President Joe Biden ran on a platform that promised climate action on a scale never seen before in American politics. One of the supporting beams of that plan is something called a clean energy standard — a mandate for utilities to generate a certain amount of clean electricity by a set date. Biden’s proposed standard targeted a carbon-free electricity sector — the second-most polluting slice of the emissions pie in the U.S. behind transportation — by 2035.

Congressional Democrats sought to put that clean energy standard into Biden’s first major legislative priority — a $2 trillion infrastructure package aimed at improving the nation’s infrastructure and simultaneously reducing emissions. But a handful of centrist Republicans and Democrats succeeded in whittling down the package by about a trillion dollars and removing the standard from the bill, which has already passed the Senate and is poised for a vote in the House this week. Biden and progressives promised to get their clean energy standard done another way. That’s how something called the Clean Electricity Performance Program, a wonky and complicated climate policy that nobody had ever heard of before this month, made its way into Democrat’s $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation bill.

The CEPP, as it’s called, could be Democrats’ last best chance to pass climate policy this decade. And if it passes, it will become the nation’s first-ever federal policy aimed at significantly reducing emissions from the power sector. A year ago, the CEPP didn’t even exist as a concept. Its invention is an acrobatic feat and a calculated effort to get past arcane Senate rules.

In January, Democrats found themselves in a rare and unexpected position. Joe Biden had ousted former President Donald Trump, Democrats had hung onto a slim majority in the House, and Raphael Warnock and John Ossoff had pulled off two extremely unlikely Senate runoff races in Georgia, meaning Democrats finally had, by the skin of their teeth, a trifecta.

Environmental policy groups immediately started putting their heads together to find a way to make Biden’s clean energy standard happen without Republicans. The groups that initially led the charge — Third Way, a center-left think tank; Evergreen Action, an environmental policy outfit; and the Natural Resources Defense Council, the nonprofit environmental advocacy group — knew that there was only one pathway to success: a little-known process called budget reconciliation.

“Ever since we realized that budget reconciliation was going to be a process that we could do, conversations about how you could do a budget-based clean energy standard started up,” Lindsey Walter, deputy director for Third Way’s climate and energy program, told Grist.

Each year, the House and Senate pass budget resolutions that establish the dollar amounts that the various federal agencies, like the Department of Defense and the Department of Commerce, can spend. These resolutions are not binding, but they set the course of debate for the entire year in both chambers.

Budget reconciliation is when committees make changes to laws that have to do, exclusively, with spending, revenues, or the federal debt limit. Crucially, reconciliation is immune to the filibuster — it only takes 51 votes to pass it in the Senate. That meant that the majority party could pass a climate policy like the clean energy standard in a budget package, if all 50 Democratic senators voted for it and Vice President Kamala Harris served as a tiebreaker. But it would have to look different in order to abide by the strict rules that govern the reconciliation process.

