In a square patch of dirt in my childhood backyard in California, my dad decided to plant a little piece of Mexico. There weren’t but a half dozen rows of white corn, but he tended to those stalks the same way he cared for the tiny jungle of potted plants he lined up around our patio: methodically and with care. “Around and around,” he’d remind me as I guided the hose from plant to plant, trying not to drown the mix of citrus trees, hibiscus plants, ferns, and other species that my dad grew as part of his landscaping business. It was one of my least favorite daily chores, but now I realize how my father used those moments to pass on small lessons about how to care for the world around us.

My dad worked as a gardener for Santa Barbara’s well-to-do, and my sisters and I helped him with tasks like weeding and raking after school and on weekends. It was a purposeful decision by my parents to instill a work ethic in us. In Mexico City during the 1960s, my dad owned a small chain of tortilla mills that he supplied with corn he bought directly from local farmers in the states surrounding the country’s capital.

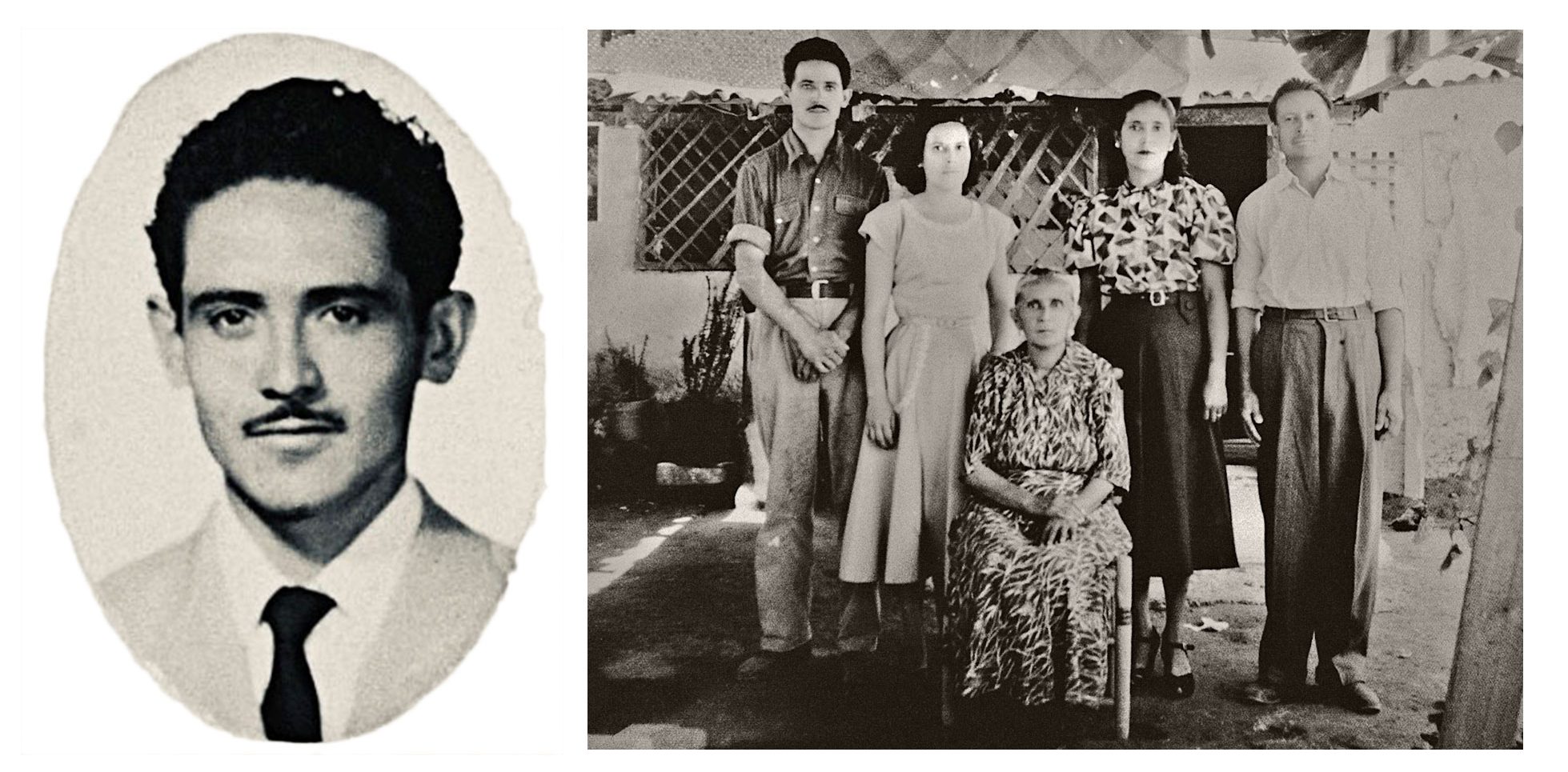

Family photos of the Cabrera family from the late 1940s or early 1950s show the author’s father, Gabriel Cabrera, back row, left, in Santa Barbara, CA. Courtesy Yvette Cabrera

