeing what happened with the African Commission, he thinks that it was the right decision. “We are grateful that the Special Rapporteur couldn’t be manipulated,” he said.

While the Maasai have called on the Commission to return and conduct a new, fully independent visit, leaders say they have few options. Leaders like Nangiria and Salangat Mako are in hiding, United Nations observers have been sidelined, and, to victims, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights appears to be rubber-stamping the Tanzanian government’s actions.

Nangiria said he sometimes feels guilty for sharing the video considering the attention it drew from authorities and the impact it had on Mako, but Mako has no regrets. “My heart spoke that day,” he said.

Now, the rest of the world has to do their part, Mako said. Especially tourists whose presence continues to drive the campaign against the Maasai.

“We need your voice. We are losing breath,” he said. “Please come to our rescue.”

This story has been updated to include comment from the UNESCO World Heritage Centre.