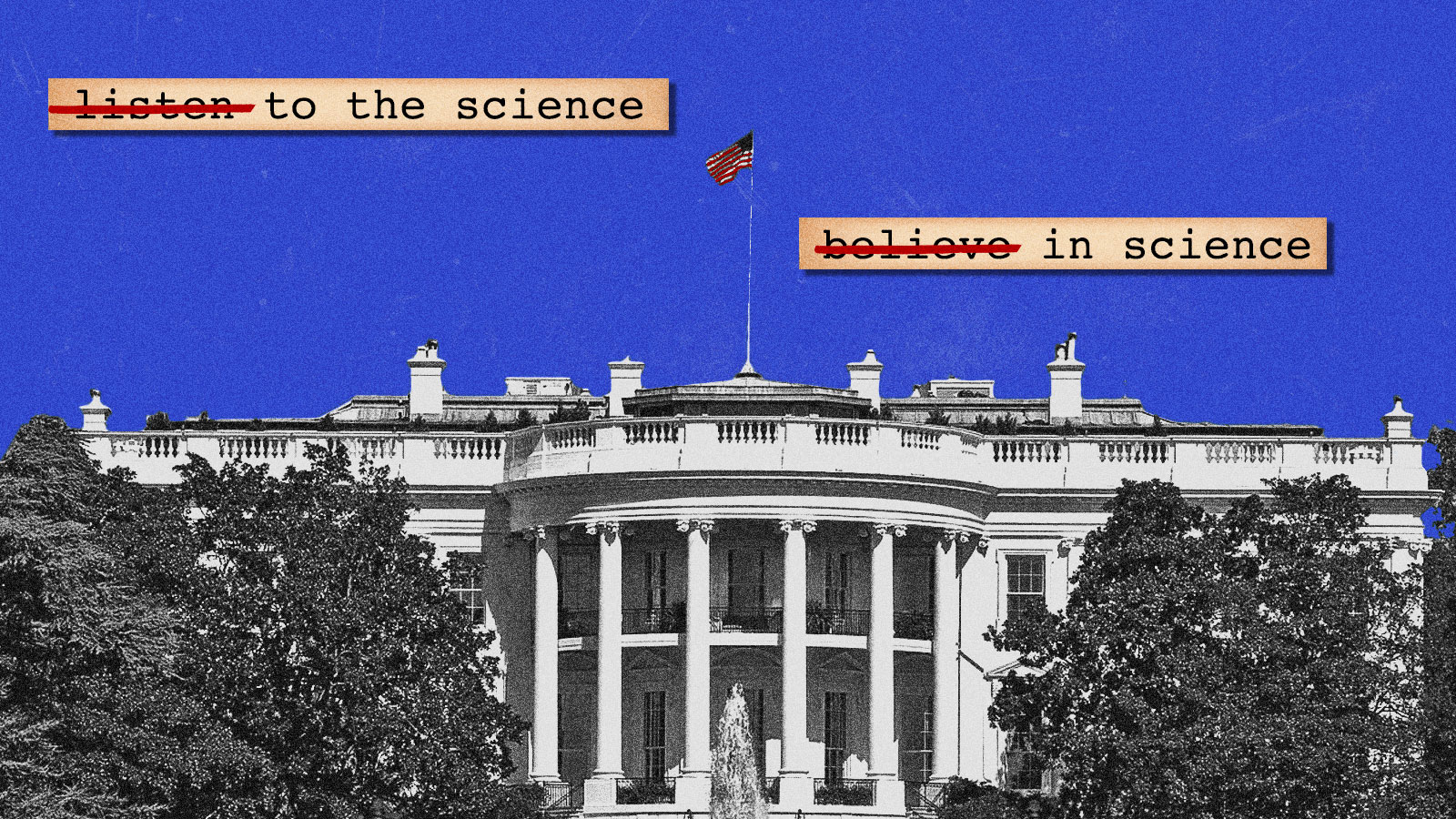

“Listen to the science” isn’t just a bumper sticker anymore — it’s official White House policy.

Flanked by a painting of Benjamin Franklin and a 332-gram sample of moon rock, Joe Biden spent his first day as president signing his name on a towering stack of science-forward executive orders: rejoining the Paris climate agreement, revoking the Keystone XL pipeline permit, and launching a review of the Trump administration’s decisions around public lands, methane emissions, and fuel economy standards for cars and trucks. He called for the federal government to “advance environmental justice” and “be guided by the best science,” as a guiding principle for tackling climate change.

“It is, therefore, the policy of my Administration to listen to the science,” he wrote in one executive order.

That all may seem like overkill, but it’s been a weird few years for science. The Trump administration censored scientists, impeded climate research, and dismissed public health officials’ advice at the height of a global pandemic. On the campaign trail, Biden often said “I believe in science” to contrast himself with his opponent, who denied the threats posed by climate change and the coronavirus pandemic but readily embraced conspiracy theories.

But according to polling from the Shelton Group, a marketing agency focused on energy and the environment, from last May, Americans still trust scientists more than almost any group outside of friends and family. That survey showed that more people trusted scientists even more than books, churches, or the school system — and far more than the press, big companies, or Congress.

So how, then, did science get so polarizing? In the eyes of many Americans, it has to do with the annoying way non-scientists talk about science. “Every time we say, ‘Well, I believe in the science,’ I think we come off holier than thou,” said Suzanne Shelton, CEO of the Shelton Group. “Really what we’re saying is, ‘Well, I believe in the science, dumbass!’”

