The year 2010 was a reckoning for Japan’s economic security.

On September 7, the Chinese fishing trawler Minjinyu 5179 refused an order by Japan’s coast guard to leave disputed waters near the Senkaku Islands, which are known in China as Diaoyu. The vessel then rammed two patrol boats, escalating a decades-long territorial feud.

Japan responded by arresting the captain, Zhan Qixiong, under domestic law, a move Beijing considered an unacceptable assertion of Japanese sovereignty. Amid mounting protests in both countries and the collapse of high-level talks, China cut exports of rare earth elements to Japan, which relied upon its geopolitical adversary for 90 percent of its supply. The move reverberated throughout the global economy as companies like Toyota and Panasonic were left without materials crucial to the production of everything from hybrid cars to personal electronics.

It wasn’t long before Japan gave in and let Qixiong go. The crisis, which garnered worldwide attention, became a catalyst for Japan’s push to secure a reliable supply of critical minerals. “That was the turning point,” said Takahiro Kamisuna, a research associate at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London.

Fifteen years later, that reckoning has only deepened.

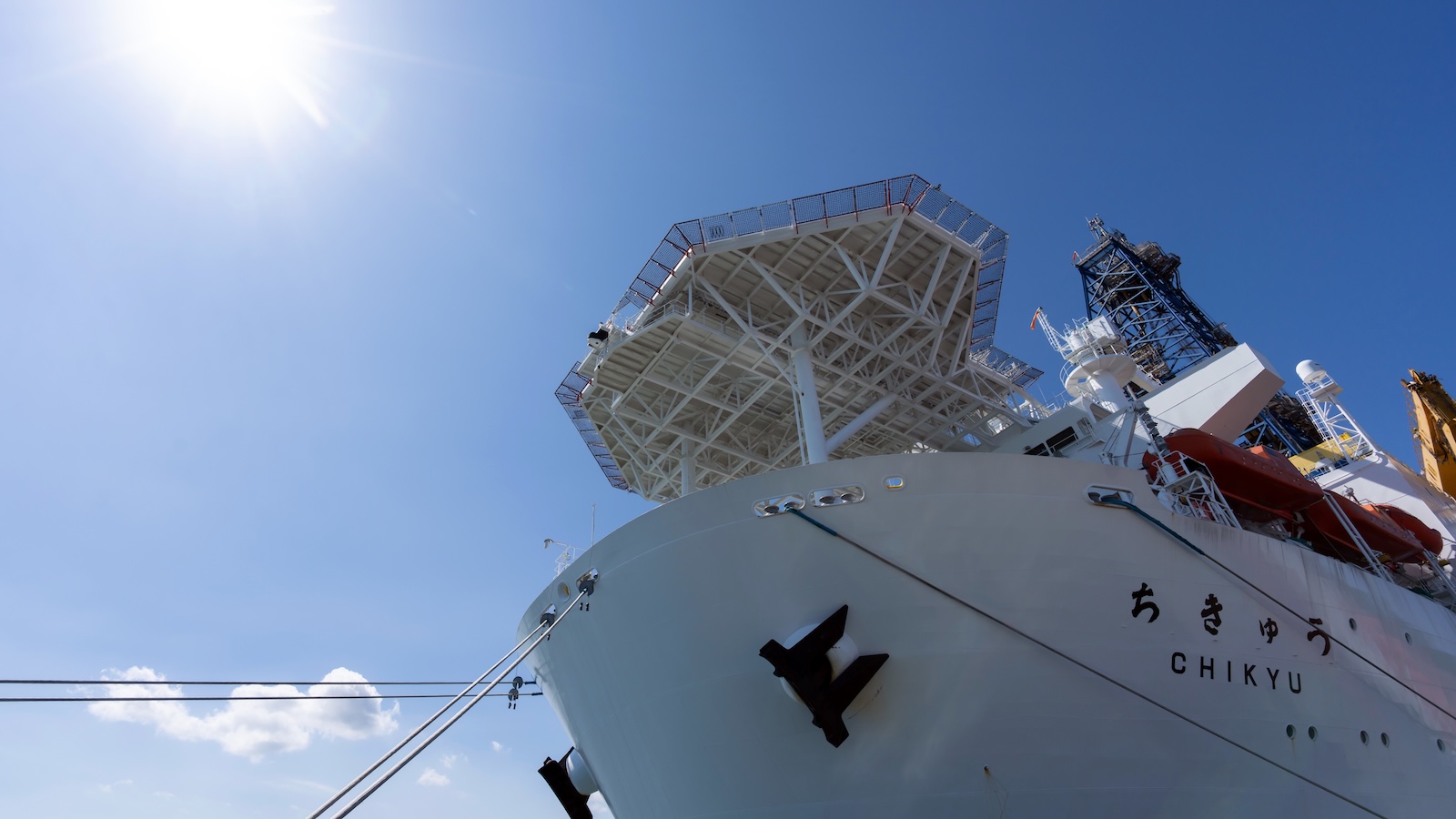

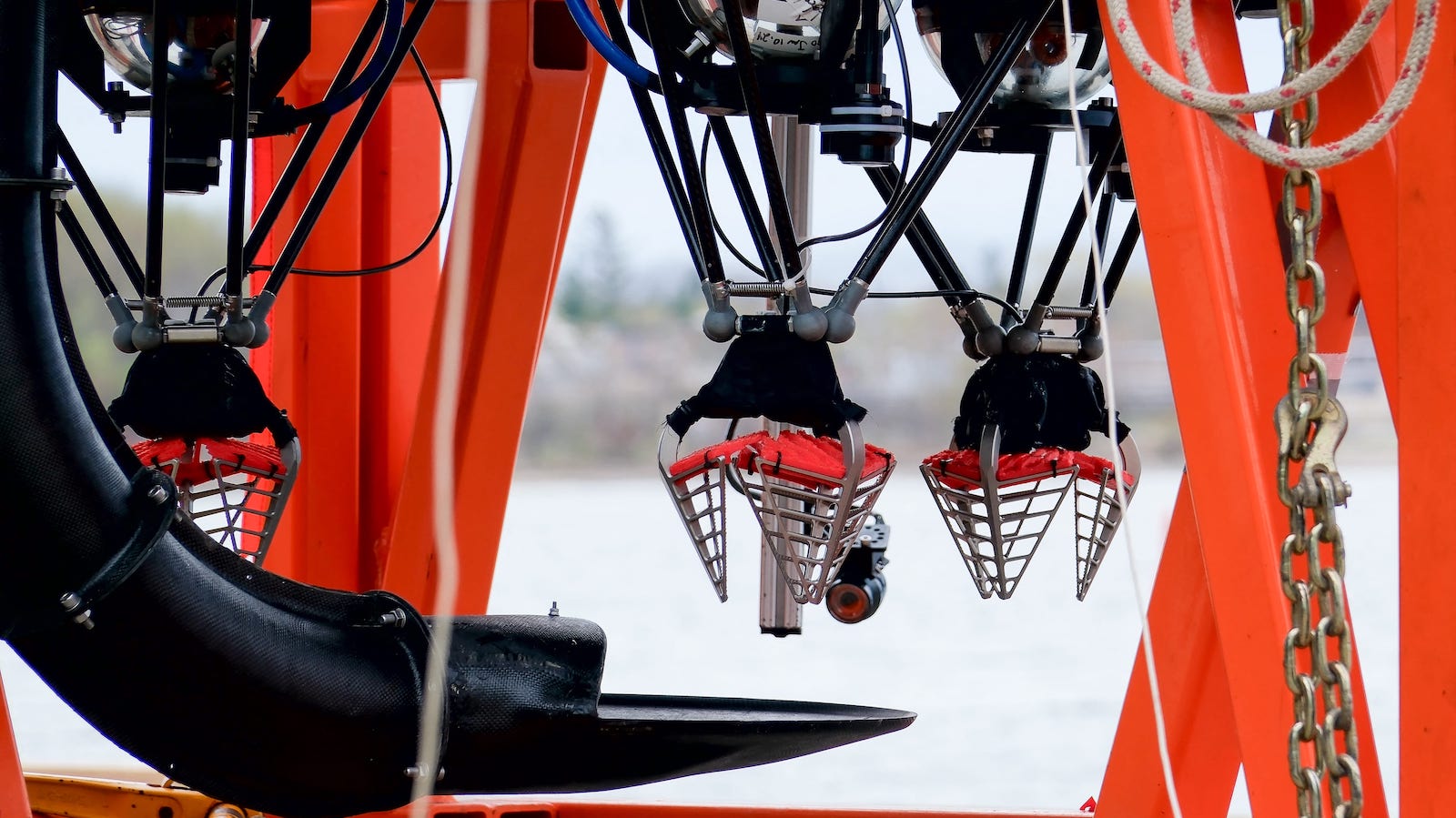

China still provides 60 percent of Japan’s critical minerals, a reliance that has grown riskier as Beijing asserts its position as the world’s dominant supplier. Last month, Japan took a bold step to break that dependence when it launched a five-week deep-sea mining test off Minamitorishima Island. A crew of 130 researchers aboard the Chikyu — Japanese for “Earth” — will use what is essentially a robotic vacuum cleaner to collect mud from a depth of 6,000 meters, marking the world’s first attempt at prolonged collection of minerals from great depths.

