In early May, a woman in her 90s was hospitalized in Connecticut with a strange assortment of symptoms: confusion, nausea, chest pain, chills, and fever. Two weeks later, on May 17, she died. The culprit was a blacklegged tick, a minuscule arachnid about the size of a sesame seed when fully grown.

Blacklegged ticks, commonly known as deer ticks, carry a wide range of illnesses. They’re best known for carrying Lyme disease, a sickness that causes a rash, fatigue, fever, and other unpleasant, sometimes debilitating, symptoms. The tick that killed the woman in Connecticut was carrying a disease that is far rarer and deadlier than Lyme: It’s called Powassan virus, or POWV. Blacklegged ticks carrying Powassan kill one in 10 of the people who develop severe symptoms. Half of those who survive a serious bout of the illness continue to experience the effects of the disease, such as loss of muscle mass and recurring headaches, for the rest of their lives.

The fatality in Connecticut is the second Powassan-related death in the United States this year. In April, someone in Maine died in the hospital after contracting the illness from a tick bite. Two deaths in the span of a couple of months may not sound like a lot, but they represent what looks like a significant rise in the disease that’s concerning experts. The 134 cases documented in the U.S. between 2016 and 2020 represent a number 300 percent higher than in the previous five-year period. And the cases that are reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, are most likely the symptomatic cases, typically the ones that land people in hospitals.

