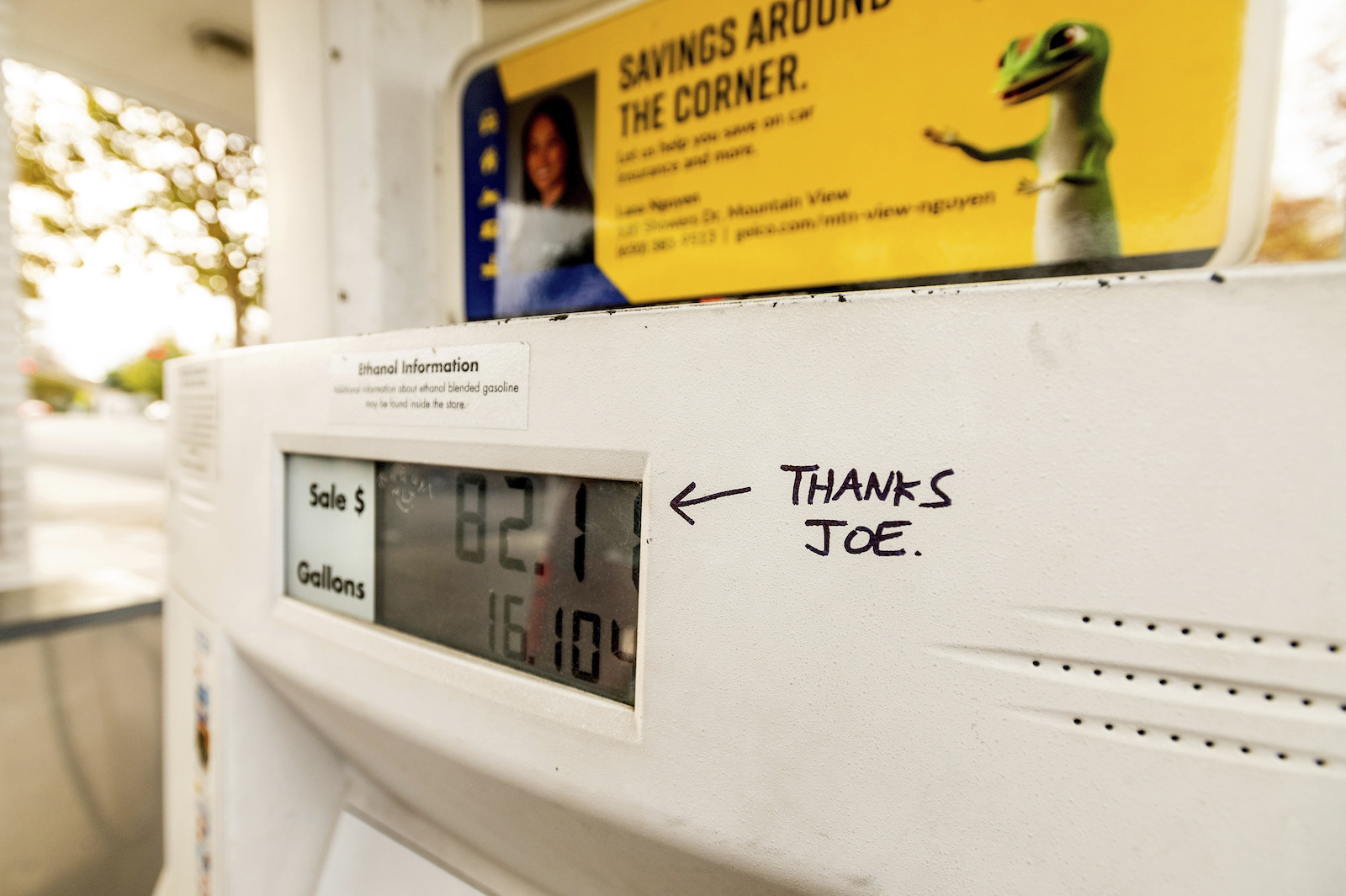

“Pain at the pump. Pain at the pump! PAIN AT THE PUMP!!!!!” This refrain, manically employed by American politicians and pundits to bemoan rising gas prices, is so common that a foreign visitor might assume that we are only allowed to fill up our cars at the gas station after first submitting to a kick in the shins.

But of course, in our hallowed American rhetoric, the most discussed pain is of the economic variety. That was apparent at this week’s State of the Union address, when President Joe Biden made sure to assuage Americans’ biggest fears about the war in Ukraine – namely, that the conflict would adversely affect their gas prices.

“Tonight, I can announce that the United States has worked with 30 other countries to release 60 million barrels of oil from reserves around the world,” Biden said. “I know the news about what’s happening can seem alarming to all Americans. But I want you to know that we are going to be OK. We are going to be OK.”

The price of a gallon of gas has increased, in increments of a few cents at a time, by about a dollar over the past year. If you were to examine the forces behind each of those increases, you would indeed find a great deal of pain of the physical and psychological variety: The widespread death and illness caused by COVID-19 that were treated as an inconvenience to production; the mounting, devastating evidence of climate change that has caused more and more investors to question the feasibility of gas companies’ business models; and now, the war in Ukraine.