Seabed mud off the coast of that uninhabited island, which sits 1,180 miles southeast of Tokyo, is rich in rare earths like neodymium and yttrium — distinct from the potato-shaped polymetallic nodules often associated with marine extraction. Such materials are essential for electric vehicles, solar panels, advanced weapons systems, and other technology.

The expedition, which is expected to end February 14, is being led by the Japan Agency for Marine Earth Science and Technology, which did not respond to a request for comment. It comes three months after the country signed an agreement with the United States to collaborate on securing a supply of critical minerals. It also propels Japan to the forefront of a growing debate over how far nations should go to secure these materials. Deep-sea mining “is not a new thing,” Kamisuna said, “it’s just gaining more attention mainly because of geopolitical tensions.”

The trawler incident highlighted a vulnerability that successive governments vowed to alleviate. Many criticized then-prime minister Naoto Kan of the country’s center-left party for capitulating to China, but he pledged to never again let Japan’s industrial future hinge on a single supplier. His successor, Shinzo Abe of the center-right party, was more aggressive and saw critical minerals as not just an economic issue, but a matter of national security that must be addressed even if it meant exploiting the deep sea.

Establishing a domestic supply could help Japan reach its goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, a high priority for Yoshihide Suga, who succeeded Abe. Although Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, an Abe protégé who assumed office late last year, supports the 2050 timeline, she has said the transition must not risk Japan’s industrial competitiveness and energy stability.

Takaichi has proposed slashing subsidies for large-scale solar projects or batteries, largely because so much of that technology is imported from China. Instead, she has hailed nuclear power as the path toward carbon neutrality. With the mining experiment unfolding in the Pacific, Takaichi hopes to secure a strategic reserve of minerals to protect key industries.

But Japan doesn’t face an either-or choice, said Jane Nakano, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. “Energy security and energy transition are closely tied,” she said.

“To me, it’s much more about the pace, not so much the direction,” said Nakano, who has worked for the U.S. Department of Energy and for the energy attaché at the U.S. embassy in Tokyo. “I don’t find Takaichi’s way of framing this dual challenge — energy security and decarbonization — unique to Japan. A lot of G7 countries are starting to recalibrate again, so they do have to think about international competitiveness. Direction-wise, [Japan] is just aligning itself with the political establishment and the industry.”

Unlike China, Japan lacks the sedimentary geology associated with rare earth deposits, requiring it to look toward the waters within its exclusive economic zones. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Japan has the right to exploit the resources within 200 nautical miles of its coastline, which includes the atoll island of Minamitorishima.

