This post has been updated to include additional perspectives.

“The mountains are calling,” says a post by Pattie Gonia, an Instagram personality and — according to her bio — the world’s first backpacking drag queen. “They want their femininity back.”

Despite monumental steps toward LGBTQ equality over the past 20 years, many in the outdoor community — including Wyn Wiley, the outdoor enthusiast behind Pattie Gonia’s Instagram account — say they still don’t see themselves reflected in outdoor culture. “Gay things” felt relegated to the city, Wiley explained in an Instagram post. Out on the trail or on the mountain, there was little room for rainbow flags, Ariana Grande, or the patent leather boots with 6-inch heels that have become one of his alter ego’s signature fashion statements.

But Wiley and others are claiming space for themselves in the outdoors — with pride. “When you live unapologetically, the world is on your terms!” Wiley wrote in the caption for Pattie Gonia’s first Instagram post in October 2018. Twirling hiking poles and dancing to Fergie’s “London Bridge,” Pattie entreated her fans to embrace their authentic selves. “Go for that thing and fall the f down,” she said. “Get back up. Climb a mountain. Hell, maybe even wear heels on top of it. Who cares, hunni, do you!!!”

That’s an ethos that the broader outdoor community is beginning to embrace. Over the past five years, new groups like the Venture Out Project and Out There Adventures have helped show LGTBQ youth and adults that there is enough space in the great outdoors for everyone. In 2017, REI hosted the first-ever LGBTQ Outdoor Summit. Even the climbing community — notoriously perceived as overwhelmingly heterosexual — has an annual HomoClimbtastic rock climbing festival.

“Queer people have always been doing these things,” said Lance Garland, a journalist and firefighter in the Pacific Northwest who identifies as gay. Hikers, backpackers, climbers — LGBTQ adventurers have been out there forever. What’s new, he said, is that people are now eager to tell, seek, and celebrate stories that go beyond the stereotype of the straight, white, male nature lover.

Journalist and firefighter Lance Garland poses at the summit of Tower Mountain in the North Cascades. Courtesy of Lance Garland

Social media has helped, he added, amplifying the voices of people who don’t typically get as much press attention. Take Jenny Bruso, for example, an activist who was featured on the Grist 50 list in 2019. Her Unlikely Hikers Instagram account has garnered almost 100,000 followers and features “people of size, Black, Indigenous, People of Color, queer, trans, and nonbinary” folks on the trail. Pattie Gonia, for her part, has attracted a whopping quarter million followers in just under two years.

Not long ago, many outdoor enthusiasts said they didn’t know of any openly LGBTQ role models who were out hiking, biking, and rock-scrambling. For Mikah Meyer, a native Nebraskan who in 2019 became the first person to visit all 417 National Parks Service parks, something as simple as representation can make a huge difference in creating a welcoming environment for non-heterosexual adventurers.

“You can’t be what you can’t see,” he told Grist, quoting the civil rights leader Marian Wright Edelman. And what you do see most frequently in advertisements, he added, is a very specific image of what an “outdoorsman” should be: He’s male. He’s wearing a flannel. He has a beer in hand. “And he’s always straight,” Meyer said.

As a gay man growing up in the Midwest, Meyer said it was difficult to find LGBTQ role models that he could identify with. He didn’t meet an openly gay man until he left Nebraska for college. Even in 2017, as Meyer searched for a corporate sponsor for his three-year quest to visit all 417 parks, he couldn’t find any vocal LGBTQ people representing a major outdoor brand.

“The implicit message that I got was that outdoor culture does not want gay people involved,” he said. That was true for one of his early sponsors: As soon as Meyer began using his trip to advocate for LGBTQ issues, they told him it was too much and dropped their sponsorship. He was later picked up by REI as an ambassador for their #OptOutside program, and would go on to consult for the company’s LGBTQ programming.