Although I was not born in time to witness this era, my dad would talk often about his battle to improve the quality of tortillas sold to the public. Corn, both a basic staple of the Mexican diet and a symbol of the country’s indigenous roots, allowed my dad, who grew up poor and never went to college, to become a successful entrepreneur. Yet, while he won the battle — producing some of the finest tortillas in Mexico City at the time, with lines of customers winding around city corners — he ultimately lost a war with the Mexican government, and this eventually drove him out of business. He immigrated to the United States to start fresh, but he never lost that connection to the land: His springtime plantings would produce a bounty of fresh corn for us in the summer. When I was in high school, we moved on to plant a full-fledged garden. My mom would pluck the blossoms off the squash we grew, simmer them in tomatoes, onions, and chiles, and then tuck it all into a handmade tortilla.

My parents taught me early not to waste, because we had little to spare. Later, as an adult reporting stories along the U.S.-Mexico border, I came to see just how ingrained this value is among Mexico’s working class. It’s reflected in how they squeeze the most from the food they have. In Tijuana, along the hillside shantytowns where residents tended their own corn patches, I watched in awe as one grandmother scraped the fungus known as huitlacoche, which grows on corn kernels, and added it to the gooey, melted cheese of the quesadillas she made the day I visited. What I might have initially dismissed as ruined, moldy corn was actually a mushroom-flavored delicacy prized by the Aztecs.

Earlier this year, I wrote about how Latinos, and Mexican-Americans specifically, are inclined toward environmentalism because of their deeply-rooted conservation practices. After publishing that story, we asked Grist readers to share their own family environmental histories: the customs, habits, and practices that taught them how to reuse, recycle, and waste less.

The responses illustrated how important these lessons have been in shaping how our readers live today. Laís Santoro, a rising sophomore at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, noted that her Brazilian grandmother never throws away overripe bananas. Instead, she uses them to make Santoro’s favorite dessert, frying the bananas and sprinkling them with cinnamon and nutmeg.

Amelia Bates / Grist

“Those little things really taught me that we cannot waste because there’s always a way to use what you have. There’s always a way to make a more conscious choice in your life to consume what you need and what you’re going to use, so you minimize the new material things put into the waste system,” wrote Santoro, 19, who is studying public health and environmental studies. Santoro is involved in numerous environmental organizations, including the youth-led Sunrise Movement.

Another reader, Priscilla Solis Ybarra of Texas, shared the ways that her parents modeled conservation throughout their lives. These lessons inspired her to write her 2016 book, Writing the Goodlife: Mexican American Literature and the Environment, which documents Mexican-American contributions to environmental thought in literary history. I reached out to Ybarra, who is an associate professor and director of graduate studies in the English department at the University of North Texas, and we spoke about how her parents shared their knowledge organically — and in doing so broadened her concept of community.

A photo from the early 1940s shows Priscilla Ybarra’s family standing in a sugar beet field in Michigan. Courtesy Priscilla Ybarra

Priscilla’s mother, María Higinia Solis Ybarra, was born in 1938 in a rural agricultural community in the northern Mexican state of Tamaulipas, where she lived on a communal ejido. The Mexican government distributed these parcels of land to peasants as part of a massive land reform effort after the Mexican Revolution, allowing families to farm lands held in common by their village. María, who was raised by her aunt, learned not only to work the land, growing watermelons and cotton, but also how to create herbal remedies and natural healing techniques from the plants that grew on the ejido. María brought that knowledge with her when she moved to Texas in search of her mother, who had abandoned her shortly after her birth.

At home in the United States, María gardened using local species. She used her herbal remedies to care for family and friends: manzanilla tea (chamomile) for colds, coughs, and sore throats; chewing tree bark to strengthen teeth; even an herbal remedy for menstrual cramps that Ybarra said was especially popular with her friends.

Amelia Bates / Grist

“My parents just lived in a way that showed me at every turn that when somebody needs help, and you’re able to help them, you need to do that,” said Ybarra.

Ybarra’s father, Encarnacion Peña Ybarra, was a Texas-born Mexican-American migrant farmworker during the Great Depression who later became a truck driver for Affiliated Food Stores. At home, Ybarra described her father as a “re-use warrior” who took the time to fix the family’s broken appliances and cars himself, loved building things using spare materials, and salvaged scraps from jobs he took tearing down old buildings. Encarnación, who came from a family of 12 siblings, learned how to survive a life of scarcity while traveling the migrant farmworker circuit. It was a childhood marked by struggle, which shaped him into a young man who looked out for others, extending a helping hand to family, friends, and strangers.