Although the minerals to be found there lie nearly 20,000 feet beneath the surface, proponents of digging them up argue the challenge of extracting them and the cost of refining them is justified by mounting geopolitical tension. With Takaichi’s recent political jabs at Beijing, China has begun choking off its exports to Japan. Nakano said Japanese officials seem “confident” in the outcome of the experiment. “They’ve determined that it merits to have this demonstration of technologies and equipment this time around,” she said.

Japan’s foray into deep-sea mining comes amid mounting concern about the ecological cost of such technology. Scientists and environmental groups warn that marine extraction is racing ahead of our understanding of the impacted ecosystems. They are particularly concerned about sediment plumes, noise and light pollution, and damage to habitats and food webs, noting that scars left by equipment could render the seafloor uninhabitable for decades, even centuries.

“A tiny little nudge, and the whole seafloor is disturbed,” said Travis Washburn, a marine biologist at Texas A&M University in Corpus Christi. He studies deep-sea environments and human impacts on marine ecosystems, and he has analyzed the waters around Minamitorishima Island and represented Japan at International Seabed Authority workshops. He believes that mining rare earths from mud could have the same impact as mining nodules. “I think that they’re both pretty much going to destroy the habitat directly affected.”

Government officials insist the ecological impacts will be closely monitored. But assessing them could be difficult, because the seafloor around the island, home to sea cucumbers, sponges, corals, and potentially rare endemic species — remains the subject of intense study. Scientists fear these ecosystems may be permanently altered before anyone assesses them. As with many extractive industries, Washburn noted, technology is often deployed before anyone fully understands its environmental impacts.

Shigeru Tanaka, deputy director general of the Pacific Asia Resource Center, is an outspoken critic of deep-sea mining. He argues that the industry as a whole disregards international law and that exploiting the seafloor will harm fisheries and trample upon the rights of Pacific Islanders who consider the sea as sacred. (The Indigenous people of the Mariana Islands have raised such concerns in opposing Trump administration plans to open the waters there to mining.) He also believes that some of the experts involved in Japan’s project “are not really taking seriously the risks to the environment and how irreversible it may be.”

Even some government officials have expressed concern. Yoshihito Doi of the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy has said Japan should mine only “if we can establish a robust system that properly takes environmental impacts into account.”

William West / AFP via Getty Images

It remains unclear what exactly is unfolding beneath the waves during this current test, but based upon his experience working with the Japanese government on similar research, Washburn said the top priority will be assessing whether the technology works. Researchers also will monitor how much material the system can hold and if the machinery can keep the sea mud contained without releasing a massive sediment plume on the seafloor or in the water column.

If Japan can successfully deploy a 6,000-meter pipe that can suck up 35 metric tons of mud under extreme pressure — about 8,700 pounds per square inch, or 600 times the pressure at sea level — government officials say a broader trial, which may include polymetallic nodules, could begin in February 2027.

One longer-term goal is to develop what’s called “hybrid mining.” Because deep-sea polymetallic nodules sit atop the rare-earth mud around Minamitorishima Island, researchers are exploring whether both could be collected and separated in a single operation.

Kamisuna said Japan faces another challenge: The energy needed to acquire and refine a stockpile. “If we want to create a sufficient reserve for rare earth [minerals], either using domestic or export, a large amount of electricity is required,” he said. “And the question is, What are we going to use, liquified natural gas or coal? What is the environmental cost?”

Using more environmentally friendly methods of extraction and processing can be expensive, he said — which is one reason many countries turn to China as a cheaper option.

For now, Japan’s deep-sea mining experiment seems to have drawn little public opposition at home, unlike in the United States and Australia where environmental activists and Indigenous communities have pushed back against such operations, particularly around the Pacific Islands. In the meantime, the country’s test moves forward, even as the implications of success, and questions about its long-term impact, remain unresolved.

“We are not prepared,” Tanaka said. “My personal take is that by the time we are ready, when the technology and the science is set, I really do not think there would be a demand for it.”