Mikah Meyer visited all 417 National Parks Service parks on a 3-year-long road trip. Courtesy of Mikah Meyer

However, Meyer says that his outward appearance has made it relatively easy to be gay in the outdoors. “I have the privilege of being able to pass as a straight white man,” he said.

That isn’t the case for many in the queer community, including Appalachian Trail thru-hiker Lucy Parks, who is nonbinary and transgender and uses they/them pronouns. Parks calls themselves a “100-footer,” meaning their LGBTQ status can be spotted from 100 feet away.

“I’m a very visibly queer person,” Parks said. “For a long time, I didn’t really see thru-hiking as an option.” Growing up in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, Parks had always loved the outdoors, and ever since they read Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods, they had wanted to hike the entire length of the Appalachian Trail. But hearing about the 1996 murder of a lesbian couple in Shenandoah National Park — not far from where Parks grew up — gave them pause. “If I go out in the woods looking the way I look, what are people going to do?” they wondered.

Parks completed the AT last year. Although some people were dismissive of their pronouns and gender identity, others were eager to welcome Parks into the trail community. Mostly, Parks said, the trail was a therapeutic and restorative space, free from many of the societal constraints that plague nonbinary folks. “Many of us can’t enter a gender-divided bathroom without trepidation,” they wrote in Outside Online. “In the woods, of course, you can pee wherever you want.”

Eva Kloiber, a queer trans woman and a leader for the volunteer-run organization Seattle Queer Climbers, also sees liberation in the outdoors —the deep concentration required in rock climbing and mountaineering offers an amazing sense of freedom, she said. When routing your way up a mountain or scrambling to the top of a 15-foot rock, you can momentarily forget about the worries of daily life.

At Seattle Queer Climbers, which was founded in 2015 by Kloiber’s partner, Kloiber helps connect the LGBTQ climbing community through monthly meetups and regular climbing trips to local crags. Kloiber is proud of the work the group has done to affirm that the climbing gym, crag, or mountain can be a safe space for queer and trans people. “The intimidation of going into a climbing gym as a new person is extreme,” she said, “and doubly so for someone who doesn’t conform to society’s gender or sexuality expectations.”

Eva Kloiber is a leader with Seattle Queer Climbers, where she helps organize monthly meetups and regular trips to local crags. Courtesy of Eva Kloiber

Outdoor writer* and nature enthusiast Aer Parris, who identifies as queer, stressed the importance of this kind of active affirmation. “The outdoor community somehow believes that it is not political,” they said. In a way, that’s understandable, Parris added — people go into the outdoors to get away from things, to rest and rejuvenate. That’s partially what drew them into a cross-country bike trip a few years ago, and later into the Seattle mountaineering community. But that doesn’t mean LGBTQ equality should be off-limits for trail talk. “When an entire community is pretending that politics are not part of the outdoors,” Parris said, “you’re unable to have conversations that could create change.”

Travis Clough, director of trail operations for the Venture Out Project, says he often hears people say, “Nature doesn’t care if you’re gay.” But Mother Nature isn’t the problem. “We’re talking about all the assholes on the trail,” he said. “I can’t do anything if I don’t feel safe.”