Ybarra recalls once walking through her front door to find a young, bandaged man on her parents’ couch. Her father had come across a car accident on the road and learned that the young man, Diego, was undocumented and didn’t have money to pay for hospital care. So the family nursed him to health, and to this day he remains a family friend. After Encarnación died in 1991, Diego would even show up at María’s house to mow her lawn, according to Ybarra.

Amelia Bates / Grist

While her parents emphasized and supported their children’s formal schooling, they also made sure to expose them to practices from their own upbringing that bound them to the land. Sometimes, for example, they’d spot a cornfield along the road and would pull over to ask the owner if the family could hand-pick corn. This was meant to give the siblings a glimpse of what their parents went through to support themselves.

The relationship that Mexican-Americans have with the land was something that Ybarra didn’t see reflected in her university textbooks. This was something that she sought to rectify through her own writing and teaching, integrating the idea that we have much to learn from communities that we don’t conventionally think to learn from.

“Yes, we can invent new ways to be and to exist together. But we can also build on existing traditions of thought, practices, and cultures that have been doing it for 500 years,” said Ybarra, who also co-edited the 2019 book Latinx Environmentalisms: Place, Justice, and the Decolonial. She cites the work of Kyle Whyte, a Michigan State University professor of philosophy and community sustainability who focuses on climate, environmental justice, and indigenous environmental studies. He advocates looking to long-held practices of the world’s indigenous peoples in order to address climate change.

“If we want to look to how we can do this in the future, we have whole cultures who have been teaching us how to do it for a really long time. We just haven’t been paying attention,” said Ybarra.

Indigenous peoples remain important environmental stewards, she said. While they represent less than 5 percent of the global population, they manage about 25 percent of the world’s land, which supports about 80 percent of the planet’s biodiversity. Ybarra adds that addressing climate change is not a matter of extracting this knowledge. Instead, it’s a matter of listening to and learning from native communities — and placing those who already have this knowledge in leadership roles.

Whether we return to ancient indigenous land management practices — or just the practices of our parents and grandparents — it’s clear we can learn so much by paying attention to and practicing those “old ways.” Other Grist readers pointed out that they too practice the customs of those who came before them. Reader David Wootton shared that, like his father before him, he lives modestly in a 1,000-square-foot house that he paid off 44 years ago. He retired almost two decades ago, drives very little, and spends eight hours a day gardening. Now, in his mid-70s, he reports that he has no aches and pains and has all he needs at home. Reader Shevawn Von Tobel wrote that she inherited her green thumb from her grandfather, Victor Gonzalez, who maintained a large garden in his home in California’s San Fernando Valley, where he placed large barrels around the yard to catch and save water.

Amelia Bates / Grist

I definitely did not inherit my father’s green thumb. (Between work and more work, my houseplants only survive because my husband usually steps in to resuscitate them.) But it was no accident that my journalism career led me to Grist to cover environmental justice issues. I know how imperative it is that every person has access to clean air, water, and land. I know my dad would have wanted me in this fight against global warming. He may have fought a different battle, paying for the best corn to create a quality tortilla for the public in Mexico City. In the process, he supported the corn farmers, who in turn could make a living practicing the indigenous farming methods of their ancestors. It was a small triumph, and it was the reason, I believe, that he planted that patch of corn in our backyard: to connect him to those roots.

My dad died of pancreatic cancer years ago, and it was only then, while I cared for him during his last months alive, that I realized that it was my dad who instilled in me a love for storytelling. I didn’t notice until he reached the point when he was too sick to tell those stories anymore, and I missed hearing his voice. My dad may not have received a college degree, but he learned from life and passed those lessons on to me.

A photo of the author’s father, Gabriel Cabrera, from when he worked as a gardener in Santa Barbara, California. Courtesy of Yvette Cabrera

Last year I moved back to Santa Barbara to be closer to my family, but I also came back because my roots stretch deep into the land as well. Outdoors, my dad is with me in spirit: in the whiff of newly-cut grass, in the earthy scent of freshly watered soil, and in the early morning mist that blankets the Santa Barbara foothills, reminding me of the childhood trips we took through the jungles of Mexico. Every day, these remind me that his lessons are still with me.

Ybarra sums it up best in Writing The Goodlife when she says: “We can learn so much by paying attention to those around us, even if — or especially because — they are not the ones we conventionally look to for wisdom and insight.”