Indigenous peoples have a critical role to play in the fight against climate change. Though they make up just 5 percent of the world’s population, their lands encompass more than 80 percent of global biodiversity. Indigenous lands are also at greatest risk from the multiple threats posed by climate change: rising sea levels, warmer temperatures, invasive species, and more severe weather. Indigenous people in the U.S. have been at the forefront of climate planning, using their unique status as sovereign entities to develop ambitious climate change adaptation and mitigation plans for their lands.

Native Americans make up about 1 percent of the U.S. population, but they’ve long been underrepresented in Congress. Since the founding of the country, just 23 Native Americans have served in the legislative body. That slow pace is starting to pick up, however. The 2020 election resulted in victories for a record six Native Americans who will serve as voting members of Congress. Four were reelected, and two were elected for the first time, bringing the historical total to 25.

The victors represent Hawaii, New Mexico, Kansas, and Oklahoma. An additional three representatives from the territories of Guam, American Samoa, and the Mariana Islands are non-voting members. Split between the two parties, the voting members’ views span the ideological spectrum — from Representative-elect Kai Kahele, a Democrat from Hawaii and an ardent supporter of the Green New Deal, to Representative-elect Yvette Herrell, a hard-line conservative and Trump ally who has called the Green New Deal a “radical government takeover.”

“It’s a good thing,” Kahele said of the diversity of opinions within the Native American caucus. “We’re there to work together, and Native American issues and Native Alaskan issues and Native Hawaiian issues are very much the same.”

Indigenous representation in Congress first surged two years ago, after the 2018 midterm elections. Deb Haaland, who is an enrolled member of the Pueblo of Laguna and has Jemez Pueblo heritage, was elected to represent New Mexico’s first congressional district. Sharice Davids, an enrolled member of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, was elected to represent Kansas’ third congressional district. Both Democrats were reelected this month.

From rising sea levels and dying coastal ecosystems to drought and crop losses, the six House districts that will be represented by Native Americans next year face a variety of imminent threats from climate change. Here’s how these representatives plan to tackle the unique climate challenges faced by their constituents.

New Mexico

Native Americans make up 30 percent of New Mexico’s population, but they have accounted for about half of the state’s confirmed COVID-19 cases. Representative Deb Haaland was alarmed by this disparity, but it did not surprise her. Native communities suffer disproportionately from bad indoor air quality, and asthma rates in Native American and tribal populations are almost twice the national average, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). A deadly pandemic involving a respiratory disease was bound to take an outsize toll on these communities.

“If you’re breathing polluted air every single day and then a respiratory virus comes through, it stands to reason that it’s going to affect the population there,” Haaland told Grist.

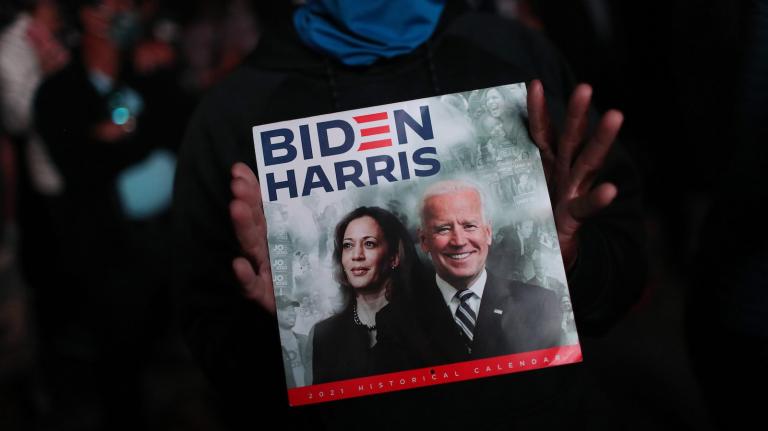

Haaland is vice chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources, and she wants to push for more renewable energy in her district. During her second term, Haaland said she hopes to stop the leasing of public lands to fossil fuel companies. She’s hopeful that the incoming presidential administration of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris will take environmental justice seriously by investing in clean infrastructure and targeting policies to help the most at-risk communities. Haaland praised the Biden-Harris climate plan for promoting greater access to medical care, housing improvements, and green infrastructure in tribal nations.

