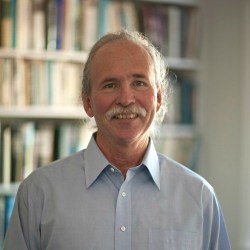

Richard White. (Photo by Jesse White.)

You know the feeling: the intoxicatingly fresh air, the crunch of leaves under your hiking boots, and only the chirps, gurgles, and caws of the forest to keep you company as you wander down the trail. Ah, to be free of people and surrounded by untouched nature …

Environmental historian Richard White will stop you right there. This contrast between a hike in the woods and a walk down the city streets, between Yosemite and your office cubicle, is not one of nature versus non-nature. People have lived in, worked in, and even burned these landscapes throughout history, White says, and the idea of pristine wilderness that is “untrammeled by man” — or so goes the Wilderness Act — is a myth. “Particularly with climate change,” he says, “we have now touched everything except maybe some of the deepest parts of the ocean.”

A 2012 Pulitzer finalist for his book Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America, a recipient of a 1995 MacArthur “Genius” award, and presently the Margaret Byron Professor of History at Stanford University, White makes a living sifting through the trash bin of the past. He strings together facts that often compete with the stories we tell about ourselves, and about our Earth. Removing human impacts from the land today, he argues, is the most “unnatural” thing we could do.

Yeah, OK … but wait. How can humans be a natural part of the earth system when we have nuclear bombs? When we hydraulically fracture the earth, pump carbon into the atmosphere, and extract bitumen from tar-sands fields? In this conversation with Richard White, we will consider the changing relationship between people and the environment, and what this means for the future of humanity and the planet.

Free MP3. (Right click, select “Save Link As.”)

This interview is part of the Generation Anthropocene project, in which Stanford students partake in an inter-generational dialogue with scholars about living in an age when humans have become a major force shaping our world.