Originally, the 26th international U.N. conference on climate change was supposed to be held last November. Then, COVID-19 devastated the world, killing over 4 million people and bringing the planet to a halt. The most important summit in the world for slowing the pace of global warming was postponed for over a year — the meeting is currently scheduled for this November in Glasgow, Scotland.

Now environmental groups are pushing to have the conference delayed once again — citing ongoing risks from the pandemic and an unequal distribution of vaccines. Climate Action Network, a global network of over 1,500 environmental organizations and civil society groups, released a statement on Tuesday calling for the meeting, known as “COP26,” to be put off even longer.

“With just two months to go, it is evident that a safe, inclusive and just global climate conference is impossible given the failure to support access to vaccines to millions of people in poor countries, the rising costs of travel and accommodation, and the uncertainty in the course of the Covid19 pandemic,” the group said in a statement.

It’s a hard recommendation to swallow as the consequences of climate change become impossible to ignore. Just last month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the U.N.-convened leading experts on climate science, said in a major report that some climate changes have already become “irreversible” — and that while holding global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius was still possible, it would require immediate and dramatic action. Earlier this week, a group of 230 medical journals declared that the failure of world leaders to curb rising temperatures is the “greatest threat to global public health.”

At November’s meeting in Glasgow, countries are expected to ratchet up their commitments for cutting carbon emissions, and iron out details around who should pay to help developing countries switch to clean energy and adapt to an increasingly dangerous climate.

Rachel Cleetus, the policy director for climate and energy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, which signed onto the statement, argued that the call for postponement of the conference doesn’t imply a call for postponing action. “We want action on the climate crisis,” she said. “We just cannot in good conscience push for an in-person, large gathering as the only way forward.”

Some delegates disagree. Carlos Fuller, the lead climate negotiator for the Association of Small Island States, a group of island nations particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels, said that the meeting must go ahead. “We now only have eight years to get the [nationally determined contributions] on the 1.5-degree track,” he said, referring to country commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. “We have wasted a year and three-quarters now. If we don’t have it now, we’ll have lost another year — that cuts it down to seven.”

The U.K. has been struggling to plan for a conference amid a pandemic. Most global climate conferences are Olympic-sized events — COP25, which took place in Madrid in 2019, had 27,000 attendees from over 200 countries. (The Tokyo Olympics had approximately 30,000 athletes, officials, and coaches.) Current British law requires travelers from 62 “red-list” countries, such as Chile, South Africa, and the Philippines, to undergo a 10-day hotel quarantine to enter the country, whether the travelers are vaccinated or not. The hotel quarantine currently costs over 2,200 pounds ($3,000) per person.