“The Biden administration has the most progressive platform for our earth and the climate ever,” she said. On Tuesday, The Hill reported that Biden’s transition team was vetting Haaland for a possible cabinet appointment as Secretary of the Interior.

Yvette Herrell, an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation who is the representative-elect for New Mexico’s second congressional district, is seemingly Haaland’s polar opposite.

“I will work with President Trump to reduce job killing regulations, cut taxes for our middle class, and rebuild our rural economies by opening the door to logging, mining, and expanded energy production,” the Republican tweeted in May.

Hawaii

From rising seas to dying coral reefs to decreased rainfall, Hawaii is experiencing some of the starkest effects of climate change. Democratic Representative-elect Kai Kahele is sensitive to the ways in which a warming planet threatens Hawaiins in general, and Native Hawaiins in particular.

“The entire Pacific contributes very little to greenhouse gas emissions,” Kahele said. “But they experience the greatest effects of not addressing climate change.”

Hawaii is already a leader in solar energy generation, and in 2015 it passed a law requiring that the state’s grid run on 100 percent renewable energy by 2045. Already, 90 percent of Kauai’s daytime energy needs are met by renewable sources. Kahele said that Hawaii should build on these gains. In particular, he wants to see more investment in innovative new renewable technologies such as ocean thermal energy conversion. Kahele supports the Green New Deal, but he’s not pollyannaish about its chances in Congress, especially if Republicans retain control of the Senate.

The Green New Deal “is a big bold idea” and “an aspirational dream,” he said. “As far as bold legislation goes, the American people have spoken and, should they decide that Republicans will maintain hold of the Senate, we need to come back to the drawing board and figure out what we can work with.”

Kansas

Representative Sharice Davids, a Democrat, is the second-ever Native American to represent Kansas in Congress. (Charles Curtis, who served in Congress from 1893 to 1907, was the first.) She believes that federal and local governments should address climate issues by focusing on public health and investing in infrastructure, such as sustainable housing. Davids has not endorsed the Green New Deal, preferring instead to hold out for legislation that might be more likely to receive bipartisan support.

A member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, Davids has said that policies like updating building codes to promote better insulation, sustainable materials, and lower energy usage are a big part of building widespread resilience in the face of the climate crisis.

“I wanted to be on that committee because transportation and infrastructure has a huge impact on climate change,” Davids said at a town hall event in March.

Oklahoma

Representatives Markwayne Mullin, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, and Tom Cole, an enrolled member of Chickasaw Nation, are two of five congressional representatives from Oklahoma. Both are Republicans who have supported President Trump’s policies. While the two now agree that climate change is real and caused by human activity, they support an “all-of-the-above” energy strategy, eliminating environmental regulations that restrict the oil and gas industry, and maintaining Trump’s withdrawal from the 2016 Paris climate agreement.

Oklahoma is home to 39 federally-recognized sovereign tribes, and Mullin’s and Cole’s constituents are already grappling numerous threats posed by climate change. Average temperatures in the Great Plains have already risen by 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit. Rainfall levels have swung wildly in recent years, oscillating between drought and flooding. The variability in water availability has hit farmers and ranchers in the state particularly hard. The 2010-2011 drought resulted in $2 billion in losses as farmers, who primarily depend on rainwater for irrigation, saw massive crop losses. According to the EPA, in the coming decades crop yields in Oklahoma are likely to decrease by 50 percent in areas where irrigated water is not available.

Despite its reputation as a major oil producer, Oklahoma has invested heavily in wind energy. The state ranked second in the country in wind energy production last year. (Texas ranked first.) Perhaps as a result, Mullin and Cole have touted the state’s renewable energy record. But the two have slightly different positions on how the industry should be supported. Mullin has said that wind energy’s success in Oklahoma shows that renewable energy can be supported by the free market alone, while Cole has supported additional investments in renewables through tax credits. (Neither Cole nor Mullin responded to Grist’s request for interviews.)

“I actually do believe that climate change is real and that humans are having an impact on it,” Cole said at a town hall event last year. “I’m all for more renewable energy resources.… I just think we need to look at different ways of addressing this problem, and we shouldn’t sacrifice our economy to try to fix it.”