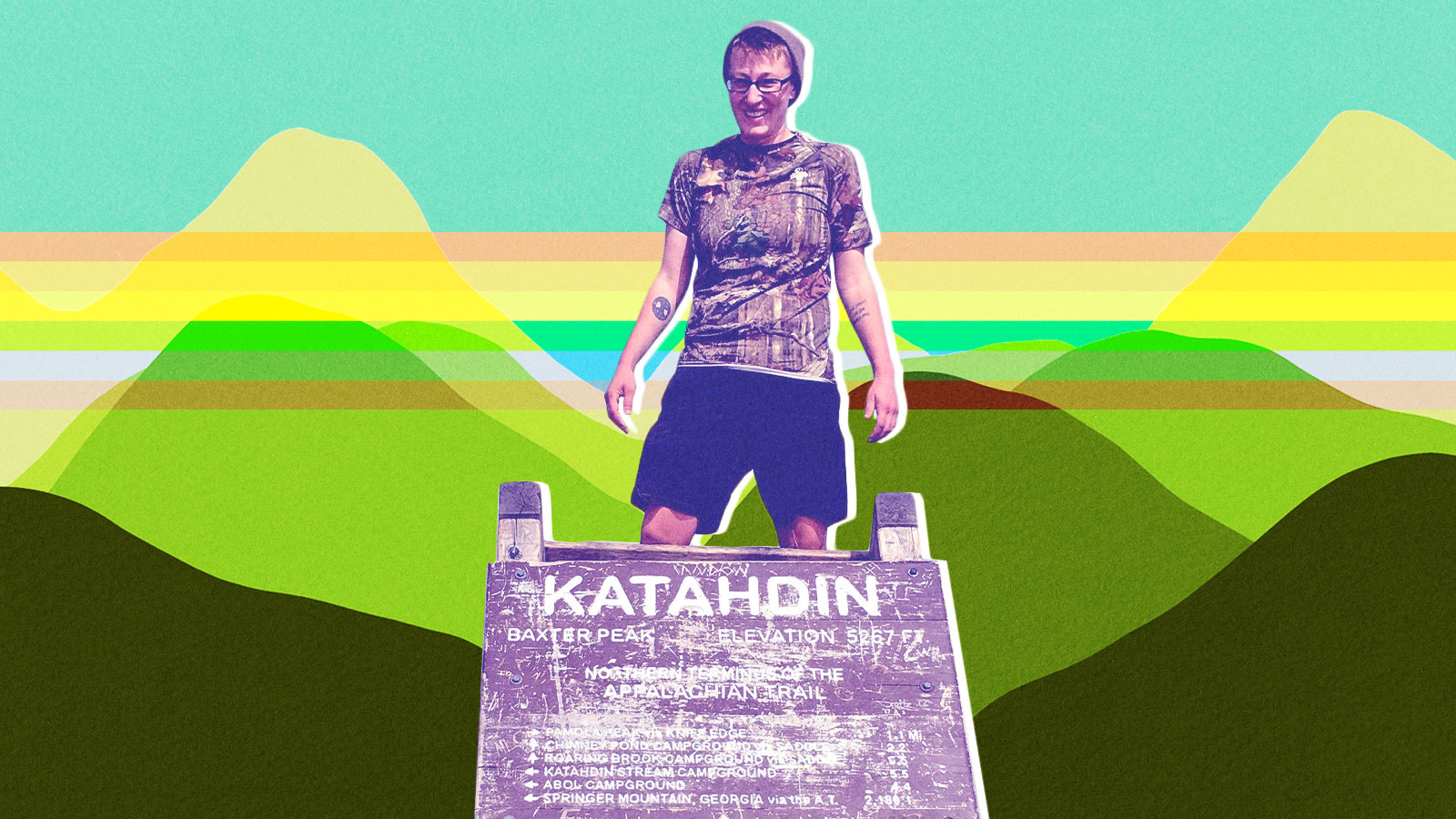

Travis Clough (far left) helps coordinate trips for the Venture Out Project. Here, he leads a group up Maine’s Mount Katahdin. Courtesy of Travis Clough

The only way to combat these issues, Clough says, is to continue working on LGBTQ visibility, creating safe spaces for hikers of all genders and sexualities through programming and education. Parris also points to the need for a holistic, intersectional approach to outdoor equity. “We need everyone together,” Parris said. “If you’re not seeing BLM in your outdoor spaces, trans lives matter, immigrant lives matter — you’re not seeing a whole swath of people who are not able to access the outdoors in the same way.”