A woman holds a pro-science sign up to a small group of pro-Trump counter-protesters during a March for Science in Los Angeles, California. Sarah Morris / Getty Images

The climate movement has long assumed that the overwhelming evidence behind climate change will convince people to care about the ailing planet and motivate them to take action. If those facts fit your worldview — and for plenty of people, they do — that works great. But when the evidence doesn’t fit into people’s preconceived notions of how the world works, they find ways to challenge or dismiss evidence that contradicts their beliefs. Evidence just bounces right off them.

“We need to get away from the idea that logic and rationality is always the most persuasive argument,” said Hollie Smith, an assistant professor of science and environmental communication at the University of Oregon. Hearing a message that’s counter to your beliefs can even result in what’s called a “boomerang effect” — when an attempt to persuade someone ends up doing the opposite.

And there’s another problem: Not only do experts say that catchphrases like “believe in science” and “listen to the science” are making matters worse, they’re also kind of, well, anti-science.

“Anytime you say a sentence with that word in it, it’s probably false,” said Sheila Jasanoff, a professor of science and technology studies at the Harvard Kennedy School. Academics have spent more than half a century researching what people even mean by invoking this thing called “science,” she said. Consider what climate science is: an amalgam of disciplines and knowledge that has been pieced together to come to a conclusion about the planet. It’s too big to see from a single perspective; Jasanoff compares scientific “truth” to a jigsaw puzzle or a patchwork, something that creates a fuller picture only when you add up all of its parts. The world is getting hotter and weirder, and lots of different signals point to that conclusion. But each piece taken individually might not display the same story.

All of this complexity gets glossed over when people use quippy phrases like “believe the science,” Jasanoff said. “The simplification of the message is itself an anti-scientific move, because it denies the actual network complexity of knowledge and of society.”

Science, after all, “says” a lot of different things — and as new data points on a topic emerge, some conclusions can shift over time. You read a headline that says red meat is bad for you, for example, and then next day, another headline says that’s bad advice. Those interpretations aren’t necessarily a problem from a scientific perspective — yay, more evidence to consider! — but when every surprising paper gets portrayed as an equally valid twist, people are bound to have questions about what it means to “listen to science.”

That’s not to say experts don’t have anything definitive to say on the topic of climate change. Science may not be a monolith, but neither is it an opinion free-for-all. “It’s horrifying that we’re in a world where some people can just lie with impunity and get away with it, and some people can just ignore facts and get away with it,” said Adam Rome, an environmental historian at the University at Buffalo. “But the answer isn’t to say, ‘We believe in science!’ The answer is to fight for the values and the visions you have.”

Academic articles have been critiquing this “science says” rhetoric for decades, said Darrick Evensen, an assistant professor of environmental politics at the University of Edinburgh. The word “scientized” has been used to describe the idea of making a claim “seem like it’s just about science” when it’s actually about complicated policy issues and moral and cultural questions. Science alone can’t tell us whether the United States needs a green jobs guarantee, a carbon tax, or warning labels on gas pumps.

When Biden says he “listens” to science, he might be trying to say that he’s using peer-reviewed, authoritative, and fact-checked sources, Evensen said. But the phrase can be dangerous because it “makes it seem like there’s no value judgments to be made,” he said. “The science describes what the situation is, what might happen … but it still doesn’t tell us what we should do. It’s our values and the things that we care about that tell us what we should do.”

Science, however, cannot be untangled from culture and politics. For example, when the National Science Foundation reviews research proposals, one of its criteria is “broader impacts” — in other words, how the research could benefit society. “You cannot say science is disinterested and sits apart from politics and policy,” Jasanoff said, adding that it can invite backlash when people discover that scientists aren’t detached and disinterested, but instead hoping to improve the world with their work. Biden, she noted, is the first president to appoint a deputy director for science and society, Alondra Nelson, a sociologist who has studied racism in medicine and the effects of emerging technology. It’s a step toward acknowledging “the reality of the way that science does interface with society,” Jasanoff said.

Society also doesn’t benefit when people with questions about science get shut down too quickly, Jasanoff warns. The public has understandable concerns, “whether it’s mothers, fearful for their fragile children’s health, who will not tolerate a vaccine, or communities that are dependent on fossil fuel extraction who don’t know what will happen to them if the fossil fuel industry shuts down.”

If people are hesitant about getting a COVID-19 vaccine, Heidi Larson, the director of the Vaccine Confidence Project, told NPR, the “most important thing” is to hear them out. “I think that one of the reasons that I see that the anti- and questioning and skeptical voices have gotten louder is they feel like they’ve been shut down when they tried to express a concern or have their view,” Larson said. “And it has kind of hardened the views because people feel cut out.”

If you’re actually trying to convince someone, put down the “pro-science” megaphone and try to understand where they’re coming from. Then work to find common ground. “I wish we would stop arguing so much about science, because I think it is polarizing. And I wish we would focus on our kids, because that’s not polarizing,” said Shelton, the marketing CEO. She recommends targeting messages for the type of person you’re trying to reach: Future-oriented messages tend to work for progressives, for example, but nostalgic messages are more effective for conservatives. (There’s a reason that “Make America Great Again” resonated with many Americans.) That might mean talking about the glory days of sledding in cold, snowy winters and the fun afternoons you spent fishing with your grandpa versus quoting the latest U.N. climate report.

At the end of the day, Americans would benefit from a more nuanced way of talking about science — and talking to each other. The way science gets talked about now, “You’re either for science, or you’re an ignoramus and deplorable,” Jasanoff said. “And we know that has had corrosive, corrosive impacts in the American polity that are not matched anywhere else in the world.”