You’ve read about Chris Christie, You�

Well, none of that is true when it comes to the environment.

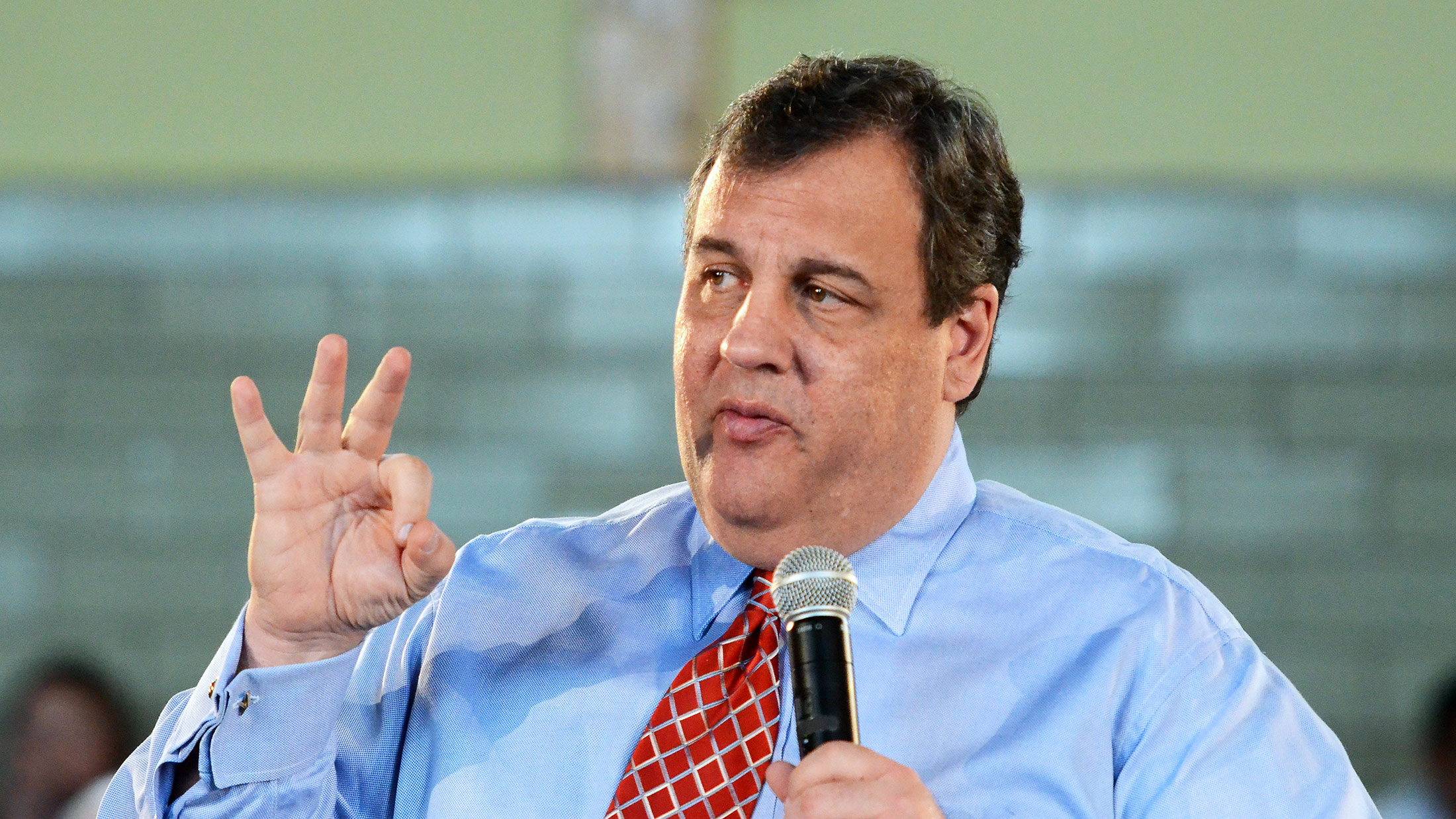

Meet the other Chris Christie, right-wing reactionary. This Chris Christie has eviscerated protections for clean water, taken rule-making authority away from nonpartisan civil servants and handed it to his political appointees, and refused to link Sandy to climate change.

“Christie on a lot of environment issues will step right in line with the Tea Party and the Koch brothers,” says Jeff Tittel, director of the New Jersey Sierra Club.