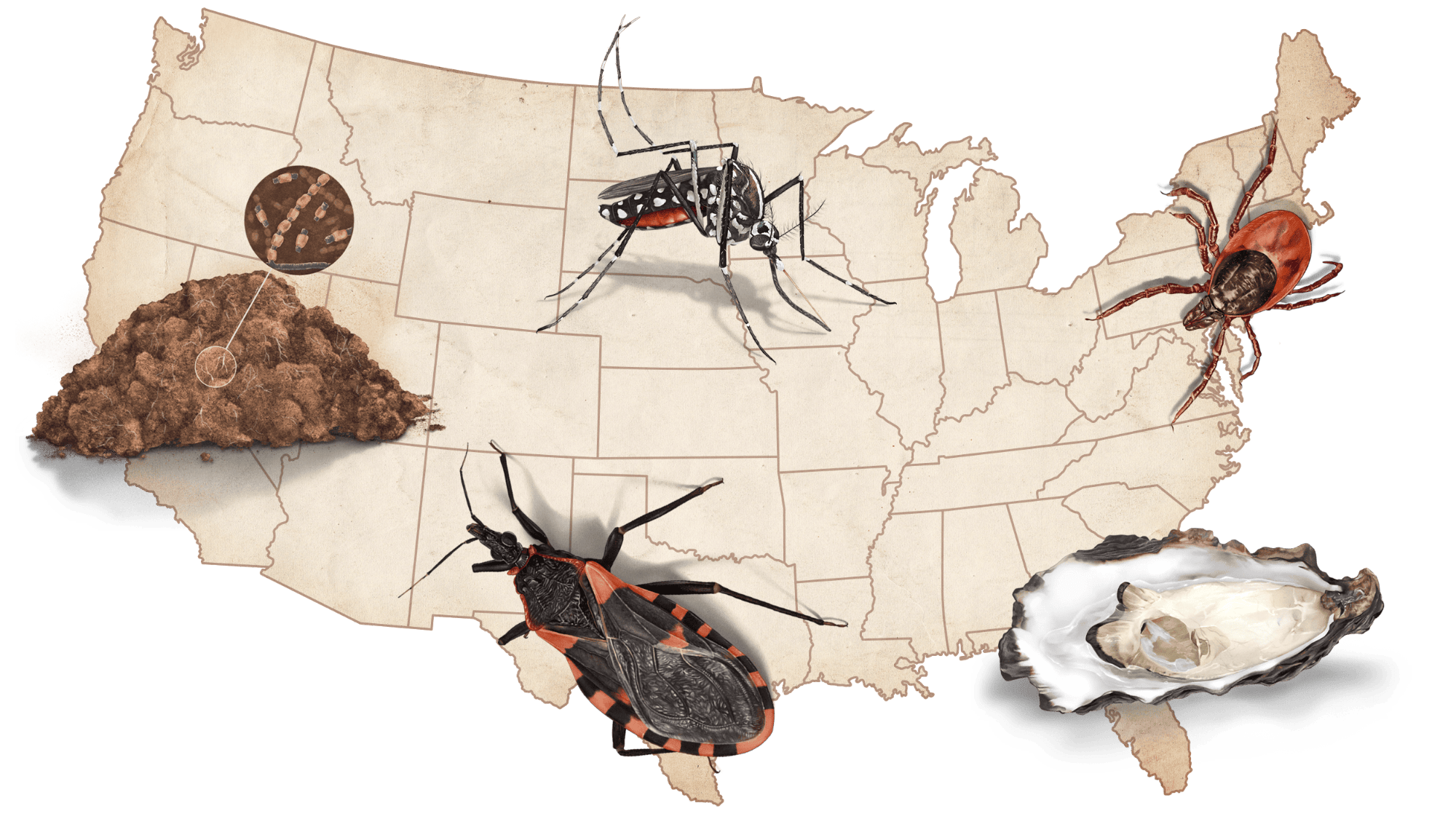

The true extent of the virus’ reach throughout the U.S., experts told Grist, could be greater than what’s reported by the CDC. Many cases of Powassan are asymptomatic and, even when a patient presents with symptoms, doctors may not accurately diagnose the disease because of its rarity. Experts expect cases of Powassan virus, and other diseases that people contract from carriers in the natural environment, to continue to rise as the climate continues to change due to greenhouse gas emissions. Warming temperatures are helping ticks shift their ranges into new areas, and warmer winters are helping the bloodsuckers survive from one year to the next. Most Powassan cases have been diagnosed in the Great Lakes region and the Northeast, but cases have also cropped up in states as far flung as North Dakota and North Carolina.

So when’s the right time to freak out about Powassan virus? Tick researchers have differing opinions on how serious of a public health threat Powassan is at the moment. But the general takeaway is that Powassan is a growing concern, and, if it were to become a more common disease in the U.S., it would be extremely bad news.

In New York state, Saravanan Thangamani, director of the SUNY Center for Vector-Borne Diseases at SUNY Upstate Medical University, runs a tick testing initiative out of his lab. When someone finds a tick in their backyard or crawling up their leg, they can send it off to Thangamani’s lab to have it tested. By cataloging those submissions, Thangamani found that the lower Hudson Valley in New York state has become a hotspot for Powassan virus in ticks. But he still doesn’t know what factors are responsible for the uptick in Powassan virus among the arachnids in that area. In fact, no one even knows exactly where ticks pick up Powassan virus — it’s still an open area of research.

“We don’t know where most of it comes from,” Richard Ostfeld, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in New York, told Grist. “There’s some evidence now that short-tailed shrews might be a very important reservoir host for this,” he said, adding that white-footed mice, skunks, raccoons, weasels, and woodchucks have also been known to transmit Powassan to ticks, which can then in turn bite humans and infect them with the virus. “But we don’t know whether one of those hosts is more important than others in terms of infecting ticks,” he said.

Putting aside how little we know about where the virus comes from, and why the ticks that carry it tend to accumulate in certain areas, Thangamani says his research shows that there’s potential for Powassan to become more common in coming years. “In my opinion, people should be very very concerned,” he said. “There’s potential for it to become a major public health hazard.” Incidents of Powassan virus in ticks he’s tested in the lower Hudson Valley have increased between 3 and 5 percent in the three years that he’s been collecting citizen data. It’s also possible that other tick species, like the American dog tick or the lone star tick, can carry a version of the Powassan virus, too. As ticks continue to expand their range across the country, Thangamani worries that more humans could come into contact with Powassan-carrying ticks.

Ostfeld isn’t so sure that the increase in human cases documented by the CDC is evidence that there’s been a huge surge in the number of ticks carrying Powassan virus throughout the U.S. The increase could be due to more doctors becoming aware of tick-borne illnesses and testing patients for them, random chance, or a number of other factors. “I’m very comfortable saying, ‘yes, it’s very concerning,’ and I’m comfortable saying ‘it looks like it’s probably going up,” he said. “But I’m not going to swear on the Origin of Species that we have a statistically significant trend.”

But Ostfeld emphasized that now is the time for dedicating more resources and attention to understanding Powassan and how it functions in the environment. “It’s very very difficult to get funding from federal agencies for something like Powassan virus because of its rarity,” he said. “But one could argue that its rarity is exactly the time when we should be figuring out more of the basic biology of this virus and which factors influence human exposure so we’re prepared if and when it becomes more common.”

Lack of funding for tick-borne illnesses is an issue the Minnesota Department of Health has run into. In Minnesota, public awareness about Powassan and many other tick-borne diseases is low, public health officials told Grist. But resources to change that, and to expand the state’s understanding of tick-borne illnesses in general, have been stretched thin between many different public health priorities, most notably the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. “We don’t have the resources,” Erin Kough, an epidemiologist at the vector-borne disease unit at the Minnesota Department of Health, told Grist, “but we know that if changes in climate expand the territory of a tick then that means we’re going to get diseases in new parts of our state.”