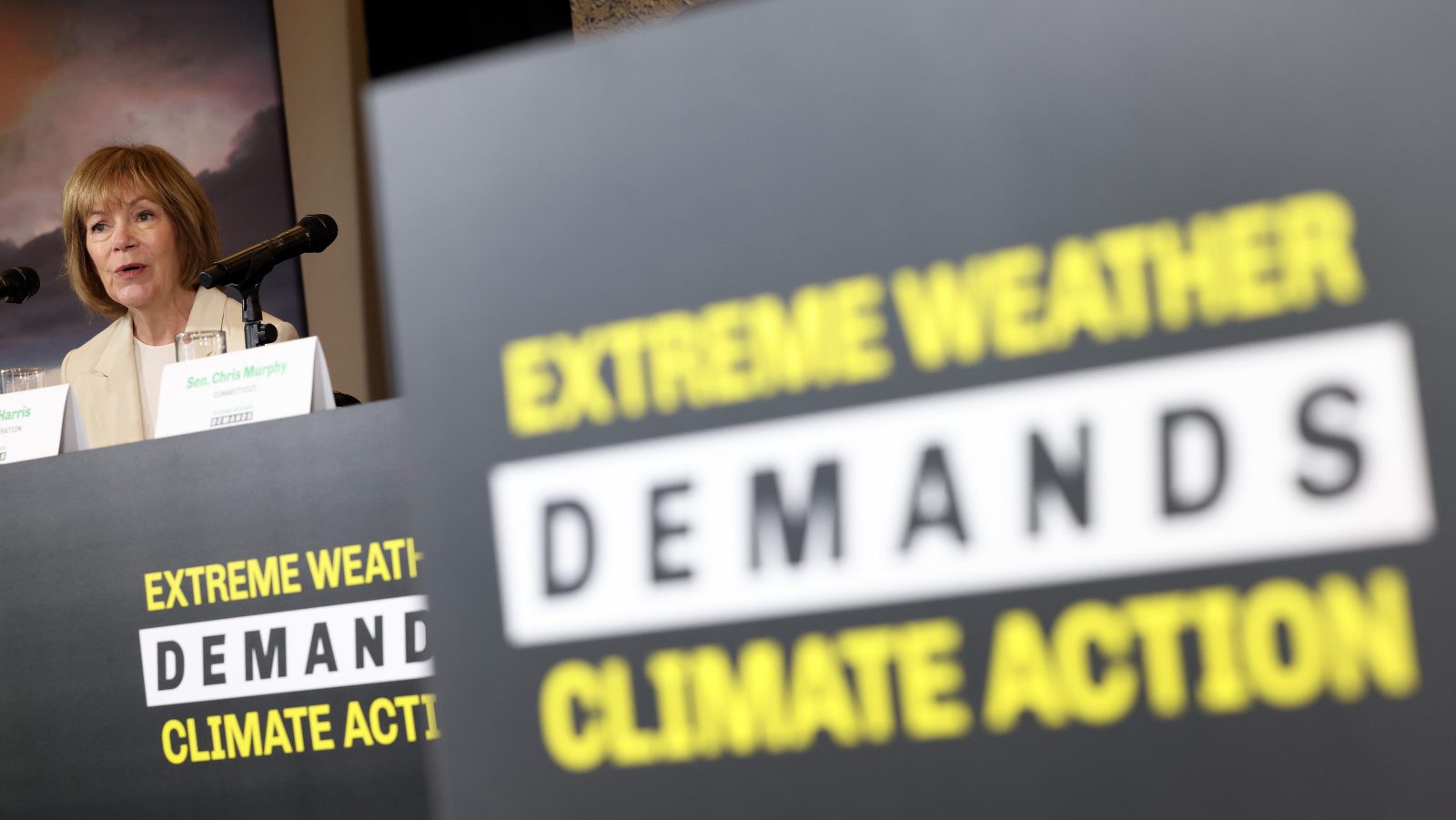

Since January 6, the day Democrats clinched the Senate, Senator Tina Smith, the junior Democratic senator from Minnesota, had also been thinking about how to make a clean energy standard fit the budget reconciliation process. She had introduced a clean energy standard bill back in 2019, a policy she knew was doomed under Trump but could get a second chance at life in the next presidential cycle. But the clean energy standard was a mandate, not a fit for the parameters of reconciliation. In order to figure out the best way to make the standard amenable to the process, Smith’s office started collaborating with the green groups, some of which had already put out policy papers on how to get a clean energy standard passed via reconciliation. Their powers combined produced the CEPP, the first federal climate policy of its kind.

“I haven’t seen a policy like this in front of Congress before,” Walter, from Third Way, said. “This would be in many ways a first.”

Here’s how the CEPP works as both a clean energy standard and a reconciliation-friendly piece of policy.

A clean energy standard is built on a foundational assumption: If utilities produce more clean power, they’ll become greener over time, and emissions will go down. But forcing utilities to get clean isn’t a budgetary matter, it’s a policy change. The CEPP gets around that by using federal dollars — which, of course, pertain to the budget — to reward utilities for going green.

More specifically, any type of company that retails electricity that increases its share of clean energy by 4 percent each year can tap into a $150 billion grant program created by the CEPP. Clean energy is defined as power sources that emit no more than 0.1 metric tons of emissions per megawatt-hour, which include wind, solar, geothermal, nuclear, and hydropower.

So if you’re a company that sells power to customers and you manage to increase the amount of clean electricity you provide to customers by 4 percent in a year-long period, you would get $150 for every megawatt-hour of clean energy you sell over 1.5 percent of the previous year’s target. And if you don’t meet that 4 percent goal, you get penalized $40 for every megawatt-hour of clean electricity you failed to come up with. Plus, you have to make up the deficit the following year. This concept, applied to utilities across the U.S., would ultimately lead to emissions reductions of about 82 percent from 2005 levels by 2030, when the program would end.