And sure enough, President Biden’s State of the Union Address brought the conflict in Ukraine back to the ever-present theme of “protect[ing] American businesses and consumers.” Those who subscribe to a particular brand of optimism may have hoped to hear the president use this opportunity to propose — instead of rolling more barrels of oil out of the reserves — renewed commitment to non-fossil fuel sources of energy. But even for a so-called “climate president,” Biden’s choice to focus on how we maintain the status quo is not surprising, particularly with midterm elections looming.

If the past two years of anti-mask and anti-vax hollering have proven anything, it’s that Americans consider change very, very painful — even when the refusal to change causes real and enormous pain to others. And history has certainly demonstrated that voters will not kindly suffer a fool who threatens their God-given right to drive.

If you are still struggling to understand what war in Ukraine has to do with gas prices at home, here is an extremely simple explainer: Russia is blessed with massive oil and gas reserves, which constitute a complicated bargaining chip for President Vladimir Putin. On one hand, Russian fossil fuels provide a crucial proportion of energy for a number of European nations such as Germany, which pulls more than half of its gas needs from across the Urals. But the Russian economy is also heavily dependent on its oil and gas exports, which makes it vulnerable to sanctions.

And while world leaders have so far hesitated to impose such sanctions on oil and gas in particular, a number of private corporations such as Shell, BP, and Exxon have cut off business with Russia. To that end, oil markets have already begun to anticipate widespread rejection of Russian reserves, which all boils down to the resurgence of the aforementioned bogeyman of … high gasoline prices.

Let us turn back in time to 1979, which parallels our current moment. The violence and upheaval of the Iranian Revolution, in which the Ayatollah Khomeini took power and established an Islamic government, interrupted oil production, resulting in a reduction in the oil-rich country’s exports. But the more significant cause of the ensuing dramatic price surge, economists have said, was an ongoing growth in demand combined with oil hoarding in anticipation of further unrest in the Middle East.

Then-President Jimmy Carter preached a message of conservation to his fellow Americans. He instituted gas rations and established the Department of Energy. He famously addressed the nation in a televised address in front of a fireplace: “We must not be selfish or timid if we hope to have a decent world for our children and grandchildren,” he said. “We simply must balance our demand for energy with our rapidly shrinking resources.”

Even at present, a few days after the publication of an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, report that says we are very close to running out of time to avert truly catastrophic degrees of global warming, that seems like a shocking ask from a sitting president. In 1979, it was especially unwelcome. Arguably as a result of the ensuing gas shortage, President Carter was not reelected, and his successor Ronald Reagan campaigned on a message that “‘less’ is not enough,” while singing the praises of deregulating the American oil industry.

In June 2008, the price of a gallon of gas hit an all-time high point in American history: just north of an average of $4 a gallon, which would be about $5.22 today. President George W. Bush addressed the nation on the topic, noting that “for many Americans, there is no more pressing concern than the price of gasoline.” After some tsk-tsking of the Democrats in Congress for their role in the “painful levels” of gas prices, President Bush went on to give a rousing argument for accelerated, deregulated domestic oil and gas production that included, among other things, a hearty defense for drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

The climate consequences of increased oil and gas consumption were already well underway. At the very moment that Bush addressed the nation on the need for more drilling, a swath of the Midwest was underwater due to a 24-day period of torrential rains. The disastrous flooding was concentrated primarily in Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri and killed 11 people, the majority of whom died in their cars. In a postmortem study of the unusual hydroclimatological circumstances that created floods, researchers with the American Geophysical Union wrote: “The occurrence of the 2008 flood event raises the question of whether its occurrence provides further evidence for a changing character of Midwestern hydroclimatology due to anthropogenic influences.”

But it was, again, gas prices that would prove a more pressing issue. In the spring of 2011, the price of gasoline shot up again, very nearly reaching the $4-per-gallon mark, and it would hover around $3.75 for the next three years. In President Barack Obama’s 2013 State of the Union Address, he sang the praises of the burgeoning shale gas boom that “has led to cleaner power and greater energy independence,” which he considered a motivation for his administration to “keep cutting red tape and speeding up new oil and gas permits.” He expressed a commitment to “free our families and businesses from the painful spikes in gas prices we’ve put up with for far too long.”

In that same speech, Obama did briefly mention that we “must do more to combat climate change,” and that the slew of natural disasters plaguing the country should not be considered a coincidence. Hurricane Sandy, which had torn across the Atlantic Coast a little more than three months earlier, killed upwards of 200 people in the United States and in the Caribbean. Those deaths, and any injury, distress, and trauma experienced by the people who survived, went unacknowledged.

And now, here we are. President Biden closed his 2022 State of the Union address — which included no mention of the IPCC report — with a message that one assumes was intended to be inspiring, but is difficult to hear without mercenary connotations: “We are the only nation on Earth that has always turned every crisis we have faced into an opportunity.”

That opportunity has already seized the attention of West Virginia Democratic Senator Joe Manchin, who has received more donations from the oil and gas sector than any other member of Congress. He insisted that we sanction Russia’s oil and gas and ramp up our own domestic production, “strengthening our ability to use energy to fight for our values.”