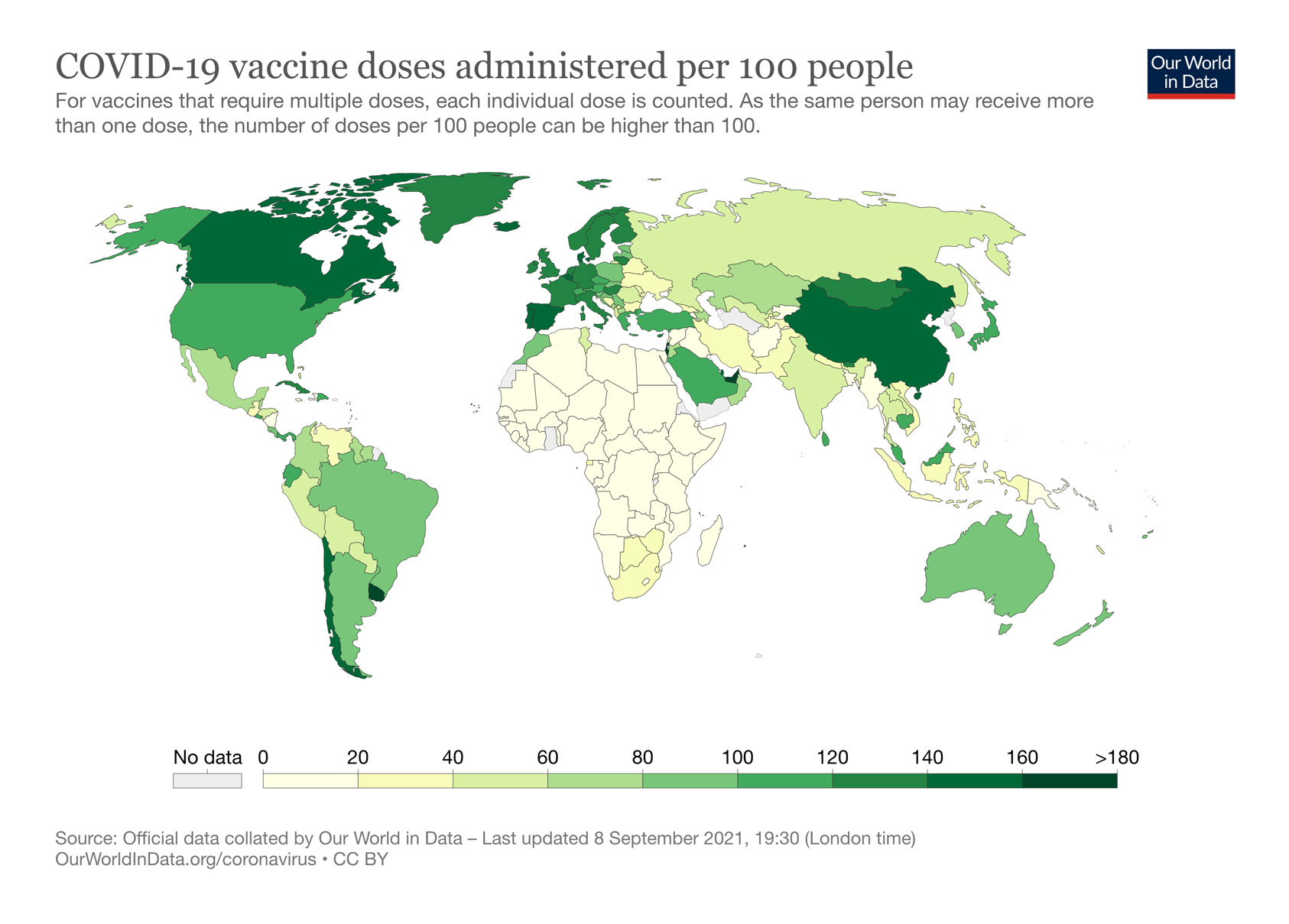

Cleetus says that the problem is twofold: Delegates from developing countries may have trouble entering Scotland for the conference and receiving timely vaccinations. U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has promised to provide vaccinations to all attendees who need them, but developing-country delegates have complained that the roll-out is moving too slowly, with less than two months to go before the conference is scheduled to start. And, Cleetus argues, there’s the broader problem of rolling out the vaccine worldwide — developing countries are lagging far behind in vaccinations compared to their developed counterparts. Many African countries, for example, have administered only 1 or 2 vaccine doses for every 100 people, compared to over 100 doses in the U.S., Canada, and many European countries. Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg has already said she will not attend the conference as a result of these inequalities.

But if environmental groups plan to wait until global vaccine equity is reached, COP26 could be on hold forever. “We are in a climate emergency and cannot wait,” Mohamed Nasheed, the president of the Maldives, said in a tweet.

Although interim meetings have been held online, Fuller explained that many nations — including those that emit the most carbon dioxide — refuse to make concrete decisions via videoconference. “We really need to go ahead and have it,” he said.

After the NGOs released their call for postponement, the U.K. government said that it planned to continue with the planned event. Organizers also promised to fund any required quarantine hotel stays for travelers from red-list countries, and said that those in developing countries who had requested vaccine access should be receiving their first dose sometime this week. “COP26 has already been postponed by one year,” said Alok Sharma, the president of the event, in a statement. “We are all too aware climate change has not taken time off.”