“You’ve now taken a policy idea — the clean energy standard — and turned it into a budgetary tool,” Representative Sean Casten, a Democrat from Illinois who formerly worked in clean energy development (and used to be a contributor to this magazine), told Grist. “If we’re doing it right, hopefully it has the same impact as a clean energy standard.”

Critics of the plan have argued that transitioning to a grid that mostly relies on clean energy within a decade would sacrifice reliability, a concern that has been top of mind for many since a deadly winter storm in February knocked out power for wide swaths of Texas and created a humanitarian crisis.

“Any time you make rapid changes to a system you potentially put some reliability at stake,” Rich Powell, executive director of the centrist climate and energy policy think tank ClearPath, told Grist. “I think most people who look at the Texas situation for example would say that actually if a number of the big coal plants that had recently retired in Texas had been around and available they very likely could have contributed to getting the power back on that system faster.” Powell argued that maintaining a diversity of fuel sources, pairing polluting energies like natural gas with carbon capture, and weatherizing all of them against extreme events like the Texas winter storm would be the best way to accomplish emissions reductions without sacrificing reliability.

But it’s not a foregone conclusion that a grid that relies primarily on renewables would result in a situation where there’s not enough electricity to go around. “I think that’s a bunch of hogwash, frankly,” Sam Ricketts, cofounder of Evergreen Action, told Grist. “I vehemently disagree with the assertion that this can’t be done. Utilities are already showing that the transition is possible.”

An analysis provided to Grist by Evergreen Action suggests that the CEPP would not sacrifice grid reliability. A 70 to 90 percent clean grid would be able to provide enough supply to meet demand, the analysis said. It also shows that at least 12 U.S. utilities are already on track to grow their share of clean electricity by more than 3 percent annually in the coming years. “We need to help those utilities and ensure that every utility is actually making the transition, which means faster than they’re planning to go and using federal investment to make it happen,” Ricketts said.

Casten also rejected the reliability argument. “The sun does not shine 24 hours a day and the wind does not always blow. Nobody doesn’t know that,” he said. “The question of what can you do in order to get a 100 percent zero-carbon grid just with existing technologies? There’s an infinite number of ways you could do that. We could expand nuclear. We could build out a ton of geothermal. We could invest in energy efficiency. There’s no reason you can’t technologically get there.”

The plan may be possible from a technological standpoint, but it remains to be seen whether it’ll work politically. Democratic Senators Joe Manchin from West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema from Arizona are at odds with progressives in their caucus, like Senator Bernie Sanders from Vermont, about the size, cost, and ambition of the $3.5 trillion reconciliation plan.

A spokesperson for Senator Tina Smith’s office told Grist that Smith and Manchin have been discussing the possibility of a clean energy standard for months. But there’s no saying, at this point, exactly what the powerful West Virginia Senator wants the CEPP to look like, if he agrees to vote for it at all. It’s possible that he will advocate for eliminating the penalty from the program, which would make it all carrot and no stick. He might seek to redefine what “clean” energy means — Manchin has long been an advocate of carbon capture technology, which is still relatively nascent but could, hypothetically, be added to natural gas–fired power plants to reduce emissions and fit the contours of the CEPP. Or he may refuse to vote for it altogether. Manchin has said publicly that he believes utilities are already decarbonizing on their own as renewable energy becomes more affordable. Still, Smith’s office is confident that the program will garner support from 50 senators when all is said and done.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi plans to bring the bipartisan infrastructure bill to a vote in the House on Thursday, despite promising her progressive colleagues that she would bring the infrastructure bill and the reconciliation package to the floor at the same time. The idea was to use the bipartisan deal as leverage to force the warring factions of her party to pass both bills. But on Monday, Pelosi announced that she was forging ahead with the infrastructure deal because her party hadn’t agreed on a price tag for the reconciliation bill. On Tuesday, the chair of the House Progressive Caucus, Representative Pramila Jayapal from Washington, said that progressives “will only vote for the infrastructure bill after passing the reconciliation bill.”

Depending on what happens next, the budget reconciliation bill, and the CEPP within it, could shapeshift a lot in the coming days and weeks. Casten is confident that the general structure of the CEPP will remain in the deal, but beyond that, he’s not sure about anything. “There’s more people than Joe Manchin I wouldn’t trust in a dark room with climate policy,” he said. “Until it’s written into law and signed, assume that all the text is variable.”