That resonates with Jasmine Maisonet, who identifies as queer and founded the social media community QPOC Hikers in 2019 after moving to Seattle from San Diego. Maisonet had been an avid hiker in Southern California, taking advantage of the year-round good weather to hike 52 hikes in 52 weeks. When she moved to Seattle, she wanted to continue hiking with other queer people of color. “But the Pacific Northwest is primarily white,” she said. “Hiking itself and outdoor spaces are primarily white.”

Maisonet —who is Puerto Rican and grew up in New York — said she has often experienced racist stereotypes about who belongs in the outdoors. When she founded the Facebook and Instagram pages that have since developed into the QPOC Hikers community, she wanted to work against these biases. She began by posting group hikes on Facebook, not anticipating a big turnout. But the group’s reception has exceeded her expectations — on each hike she’s been joined by several members of the Seattle-area QPOC community. “It’s been incredible to see,” she said.

Jasmine Maisonet runs a Facebook and Instagram community called QPOC Hikers and organizes hikes in the Seattle area. Courtesy of Jasmine Maisonet

Colorado-based Queer Nature adds an educational element to bringing the queer community outdoors. The program teaches skills like leather-making, wildlife tracking, and situational awareness to deepen people’s connection with nature.

“Queer Nature is a love story,” said cofounder Pınar Sinopoulos-Lloyd. Not only a love story with their partner and cofounder So Sinopoulos-Lloyd, “but an interspecies love story with our ecological kin.” After growing up frustrated by outdoor narratives of colonization, categorization, and exclusion, they started Queer Nature as a way to build solidarity not only within groups facing systemic marginalization — including Black and Indigenous communities — but with the rest of the natural world.

Pınar and So say they have watched a beautiful and resilient community coalesce around Queer Nature in the six years since they started the program. They hope it will continue to invite people to challenge dominant narratives about our relationships with each other and with nature. “My prayer,” said Pınar, “is for us as queer people — and as humans — to remember how to listen to our more-than-human relatives while respecting whose First Nations’ lands we are on. Our co-liberation depends on it.”

Pınar Sinopoulos-Lloyd and So Sinopoulos-Lloyd co-founded Queer Nature six years ago. One of the classes they lead with the program is called Queer Stealthcraft — the art of blending into your surroundings. (Pınar is in the middle without camouflage.) Courtesy of Queer Nature

Other people in the queer community have faced physical barriers to accessing the outdoors. That’s in part what inspired Syren Nagakyrie, who identifies as queer and disabled, to start the organization Disabled Hikers in March 2018. “My experience in outdoor culture has been really frustrating,” they told Grist. Nagakyrie has Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, chronic pain, fatigue, and other conditions that can make hiking painful and difficult. “I have often felt alone as a disabled queer person in the outdoors,” they said.

Nagakyrie loved getting outside, but was frustrated by guidebooks and trail postings that lacked sufficient accessibility information. What are the trail conditions? Would there be benches along the way? Nagakyrie launched Disabled Hikers as a way to counter the pervasive ableism of the outdoor community, and they’ve been heartened by its reception —the Instagram account has nearly 7,000 followers, and it has connected Nagakyrie with a wider community of disabled hikers. Nagakyrie also built a database of trail information for hikes across the Pacific Northwest, and they are in the process of writing a book, The Disabled Hiker’s Guide to Western Washington and Oregon.

Syren Nagakyrie, founded Disabled Hikers in March 2018 to work against outdoor ableism. They are currently working on a book, The Disabled Hiker’s Guide to Western Washington and Oregon. Courtesy of Syren Nagakyrie

There is still work to do, and the outdoor community is nowhere near as diverse or inclusive as it should be. But many LGBTQ outdoorspeople are hopeful that the recent upswing in visibly queer role models in the outdoors will start to turn the tide, letting others know that they are welcome in the wildest wildernesses.

“Even if you don’t see exactly who you are represented in your social media or in books or in pop culture,” said Garland, the firefighter, “just go be that person. Right now in the outdoors industry, we’re having the opportunity to be trailblazers.”

*Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly described Aer Parris’ job. They are an outdoor writer.