Like all movement fiscal conservatives, Christie has a zeal for deregulation of polluting industries. Upon entering office, he used executive orders to freeze and then reject environmental regulations that the state bureaucracy was in the process of making, such as a limit on the amount of chlorine in drinking water. Christie has gone on to further deregulate the chemical industry. And he vetoed a bill passed by the state legislature that would have banned dumping of fracking waste fluids in the state.

In August, he vetoed a bill to allow logging on New Jersey’s public lands — but only because he said it did not go far enough in giving the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) authority to permit logging.

In 2012, Christie gave the DEP commissioner the authority to waive almost any rule if it conflicts with granting a permit needed by another agency or private interest. In other words, if an environmental rule will cost a developer too much money, or prevent the Department of Transportation from building a highway through a sensitive wetland, DEP Commissioner Robert Martin can overrule it.

This kind of waiver authority is a national conservative fixation. “It comes out of ALEC [the American Legislative Exchange Council] but would never pass in New Jersey, so he’s doing it through regulation,” says Tittel.

Martin was appointed by Christie in 2010 after a career serving as a business consultant to energy companies and utilities, and some activism in local Republican politics. New Jersey environmental advocates say Martin was unqualified and has been hostile to the environment while in office. Martin’s deputies are also heavily drawn from the industries they regulate. In one particularly egregious example, DEP Assistant Commissioner Michele Siekerka is still serving as chairwoman of Roma Bank, which invests heavily in real estate development.

—–

The most significant challenge facing New Jersey, just like neighboring New York City, is climate change. New Jersey has a long coastline that was battered hard by Hurricane Sandy. Christie arguably owes his reelection to the storm. His image of assertive leadership in Sandy’s aftermath, his criticism of Republicans in Congress who were slow to pay for emergency relief, and his praise of President Obama’s handling of the disaster boosted his approval ratings in his Democratic-leaning state. In his victory speech Tuesday night, Christie said, “When you didn’t have a warm place for your family because of what happened in the storm, you didn’t care if it was someone who thought government should be big or small. At that moment, the ‘spirit of Sandy’ infected all of us.”

Leaving aside the fact that effective disaster relief is made possible only by big government, you would expect someone so moved by the devastating effects of extreme weather to appreciate the need for action on climate change, right? Wrong. Christie is opposed both to policies that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to preparing for the future effects of climate change on the Jersey Shore. Although Christie acknowledges the reality of climate change, he says he has “no idea” whether it increases the severity of storms such as Sandy. His policies reflect that willful ignorance.

“The biggest damage Christie has done has been on climate change, sea-level rise, and clean water,” says Tittel. “The irony is that he’s gotten this great publicity over Sandy, on which he’s considered a leader.”

In 2011, Christie withdrew New Jersey from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a cap-and-trade program for Northeastern energy utilities. Christie explained that RGGI was “nothing more than a tax on electricity,” which is a bit like complaining that Bruce Springsteen is nothing more than a rock musician.

Prior to Christie, New Jersey had an energy master plan calling for a 30 percent renewable portfolio by 2021, but Christie rolled it back to 22.5 percent.

As for whether climate change may contribute to worse or more frequent superstorms such as Sandy, Christie is equivocal, saying he has no time to ponder such “esoteric theories” and “distractions” when he is busy rebuilding.

But if you understand the growing impact of climate change on sea levels and storms, that will guide your rebuilding process. It does not guide Christie’s. Whereas neighboring states such as New York have updated zoning codes to require buildings in future flood zones to be two feet higher than the minimum required by the federal government, New Jersey has made no such adjustments. An editorial writer at New Jersey’s leading newspaper, The Star Ledger, reports, “as far as we know, the state isn’t using any of the available science on sea level rise for planning purposes.”

On urban and regional planning issues, Christie has been averse to public investment. He stopped plans to build a much-needed rail tunnel between North Jersey and Manhattan, and he is privatizing New Jersey’s parks.

Thanks to his unearned reputation for moderation and pragmatism, Christie is assumed to be more concerned about the environment than his fellow Republicans. Historically, that has often been the case among Northeastern Republican governors such as New Jersey’s Christine Todd Whitman. But Christie is much more conservative than Whitman on a whole range of issues, from abortion rights to cap-and-trade.

Christie takes a different rhetorical tack than Ted Cruz, one that is more carefully designed to appeal to moderate Northern suburbanites. But he is no moderate, especially on the environment. And his refusal to engage with the latest climate science means that New Jersey will lose several years of essential preparation for rising sea levels and extreme weather events.